JF Ptak Sciene Books Post 1906

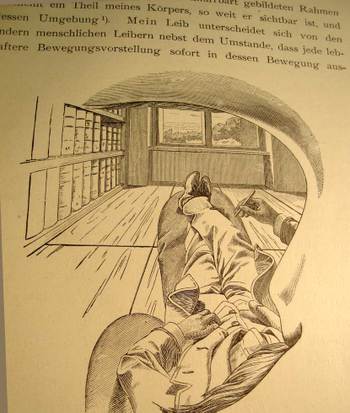

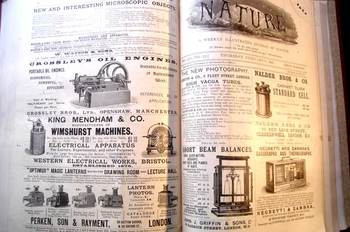

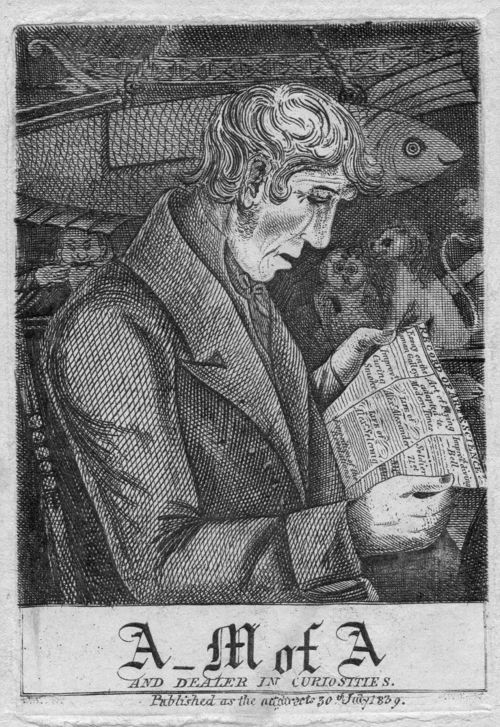

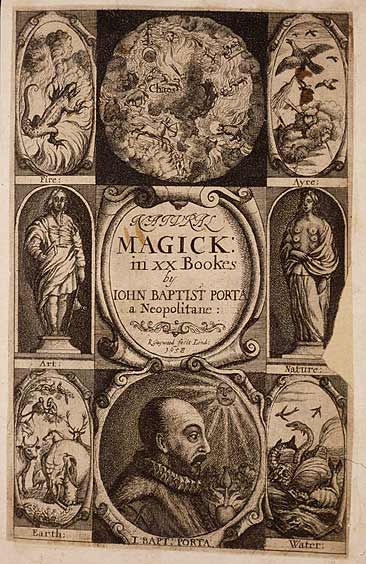

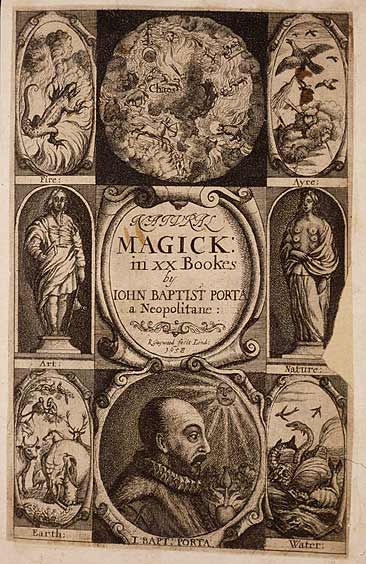

[Detail from the title page of Natural Magic, below.]

Giovani Baptista della Porta was a magus, or a natural (science)

"magician", who searched nature for similarities that would serve to build a

broad template of forced understanding of seeming likenesses, looking for the great connector

in the exceptional and the unusual, the stuff outside of the formerly

Aristotlean world. Natural Magic is his magnum opus, an expansion of its earlier

version (Magna naturalis) published in Latin in 1558, which Porta expanded to twenty sections in 1589. The 1589 edition was a maturing of the 1558 edition, toning down the philosophical/religio-mystic basis for the ordering of the natural environment with an approach more suitable to observation and experimentation. It was an encyclopedic work of vast proportions, a

gold-mine of information and clever wishfulness, and very accessible due to

Porta’s wide inter-personal travel,

very wide reading and critical abilities, clear reasoning and deep vision: the book was hugely successful, going into at

least twelve Latin, four Italian, seven French, two German, and two English

editions in the early modern era. Natural

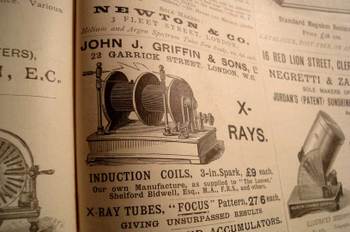

Magic, which first appeared in English in 1658, concerned itself with

magic, alchemy, optics, geometry, cryptography, magnetism, agriculture, the art

of memory, munitions, and many other topics, all grouped together and refined,

distilled, into a cloudy assemblage of natural knowledge—it would end up that the magical

whole was worth far less than the sum of its parts.

But the parts were pretty considerable, and much of the

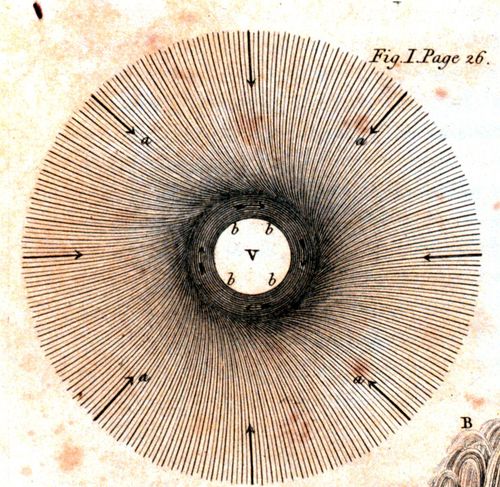

information was spot-on for the time, not the least of which was a very capable

demonstration and explanation of a lensed camera obscura.

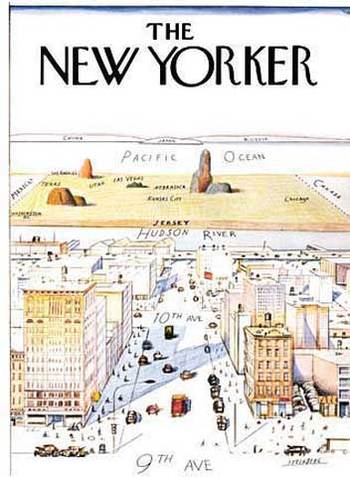

What I’m interested in right now though is the title page of

the book (pictured above).

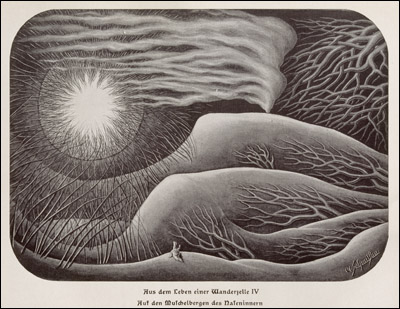

It turns out and as we can see in the top image of the

title page, Chaos is not some subspace trajectory of cellular automata, or in

Dr. Brown’s/Einstein’s dancing dust—it is right above us. This recognition of its regular, localizable structure

probably does not support parameterization, or anything else for that matter,

except to say that it is definitely “pretty”.

The title page has nine illustrated compartments: the four corners depict the four elements,

the two opposing middles show art and nature; the bottom shows the author,

illuminated by the knowing sun. The top

center image is the element showing “chaos”, which I’ve chosen to use a map,

identifying where exactly chaos might be.

I’ve not seen an antiquarian map identifying chaos, though I have seen a

number showing lots of other non-existent places, like heaven and hell and

purgatory and Eden and the Kingdom of Prester John, to name a few. But not chaos.

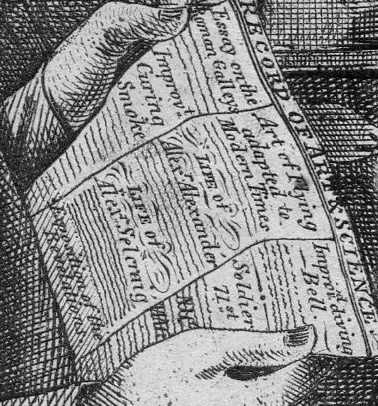

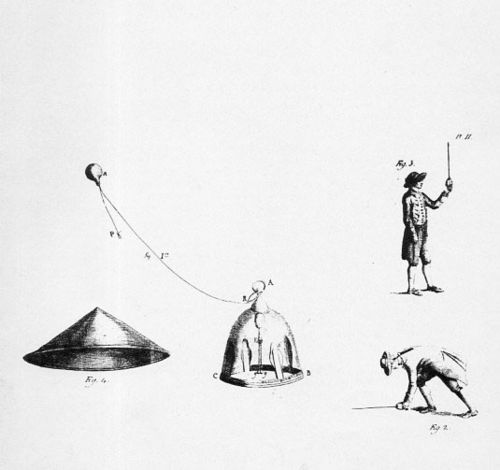

It is very interesting to note that while in the process of looking at nature, and observing connections real and imagined, and creating ways of organizing and storing information in the brain, Porta conceived of a telescope, and this several decades in advance of Galileo. (The idea of the telescope stretches pretty far back, though. The idea seems ancient, though the scientific thought on the matter really weren't present until the 13th century with the work of Roger Bacon and Robert Grosseteste, and then with Nicolsa of Cusa (in 1451) doing experimental work on the properties of lenses, and then on to John Dee and Thomas Digges in 1570/1. Porta seemed right about there, just ont he edge of the invention of an instrument which would have allowed him to see farther and deeper than anyone else before him, but he didn't follow through. He mentions in the 1589 edition of Magiae:

"With a Concave lens you shall see small things afar off very clearly. With a Convex lens, things nearer to be greater, but more obscurely. If you know how to fit them both together, you shall see both things afar off, and things near hand, both greater..." (Porta would expand this section of the 1589 book (section XVII) into a complete and separate work in 1593, De refractione optices.)

I do not know what happened to this idea, or why it didn't flourish in Porta's hand like it would in those of Galileo less than three decades latter.

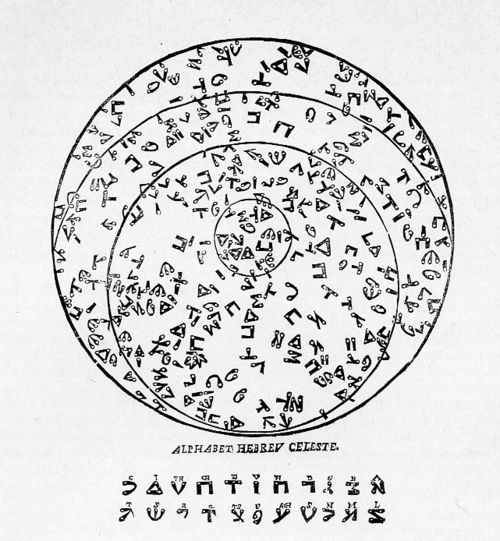

Porta was a very nimble and penetrating man--his Magia naturalis was a dissecting tool for the complexities that he saw around him, and his later works were in some ways continuations on this theme. The first two books following Magiae were concerned with private visions of Very Large Things: the first, De furtivis literarum notis (published in 1563) was one of the earliest works on cryptology. This looking-deeper book was followed three years later in 1566 by a book on how these thoughts could be organized in the mind. Given the spirit of the times and the difficulty of actually recording what it was you saw, Porta wrote Arte del ricordare, which addressed the very idea of memory and then the more applicable bits of mnemonic devices. He looked for more hidden messages in his next work--on the physiology of hands--but it didn't see the light of publishing day until after Porta died.

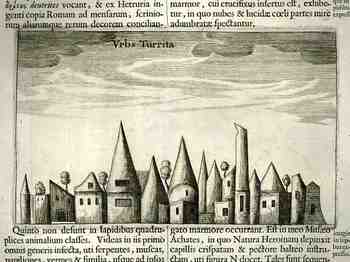

Working in the areas of pharmacology, hydraulics, military engineering, physiology, and physics, among many other areas, Porta published De aeris transmutanionbus (1609) on meteorology; De distillatione (1610), on chemistry; Coelestis Physiogranonia (1603), on a sort of "writing in the sky" and both a blast and support of astrology; and De humana physiognomonia libri IIII (1586), which was a work physiognomy and discerning function from structure. There were other books, not to mention at least 17 dramatic works. Porta was basically unstoppable.

All of this takes me back to the question of wondering about his inability (?) to see the possibilities of the telescope. In all of his books on deterministic vision, and of seeing things deeply--whether it was in the sky, or in chemical experiments, or in seeing the structure of a plant incised with its function in nature, or in the complexities of memory, and so on--it is a mystery to me how he could have left the development of the telescope along.

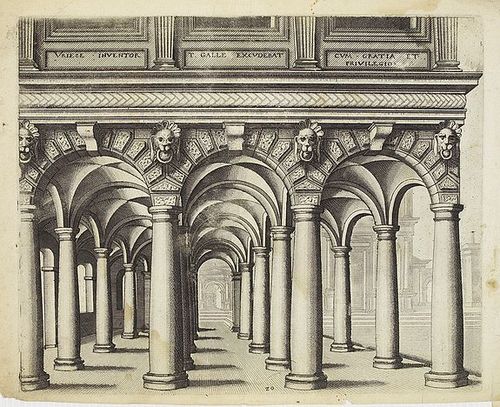

[Source: Swaen.com]

[Source: Swaen.com]