JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 788 Blog Bookstore

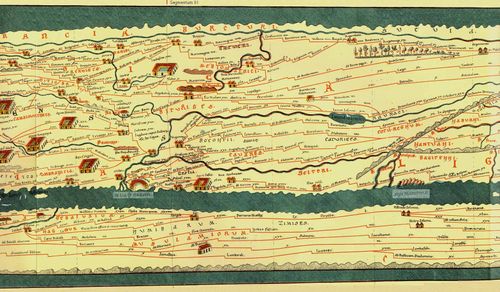

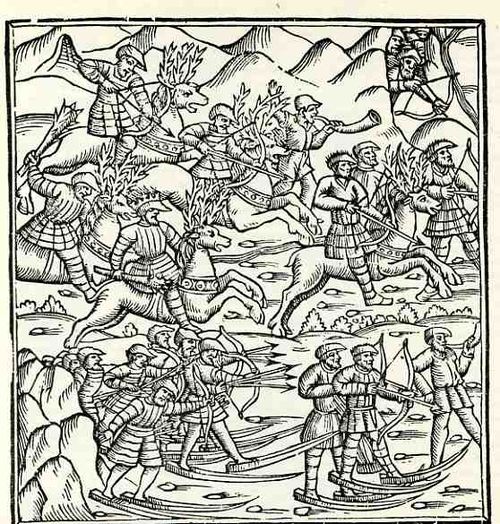

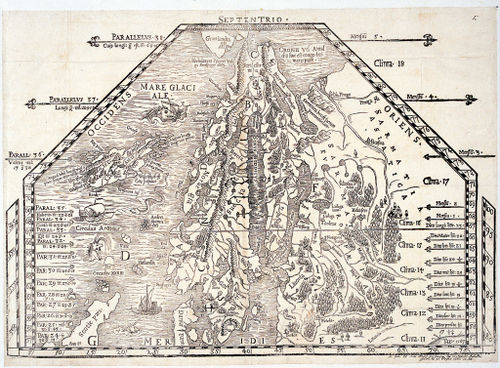

It is sobering to look at the work of the early cartographers and see how much space in their maps they were willing to relinquish to the blank unknown. For example, Jacobus Ziegler, in his Quae intus continentur

The western half of the map, featuring Sweden, Norway, Finland, Lapland and Greenland, is spectacular, and features an enormous, flat-detail, straight-edged Greenland as the bulky land mass in the west ("ulte Gron/rio/lan", a terra incognita). The extremely angular Greenland coastline stands in sharp contrast to the lovely wavy ocean, the mapmaker unafraid to stake his claim in what he didn't know.

The eastern half of the map, Scandanavia, is more recognizable (if you focus on Denmark and Germany in the south and then work your way north):

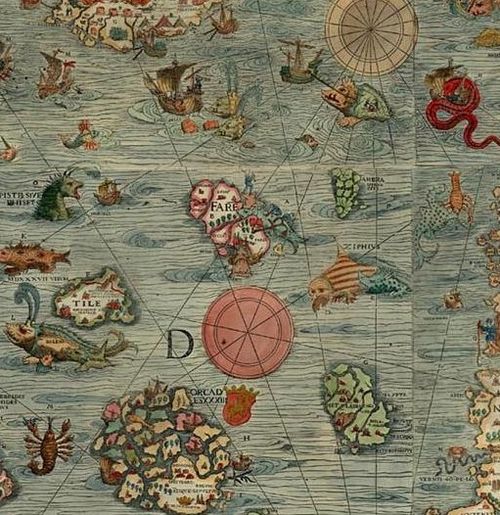

Though the unencumbered line, far from the fractal nature of Mandelbrot's coastline of Britain, appeared everywhere in the eight maps of Ziegler's work, as we can see in this intestinal-appearing Dead Sea (below). The fact of the matter is that this was the state of the art in the first third of the 16th century, and there was in general not a great effort to embellish guesses and gloss over the areas where there was no information. Of course there was still mythical placements of beings and locales and willing things into existence (like Prester John, sea monsters, El Dorado, no-headed men of South America, Patagonian giants, monsters, and so on), but I still find it remarkable to see how much rigor was given known geographic detail.

The Nile too received this unrelenting treatment of calm appraisal:

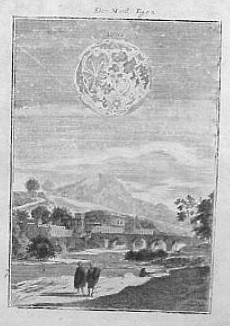

I do admire this effort for not making things up, or covering areas for which there wasn't good data with ephemeral and unnecessary features that would swallow up large swaths of white, empty space, as in this map of the lands eastern Syria:

Though there were still no problems including sea serpents, even so close to the Syrian coast:

On the whole though Ziegler's stylized effort is quite beautiful and truthful, and I enjoy the depiction of the sea giving way to the chunky, rectangulariness of even such decently known forms such as Cyprus.

The bottom line here is that folks seeing this work for the first time in 1532 would have had a similar reaction to it as you had when you zoomed in on your house in Google Earth for the first time--it was an extraordinary display of information for the time.