JF Ptak Science Books Post 1123

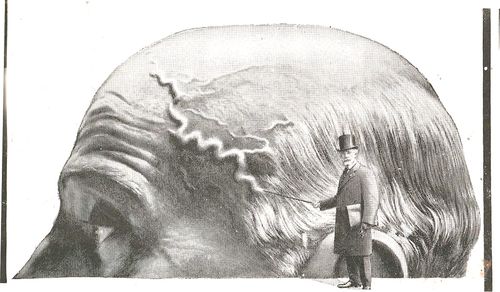

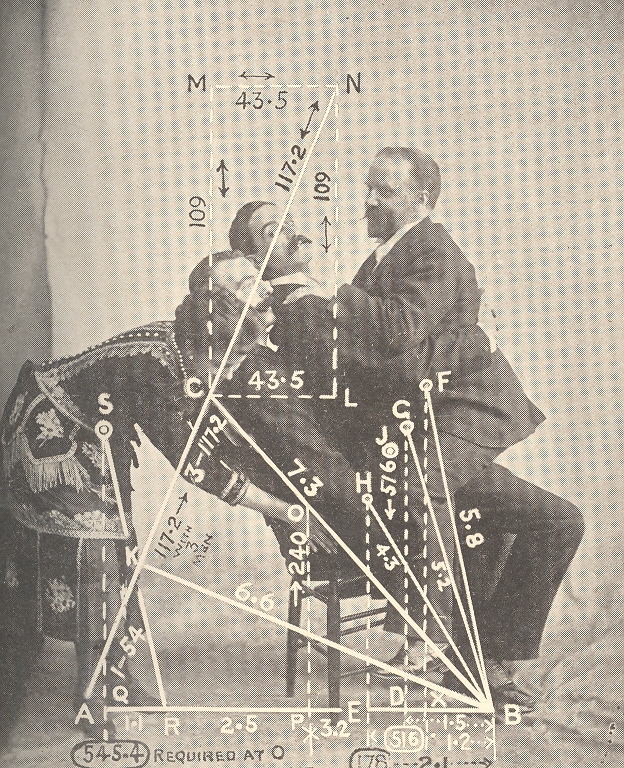

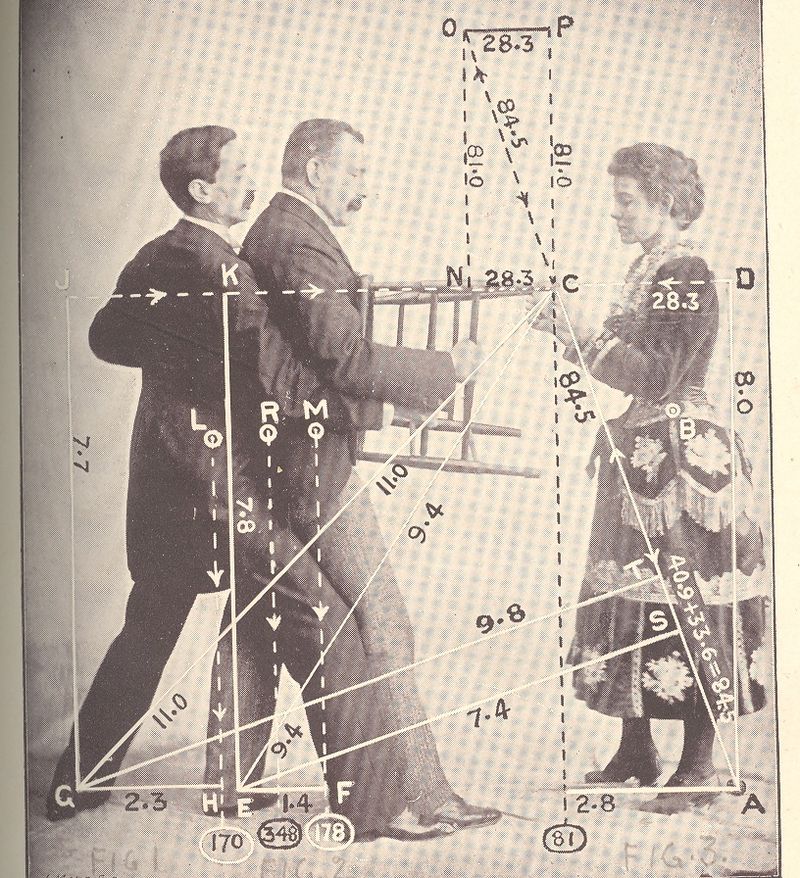

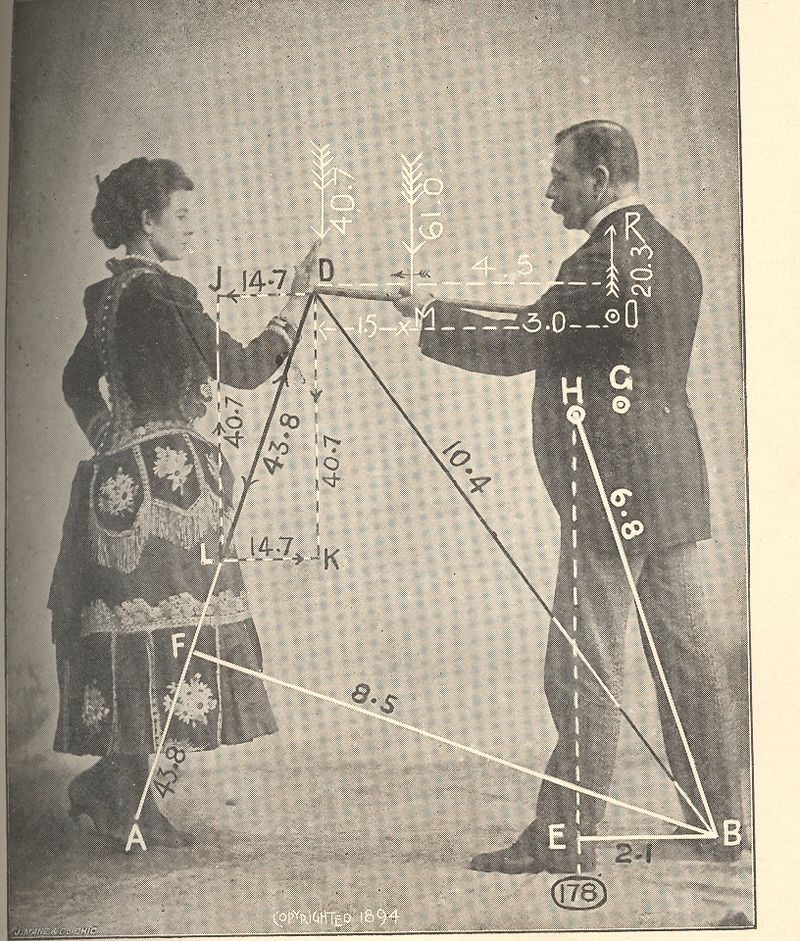

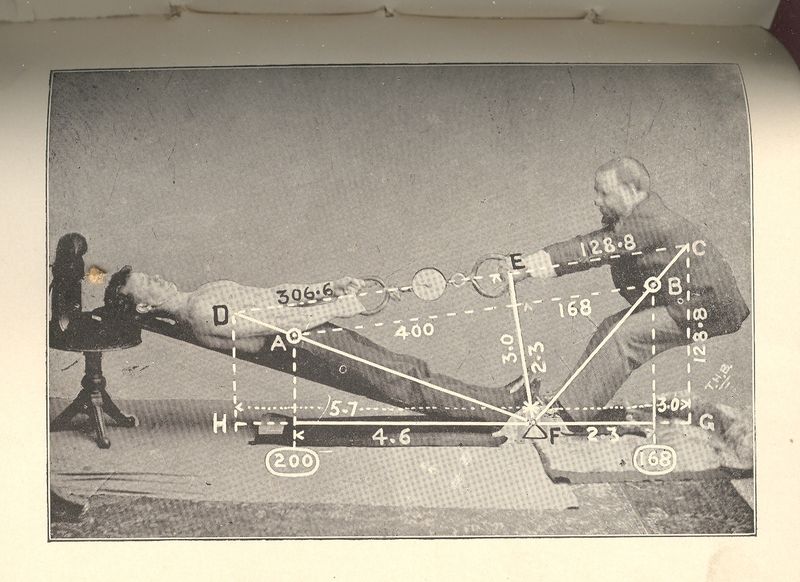

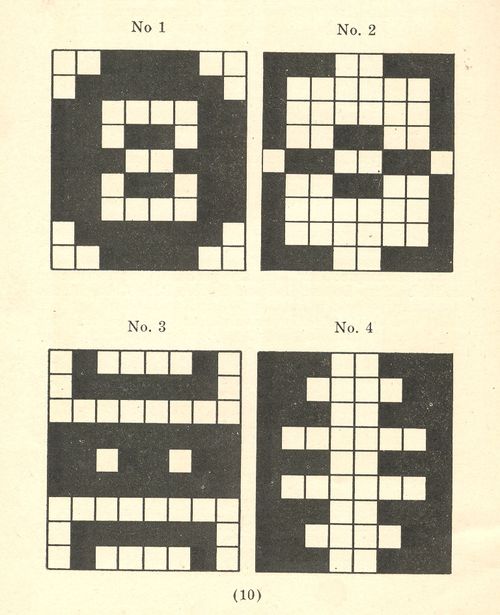

The history of mapping the goods and ills, the past and present and the future on the human body must be about as old as writing, or older. Ever since you could draw geometric proofs in the sand people have been mapping out the connections (or lack of) the parts of the human body, their relations to one another, the influences of the stars on them, the control of dermatological deformities on the health of the system, the lump and pits and dings on the cranium as an indicator of intelligence and prospects for the future, connecting the lines of electroshock results on facial contortions with the inner musings of the criminal brain, and on and on. What brings my attention to this though are the overall full-body indexes, the general NYC subway map-like overlays on the entire body, and what they look like out of context.

For my purposes here, it really is just the out of context element, the found art, the pre-Absurdist, pre-Dadaist images that they maps create. Granted the real stuff behind these images are by far more interesting, but I wanted to add these pictures to the blog's alternative art category before their Duchampian attraction left me.

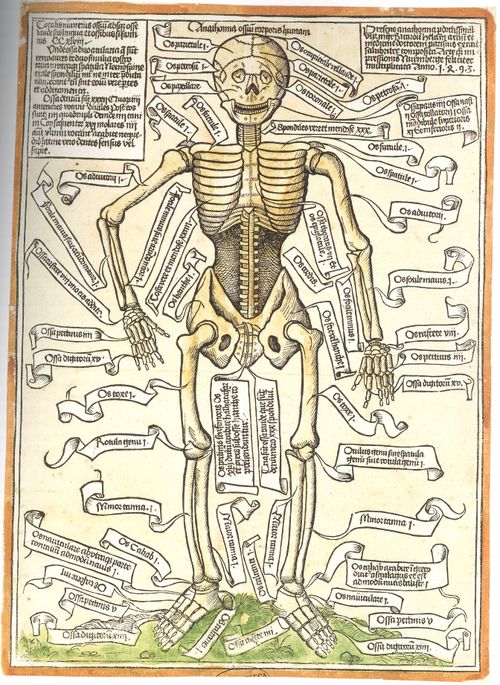

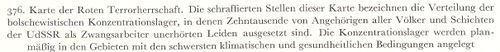

To start with, for example, in this very breezy survey is the indexing of the very first illustration of a human skeleton. from Anathomia ossium corporis humani, printed the year after Columbus arrived in the Americas--this was the first revelation to the real world of science following a sleepytime of about 8oo years under the very heavy gaze of institutional religions.

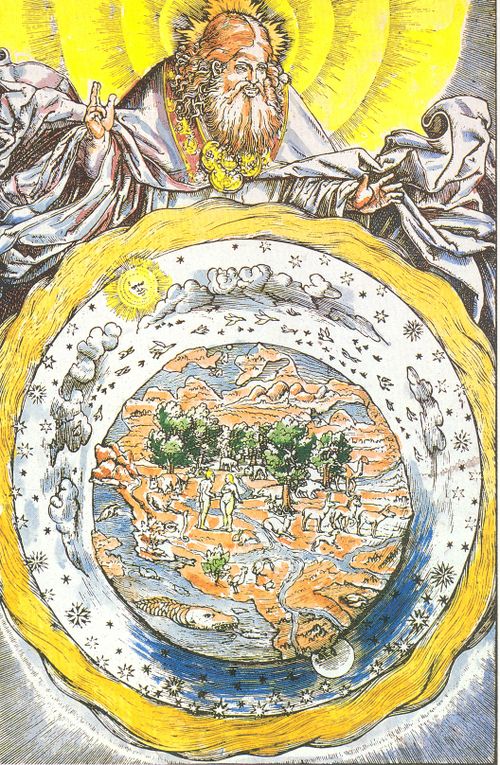

In the same year that Columbus set sail for India came the anatomical publication of John de Ketham, with his overall map of astrological influences on the body, followed by a pretty-useful treatise on the treatment of war wounds, as well as the decidedly less-useful map of his locations for the best place to bleed a person of their bad humours.

In the same year that Columbus set sail for India came the anatomical publication of John de Ketham, with his overall map of astrological influences on the body, followed by a pretty-useful treatise on the treatment of war wounds, as well as the decidedly less-useful map of his locations for the best place to bleed a person of their bad humours.

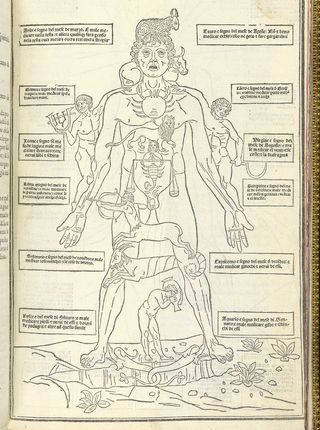

Well, it really wasn’t like that, not how I mean by by snippy modernist viewpoint looking back on medical history with no contextual appreciation. Bloodletting was an approach to healthfulness, as blood was seen as one of the four major elements (or “humours”) of the human body that needed to be kept in balance. This was

accomplished via the application of leeches or by the more common (and quicker) practice of venesection, or opening a vein to allow the blood to come out. (Let’s reference Steve Reich’s magnificent “Bruise Blood” creation of 1966 at this point—I don’t think that I’ll ever have a better chance to drop a reference to this piece of revolutionary music in regards to venesection again.) Thus this map was map for the practiconers of bloodletting—the physicians, and more probably the barbers and other assistants who would inherit this lesser procedure from the more-busy doctors. In the history of maps of anatomy and the general practice of mapping the human condition, this woodcut x-ray of the best places to drain human blood would not survive close to the age of modernity, disappearing almost entirely by the 18th century, and becoming much more scarce well before that.

accomplished via the application of leeches or by the more common (and quicker) practice of venesection, or opening a vein to allow the blood to come out. (Let’s reference Steve Reich’s magnificent “Bruise Blood” creation of 1966 at this point—I don’t think that I’ll ever have a better chance to drop a reference to this piece of revolutionary music in regards to venesection again.) Thus this map was map for the practiconers of bloodletting—the physicians, and more probably the barbers and other assistants who would inherit this lesser procedure from the more-busy doctors. In the history of maps of anatomy and the general practice of mapping the human condition, this woodcut x-ray of the best places to drain human blood would not survive close to the age of modernity, disappearing almost entirely by the 18th century, and becoming much more scarce well before that.

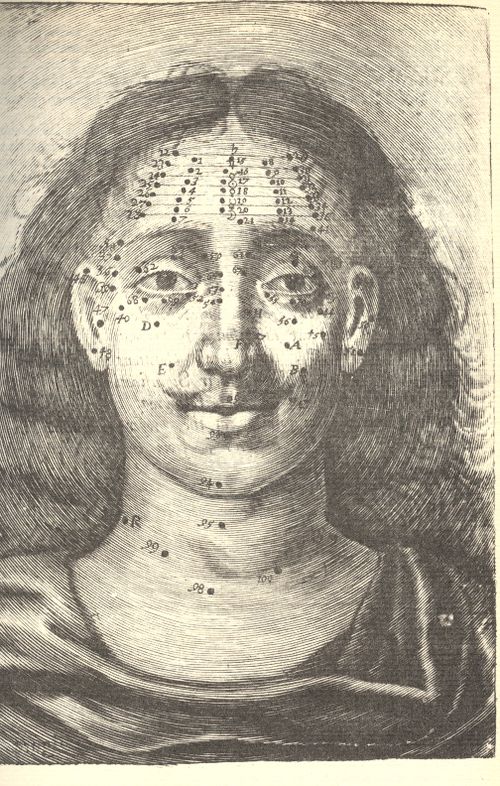

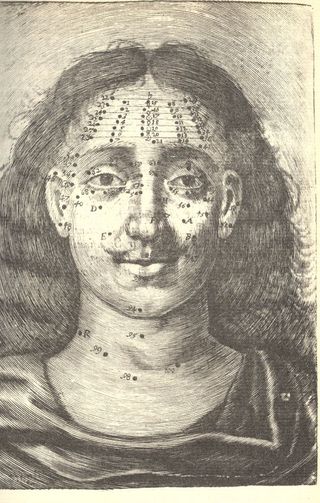

Moving on to Richard Saunders (who I wrote about more fully here)continued a very ancient tradition into England, deep into modernity, by mapping the divine cosmos of moles and other facial extras for the purposes of health and prophecy:

Richard Saunders. Physiognomie and Chiromancie, Metroscopie, the Symmetrical Proportions and Signal Moles of the Body, Fully and Accurately Explained; With Their Natural Predictive Significations Both to Men and Women (published in London, 1671, by Nathaniel Brook).in which he divines the psyche and the future with peoples’ moles.

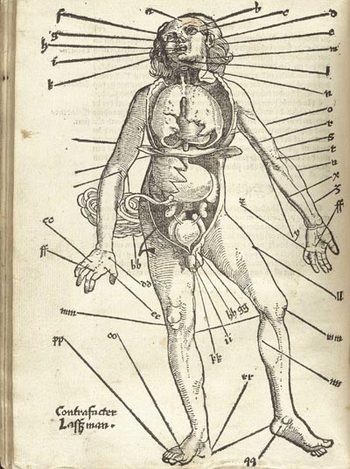

Visceral Anatomy From Reisch's "margarita Philosophica," Johann Schott, 1503

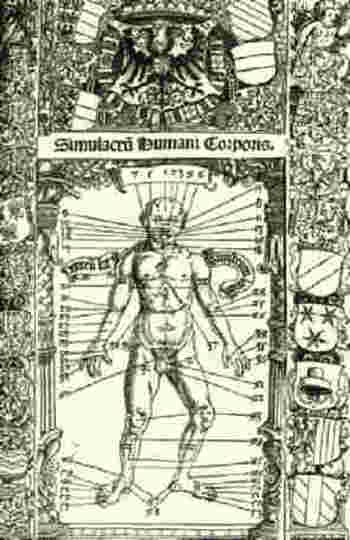

I couldn’t let the above-mentioned bloodletting image pass without reference to this excellent woodcut for Johann Stoeffler’s Calendarium Romanum Magnum, printed in Oppenheym by the redoubtable Jacob Koebel, (24 March) 1518. It is a glorious display (entitled Simulcarum humani corporis) of seasonal (!) purgative and bloodletting locations on the body, meant to accompany a longish essay by Stoeffler on the practice in general. The bulk of the book, however, had very little to do with this practice and was actually commissioned as a reform to the Julian calendar, provided with the impetus of the Lateran Council (1512-1517). The result was a series of forty-one propositions on the calendar and calendar-related practices, including work on eclipses, the zodiac, the occurrence of leap years, the Alexandrine and Roman calendars, the calculation of the occurrence of Easter, and so on, including the seasonal practices of bloodletting.

I couldn’t let the above-mentioned bloodletting image pass without reference to this excellent woodcut for Johann Stoeffler’s Calendarium Romanum Magnum, printed in Oppenheym by the redoubtable Jacob Koebel, (24 March) 1518. It is a glorious display (entitled Simulcarum humani corporis) of seasonal (!) purgative and bloodletting locations on the body, meant to accompany a longish essay by Stoeffler on the practice in general. The bulk of the book, however, had very little to do with this practice and was actually commissioned as a reform to the Julian calendar, provided with the impetus of the Lateran Council (1512-1517). The result was a series of forty-one propositions on the calendar and calendar-related practices, including work on eclipses, the zodiac, the occurrence of leap years, the Alexandrine and Roman calendars, the calculation of the occurrence of Easter, and so on, including the seasonal practices of bloodletting.

I enjoyed this torso map by Salomon Alberti in his Historia plerarumque partium humani corporis, in usum tyronum edita. Vitebergae (p1583, 8°; ibid., 1585, 8°; enlarged, ibid., 1601, 8°;(published from 1583 to 1630) for it simplicity.

The rest of the images I'm going to have to show here as a simple Image Dump, at least for the time being:

Continue reading "Mapping Humans, 1400-1759: Bloodletting, Moles, Bumps and the Stars" »