JF Ptak Science Books Post 1943 (Part of the series on the History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things.)

"Where is abstract without solids, I ask you?" -- William Gaddis, on the solids in Uccello, The Recognitions, 1955

Actually, I think that there's plenty of abstract without solids, so long as you've seen solids before.

I've returned to a slightly recurrent theme in this blog dealing with the great Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) and his study of perspective--but most directly as he was observed by William Gaddis in his Great American Novel The Recognitions. (I am forever grateful to my brilliant Patti Digh for really hooking me into Gaddis so many years ago--Patti was long intrigued by Gaddis and wrote her UVa master dissertation on his Big Book. Gaddis' book can be found here.) Among other things Uccello is recognized as being one of the greatest and among the earliest artist to re-discover the science of perspective, and was throughout his life a passionate student and practioner.

[Much of Uccello's work can be found at Paolo Uccello Complete Works website, here.]

[Much of Uccello's work can be found at Paolo Uccello Complete Works website, here.]

"Painting is exquisite as the punishment for the thinker."--William Gaddis, The Recognitions

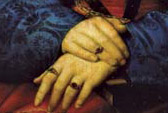

The “solids’ recognized by Gaddis (and not really

discussed, and mentioned only twice in the book I believe) are incredible to me. Looking at his painting Battle of San Romano

(1457) we see Perspective in her place; but when we look at, say, the rumps

of the horses, we see almost no detail, just a mass of color, a solid,

with spectacular plainness. What in the world was he thinking? He could

certainly have painted the horse and the other solids with texture and

detail, but he didn’t, and to me it seems antithetical to the painting.

What in the name of all motherly things was he thinking? And who else

on earth was using such huge amounts of plain solids in their

paintings? I’m not aware that anyone else was, and I am relatively

clueless as to why he did it, abandoning detail in order to raise awareness of the surrounding parts of the painting, or perhaps heightening a sense of the not-yet-existent abstract, or drawing attention to the perspectival aspect of the work?

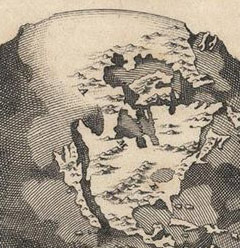

[A detail of the missing detail, above.]

[A detail of the missing detail, above.]

But the solids are not just limited to Uccello, though they may have appeared there first, especially as the "exhibited" variety of this thinking. Jacopo Bellini (ca. 1400-ca. 1470) was a contemporary, living pretty much during the same period of time as Uccello, and who was responsible as much as anyone else for introducing oils in painting and establishing the Venetian style. He was a brilliant artist, the teacher of Mantegna, ran a fabulous studio, and was the father of two great artists. (One son, Giovanni, was a highly regarded artist who was also the teacher of Girgione and Titian.)

In looking through two volumes of Jacopo's drawings, I was struck by the number of times that horses and other objects appeared without detail, as solid solids, or mostly solid, quite outside the way in which these things were painted in the 15th century. Pacing though the books flipping through the open pages is like looking at a pop-up book in reverse--each set of pages opened are like looking into, looking through, the book, into space. They are collections of perspective. And they are populated by those other solids, which was surprising.

His horses appear very much like those in Uccello--except of course that these images were personal, workbooks for the artist, idea-machines and memory devices. There was plenty of detail in other aspects of these drawings, but the lack of the detail int he Uccellian manner really struck me.

Christiane L. Joost-Gaugier's "Jacopo Bellini's Interest in Perspective and its Iconographical Significance" found in Zeitschrift fuer Kunstgeschichte (1975)

makes a very learned and eloquent case for the overwhelming interest

that Belinni had in the study of perspective--not to the exclusion of

all other things, because there were still patrons to be satisfied and

religious and triumphal scenes that needed to be painted--and

concentrated on that interpretation focusing on Bellini's stylebooks.

(Most of Bellini's output has been lost, but there are two volumes of

manuscript studies that have survived.)

"Though

many of Jacopo Bellini's drawings are reminiscent of model-book notions

in that they illustrate a variety of suggestions for the representation

of traditional themes - for example Flagellations, Adorations, Davids,

and animals -they are, taken as a whole, entirely different from model

book drawings. Jacopo rarely concentrated on a subject for the sake of

its thematic content. Almost never does a bald statement of fact appear

to describe, for example, a biblical event. Rather than focusing on the

event itself, Jacopo's compositions characteristically are concerned

with other things. In the vast majority of cases the subject is set

within the context of a variety of architectural motifs or in that of an

extensive naturalistic world. It would appear that for Jacopo Bellini

biblical subject matter was a justification for his participation in a

variety of other new interests. Primary among these was the special

attention given to perspective..."

No mention of course of the Uccello horses. And perhaps they're really not there there, but it certainly looks like they are, at least to me. They might not have been there for Gaddis, either, as Bellini doesn't show up in the book, Gaddis thinking more about Uccello, and then even more so of

Hieronymous Bosch,

Hugo van der Goes, and

Hans Memling.And here it is, Bellini's solids, an example:

There are others as well, examples of what, I am not sure--fantastic visions into blankness and into the future of what painting would become 450 years hence.

Perhaps they were just place-keepers, to be filled-in as neededm just a shrt-hand expression of a horse rather than a transcendental imperative. After all, Bellini knew horse muscles, and decided in his workbooks that he just didn't need to draw them, or that in the sense of Bartleby the scrivener that he'd prefer not to.

Notes:

![]()