JF Ptak Science Books Post 1934

An entry in the series on the History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things.

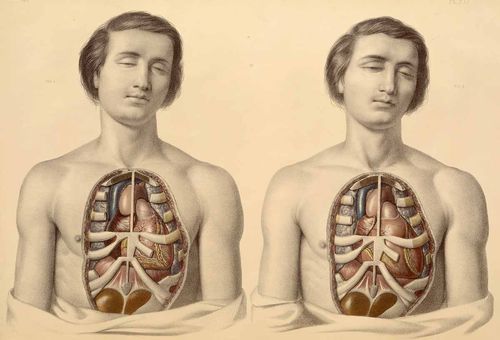

This is fascinating--the anatomist Francis Sibson (1814-1876) in his Medical Anatomy (London, 1869) provided descriptive/illustrative examples of what the body's internal organs look like in cadavers and in living patients. Offhand I am not aware of such a comparison being done before this date, and as he clearly demonstrates (and which you can see more clearly by expanding the above example) there is of course a huge difference in the anatomy of the living and the deceased.

This is an enormous observation that seems as though it should have been made earlier, but perhaps it wasn't--though it must be admitted that "the obvious" isn't until it is. For example, Etienne Durand was the first architect to include examples of plans of different buildings on the same scale side-by-side, and that wasn't until the mid-19th century--clearly this would be pro forma for just about describing two elements of anything, but it just simply wasn't done until 160 years ago or so. This also applies in a way (though there are more complexities involved as to why this is different) to the antisepsis practices of Joseph Lister who in simply washing surgical tools between use on different patients (and hand-washing and the use of surgical masks and so on) increased the chances of surviving surgery by at least 50% (though I think that number is much bigger than that), and these practices weren't begun until the mid-19th century.

So the business of identifying "the obvious" is very tricky, because, well, something isn't obvious if it hasn't been done/seen before. Or, if it has been seen, it hasn't been seen seen. As in clouds--as present as they have been for the whole of human history they basically escaped classification by the great human natural history classifiers until the very early 19th century.

And when I looked at the history of the word "obvious" it seems to have made its first appearance in print in 1603, so I went naturally to William Shakespeare for a quote using the new word. Evidently, the great wordweaver never used "obvious". (See here for an index of all the words of Shakespeare.)

[Image printed by chromolithography after the artwork of William Fairland, 1869. Source: the National Library of Medicine.]

I've been keenly interested in this subject for years. In my own research, I've found that gaining awareness of distinctions was probably not a matter of pointing out the obvious, but rather a two-step process:

1.) Becoming aware for the first time of the existence of a distinction.

2.) Communicating that distinction to others in a conscious fashion, through the written & spoken word, as well as through action.

It is not sufficient to communicate a difference through words &/or pictures without being at least minimally conscious of it.

Heraldry demonstrates this. European heraldry was one of the earliest vocations to attempt a technically precise & standardized verbal description of visual objects. Early verbal heraldic descriptions of armorial bearings are surprisingly accurate about the color, aspect, & position of shapes & symbols on a shield, yet glaringly imprecise about other visually important features.

An example is heraldry's treatment of number: among the charges (heraldic symbols) used on coats of arms, the star or "mullet" may have any number of points from four to eight; but the manner in which the points of the star are drawn (stright or wavy) & the the way its center is treated (pierced or unpierced) have been far more important to its heraldic evolution than the number of its points.

Detailed specification of the number of points on a mullet or star has only entered heraldic descriptions relatively recently--at some time within the last couple of centuries.

What is true of the star or mullet is also true of other heraldic charges: number as it affected the forms of certain charges was often imprecisely specified, although the QUANTITIES of identical charges were exactly noted as a rule.

Within European culture, consciously marked visual distinctions generally seem to have been relatively recent phenomena. It has taken centuries--in heraldry, & perhaps in other fields--for obvious distinctions to become obvious.

Posted by: RetroCollageArt | 16 November 2012 at 12:13 PM