JF Ptak Science Books Post 2769

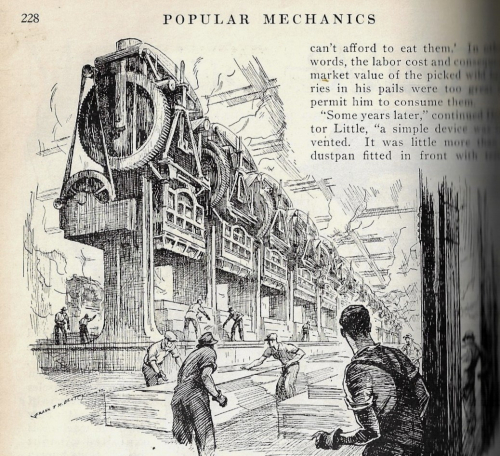

This unexpected and somewhat philosophical article on the social standing of The Machine appeared in Popular Mechanics in 1932. A standard-bearer for oil and sawdust, sparks and steam, Popular Mechanics was much more interested in DIY than sitting deep in the leather chair to have a long think on the cultural implications of the stuff of the Machine Age. It spoke more about how to manufacture a bolt more so than why one should do so.

This unexpected and somewhat philosophical article on the social standing of The Machine appeared in Popular Mechanics in 1932. A standard-bearer for oil and sawdust, sparks and steam, Popular Mechanics was much more interested in DIY than sitting deep in the leather chair to have a long think on the cultural implications of the stuff of the Machine Age. It spoke more about how to manufacture a bolt more so than why one should do so.

"Machines--Masters or Slaves?" is the name of the article and it really does ask the question, and in the present tense. It is easier to imagine having this discussion about the machines of our future--or rather in the machines' future, because it is conceivable that beyond the Singularity that over the course of the next century of five that "machines" may not have much of a need for humans. In any event, five leading techie lights give their assessment of who-rules-whom back there in 1932.

One of the unexpected assertions (and unfortunately unexplained) belongs to Raymond Fosdick from the Rockefeller Foundation Machines, who said that machines have "fastened" themselves on every detail of our lives" and then "they have called into being millions of people who might otherwise had not been born". He says that machines have reached into every part of the world, "for hundreds of millions they are the sole means of support. Stop the machines and half the people in the world would perish in a month", where he is probably talking about mechanized food production and delivery.

Another surprising summation came from Dr. W.E. Wickenden (Case School Applied Science) along these lines: if somehow all and every machine were discontinued and removed and all of their duties were transferred "back into human muscle" to do the job that "we should need at least five billion human slaves" to carry on the work.

At this point co-development of machine and human was not an issue, though it would be and famously so in about 18 years. Machines still stood on their own, and the product of human-machine communication and advanced interaction was still the stuff of the newly-burgeoning field of science fiction. The great question posed by Alan Turing, "May not machines carry out something which ought to be described as thinking but which is very different from what a man does?” (in “Computing, machinery and intelligence.” Mind LIX (236), 433–460) will have a lot more to do with the future of "machines" for us now and in the future than was ever expected of the "us" of 1932.

Another contributor, William Green, president of the A.F.L., took stock about some of the costs of machines: as wonderful as they were, they cost people their jobs, and lists some of the human costs of mechanization. "In the manufacture of razor blades, one man can now turn out 32,000 blades in the same time needed for 500 in 1913. In the machine shops one man with a gang of semi-automatic machines replaces twenty-six skilled mechanics". He didn't mention the Luddites, a secret group bent on preserving jobs decimated by automation by going out and destroying the machines replacing humans. The term is used differently today-often meaning someone who prefers and older tech or non-tech alternative to a tech instrument; that, or simply not knowing some technical subject. The original use was in relation to labor practices, standing against machines that would rob people of their livelihoods. For example, the handweaver population n England stood at 240,000 in 1830 to 43,000 in 1850 after the introduction of the mechanization of stocking and spinning frames, which made for 207,000 not-satisfied people. Anyway the Luddites set out to curtail the replacement of workers by machines and the making of unfair profit by the owners of the means of production, though they didn't get very far.

Of course the replacement of workers by machines would continue on the scale of an order or two of magnitude, until finally the machines themselves were replaced by other machines operated more cheaply in other countries.

Ultimately the author comes down on the side of the machine as slave rather than the human, because "as an instrument of exploitation or profiteering the machine is doomed by common sense", "the veiled splendor of the moral vision" in the 'unending future of the machine", whatever that means. The machine was a servant of humankind, lifting us from "drudgery", into a "greater leisure for the exercise of the free spirit". No doubt this is all giveth/taketh--I wonder how far into the future it all becomes taketh/giveth?

Comments