JF Ptak Science Books Post 2491 Part of the series History of Atomic and Nuclear Weapons

Earlier in this blog in 2010 there appeared a post called "Atomurbia: Responding to Atomic Threat by Moving Everyone Everywhere, 1946"--it turned out to be very popular, being about the dispersal of the U.S. population centers to thwart nuclear attacks. (I'll repeat: it was about the plan to redistribute the population and industry and appropriate infrastructure of the United States of America.)

It was of course (as Somerset Maugham would say in "The Three Fat Women of Antibes") an Enormous Situation, involving (basically) moving everyone everywhere. The term was "dispersion", and the planners of such plans meant it--and I've come across it again--unexpectedly--in another issue of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists for September 1951.

You may recall that this is the journal that keeps a doomsday clock ticking off the minutes on its front cover showing the advance or retreat from the Midnight of Armageddon. On this issue the clock is at three minutes to midnight, though I think that the greatest distance from the zero hour was ten minutes to the hour--so for decades the clock has been very close to striking the doomed hour without much relief.

In this issue of the Bulletin nearly every article is dedicated to the idea of dispersion (at that point under the auspices of the National Security Resources Board) and the creation of a federal program to directly oversee dispersion (the National Defense Dispersal Administration (NDDA)). And people are talking about moving around cities and people and industry as though it wasn't that big a deal, though I must admit I haven't seen any cost or time estimates in this source. Moving the populations centers of the U.S. to a more "garden city" idea involves so much effort and expense it seems almost impossible to contemplate actually paying for all of it. (And we haven't begun to talk about how people and essential personal are actually 'enticed" to leave their surroundings, nor is there any talk about the property rights of the owners of all of that land that is to be built on.)

As much as Frank L. Wright's "Broadacre City" seems to be a lead balloon so far as actual implementation goes for size and scope, this type of "dispersion" idea would be of gargantuan, orders-of-magnitude bigger/costlier than what Wright was talking about. At least in this department Wright was thinking in terms of a utopia; the dispersion business was more like a dis-utopian-dystopia, or something, no matter how these authors attempted to green-up and de-slum their proposal.

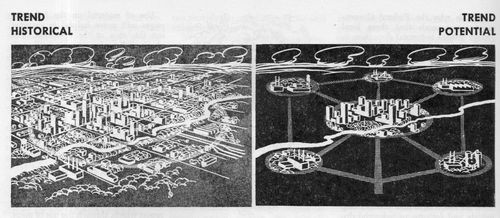

I am mostly making this post for the image at the top of this post(from page 268 of the Bulletin), which fits nicely with those others posted in the earlier Bulletin article (reproduced in the link above).

Comments