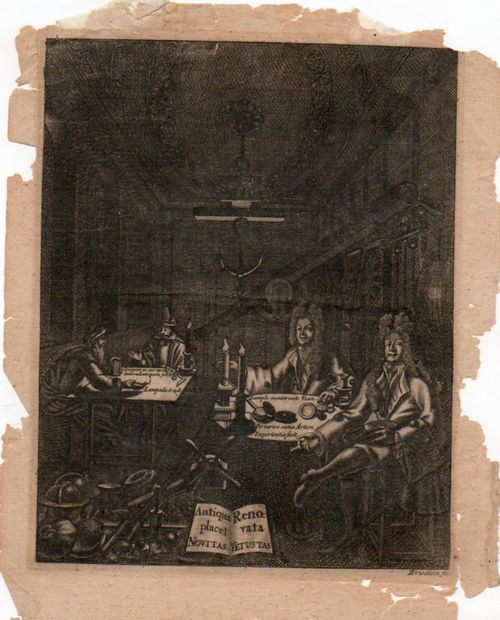

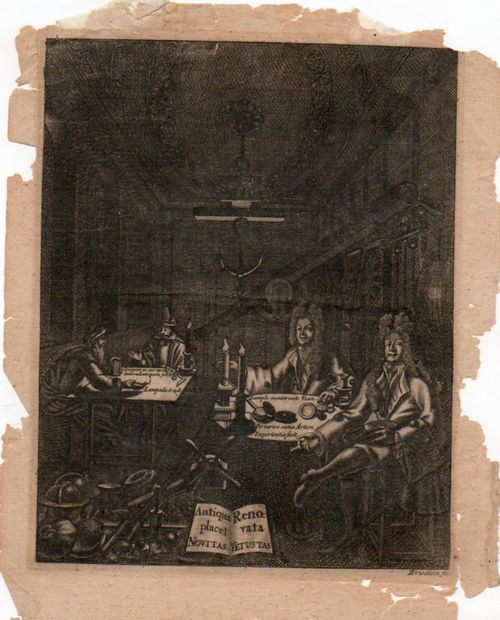

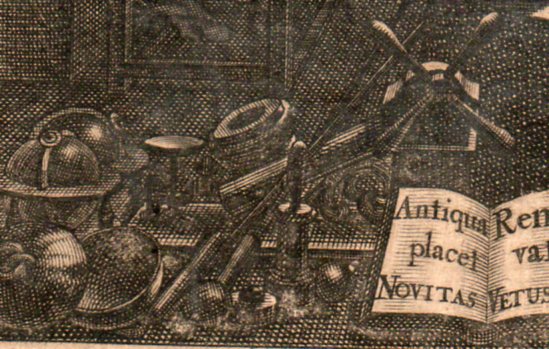

This is an image of a philosopher's cabinet, engraving (on copper?) by "I. Friedlein fec", who was Johnann Friedlein, an emigree from North Germany to Denmark, and who worked ca. 1680-1705. It shows the tools of the trade for someone working in natural philosophy (the name "scientist" would not come into use for another 130+ years or so1) and is an interesting insight into a small, polite gentleman's club for experiment and investigation.

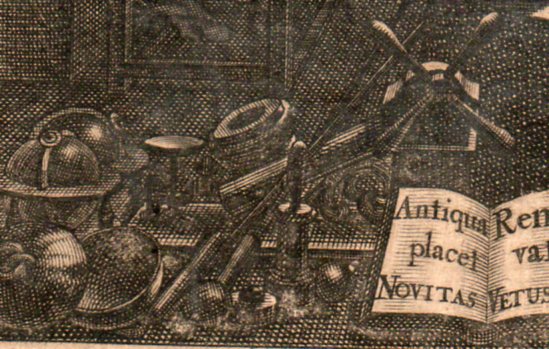

The men surround a decent collection of scientific instruments--I can locate a compass, dividers, oil lamp, magnifying glass, microscope2 (at the right elbow of the figure on the right), terrestrial and celestial globes, a (large) clock, barometer, and various weights and scales, and behind it all looms a rather large refracting telescope3 (is it five inches?)

For all of these expensive and current instruments, the lighting these gentlemen set up for themselves is pretty poor, though of course it does add to the mystery and dark experience of the image.

Here's another example of Friedlein's work, a frontispiece to Cryptographia, oder geheime Schrifften by Johann Balthasar Friderici, printed in 1685:

Nyt dansk kunstnerlexikon: bd. Indenlandske kunstnere (fortsættelse ...)by Philip Weilbach:

Notes:

1. "Scientist", in the Oxford English Dictionary ("science" is a much older word in English):

1. A person who conducts scientific research or investigation; an expert in or student of science, esp. one or more of the natural or physical sciences.computer, earth, mad, natural, rocket scientist, etc.: see the first element.

It is possible that the ‘ingenious gentleman’ referred to in quot. 1834 is Whewell himself.

1834 W. Whewell in

Q. Rev. 51 59 Science..loses all traces of unity. A curious illustration of this result may be observed in the want of any name by which we can designate the students of the knowledge of the material world collectively. We are informed that this difficulty was felt very oppressively by the members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, at their meetings..in the last three summers...

Philosophers was felt to be too wide and too lofty a term,..;

savans was rather assuming,..; some ingenious gentleman proposed that, by analogy with

artist, they might form

scientist, and added that there could be no scruple in making free with this termination when we have such words as

sciolist, economist, and

atheist—but this was not generally palatable.

1840 W. Whewell

Philos. Inductive Sci. I. Introd. p. cxiii, We need very much a name to describe a cultivator of science in general. I should incline to call him a

Scientist. Thus we might say, that as an Artist is a Musician, Painter, or Poet, a Scientist is a Mathematician, Physicist, or Naturalist.

2. "Microscope" (as a noun) in its earliest uses in English, in the OED:

1648 Bp. J. Wilkins

Math. Magick i. xvi. 115 We see what strange discoveries of extream minute bodies, (as lice, wheal-worms, mites, and the like) are made by the Microscope, wherein their severall parts (which are altogether invisible to the bare eye) will distinctly appear.

1651 N. Highmore

Hist. Generation viii. 70 The white circle..by a Microscope appears now to be the Carina or back and neck of the Chick.

3. "Telescope" (as a noun) in its earliest uses in English, in the OED:

[1619 J. Bainbridge

Astron. Descr. Late Comet 19 For the more perspicuous distinction whereof I vsed the

Telescopium or Trunke-spectacle.]

1648 R. Boyle

Seraphic Love (1663) xi. 59 Galileo's optick Glasses,..one of which Telescopioes, that I remember I saw at Florence.

Comments