JF Ptak Science Books Post 2358

Well, what was really being picked up was the canvas on which an enormous panorama of the Mississippi River was painted. The work was that of New Yorker John Banverd (1815-1891), a portrait painter who awoke with the notion of displaying the shoreline of the Mississippi River for its entire length. To that end he raised money (based on his painting income and investments) and set out with his $3000 in a skiff to paint the river, back in 1840. According to a pamphlet that describes his effort (the full text of which is available at the Internet Archive, here), the effort took over 400 days--when his sketches were complete Banverd repaired to St. Louis where he built a wooden house specifically designed for him to transfer his sketches to an immense canvas. The work was completed in 1846, at which point his work was 12' high and 1500' long--by 1848 the length of the work expanded to 2600'. (Banverd advertised his work as being "3 miles" long--that wasn't the case, and that's okay, because he had produced one of the largest paintings ever produced by a human.

The panorama (and diorama, and cyclorama, and other iterations of 'raams) were a very popular entertainment form, as popular as plays and other similar exhibits and spectacles, lasting deeply into the 19th century. The Branverd panorama was on a large canvas that was advanced like a mechanism on a 35mm camera film advance--there were other sorts of displays, one of which kept the canvas static with the audience walking past it; others took place in a rotunda where the pano was on the walls of the structure and observers would be on a platform in the middle, where they would achieve a motion picture-like effect by turning slowly to see the entire image.

There were many panorama subjects, including subjects like Jerusalem, London, Rome, Lima, a journey down the Rhine, and so on. The medium would take a fatal hit with the invention of flexible roll film and the accessibility of photography to the masses, the invention of the half-tone making it possible to reprint photographic images in newspapers and magazines, and other bits that could generate images from everywhere and cheaply.

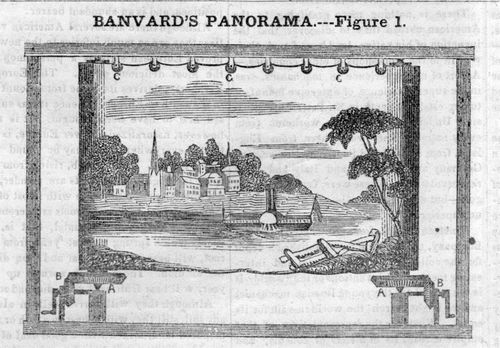

The panorama was taken by Banverd on a tour of major cities where people would pay a fee to see the gigantic artwork displayed before them, shown segment by segment on a large frame with cranks that would roll/unroll/collect the painting before the audience, almost like a very primitive movie.

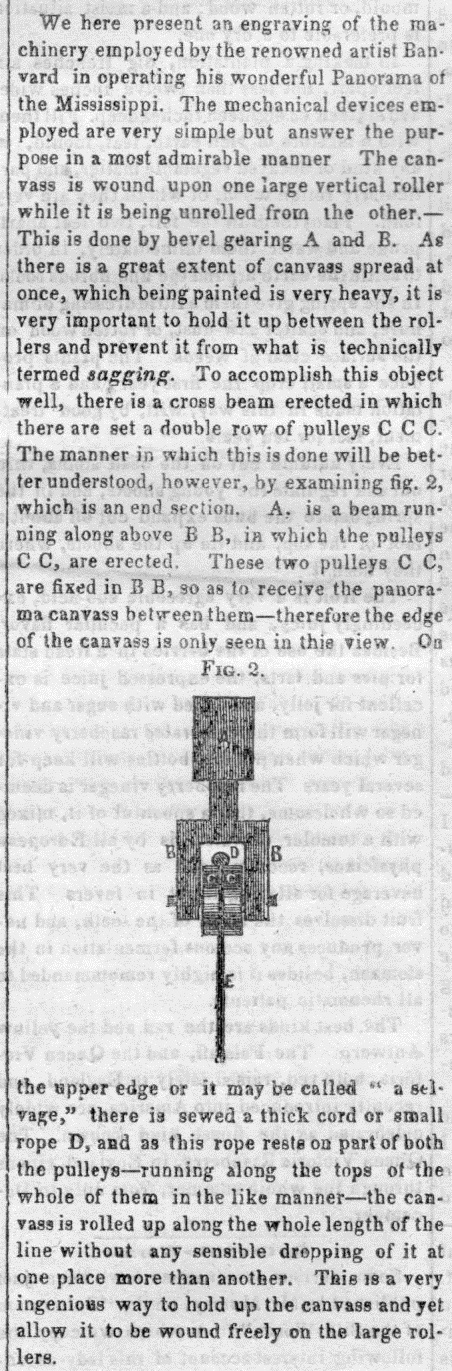

The image above is from The Scientific American for December 10, 1848, and shows how Mr. Branverd figured out a knotty problem with the display of his super-massive work. Unfortunately, at the end of the life of the canvas it was cut into smalkl fragments and sold--evidently none of it survives.

Comments