JF Ptak Science Books Post 2321 A Post called "Computer Art, 1949", revisited and much expanded

This is a great example of an exactly-what-is-this object, something that seems to be one thing, then the other, but then neither.

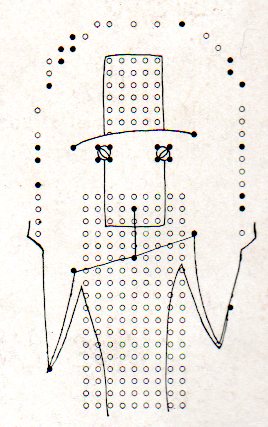

I'm not sure how to investigate this right off-hand, but I think that there is a special category in the history of art, subcat history of art and technology, subcat history of computer art, subcat using the technical aspects of the computer in art. The image above comes from the front cover of one of the early issues of the "new" Physics Today magazine (volume 2, number 10), in October 1949--it is the artwork of Paul Bond, who created this portrait of a juggler "on a matrix sheet used for plotting computor [sic] plug board diagrams", and is one of 11 such images. So, while not computer art--artwork generated by the computer--it is artwork using items designed to operate the computer, a sort of very early computer-material montage. (It would be in the first-time-ish category, but I can't say this with any surety--it is however very very early for what it is.)

I'm not sure how to investigate this right off-hand, but I think that there is a special category in the history of art, subcat history of art and technology, subcat history of computer art, subcat using the technical aspects of the computer in art. The image above comes from the front cover of one of the early issues of the "new" Physics Today magazine (volume 2, number 10), in October 1949--it is the artwork of Paul Bond, who created this portrait of a juggler "on a matrix sheet used for plotting computor [sic] plug board diagrams", and is one of 11 such images. So, while not computer art--artwork generated by the computer--it is artwork using items designed to operate the computer, a sort of very early computer-material montage. (It would be in the first-time-ish category, but I can't say this with any surety--it is however very very early for what it is.)

It reminds me in a way of a magazine article using the illustration of a photograph--it was in the curious category of the first time an image of a photograph was published, that is to say it was a woodcut of a photograph though not the photograph itself. This appeared in Golding Bird's series of articles, "A Treatise on Photogenic Drawing", which was five papers found and bound in the London-published journal, The Mirror. and were extremely works on the new science of photography, appearing in issues from April 20-May 25, 1839. The image appears on page 241 (issue no. 945, Saturday April 20) and displays this first image of a photogenic drawing, which was the first publication of an image produced by any sort of photographic process. (The process here is the 'sun picture" , a photographic process, making this the first published "photographic" image, but really it is more like the first publication of a photographic image that was produced via woodcut. It predates the first mass-published photograph by four years and the first (entirely) photographically illustrated book (The Pencil of Nature ) by six years.)

Our computer artwork illustrates an interesting article ("Modern Computing") by pioneers R.D. Richtmyer and N.C. Metropolis . Richtmyer/Metropolis have a very sober approach to the computer--and mostly speaking about the ENIAC--and address its romance, possibilities, and seemingly (to me) most of all "a need for defining the limits of computing machine operation, as well as its promise". In effect, the authors really only address the known quantities of computing capacity in 1949, and even though tempted by looking into the future, they really do not. Their vision of the future is very pragmatic, and so far as speaking to future applications of the machine they choose the very Bartlebian philosophy and chose not to: they conclude "by their very nature, these applications are not easy to foresee, and perhaps, therefore, this is the point at which this discussion should close", preferring to watch the beautiful and complex whirlwind in a thicket from the outside.

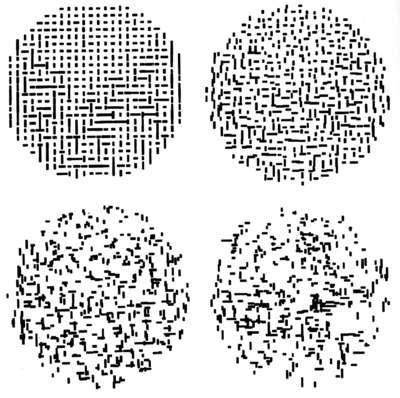

There have been much earlier images of automated steam-driven robots with some sort of calculating brain, and images of imaginative computer-like objects, and stretching back into the 18th century, so the idea of creativity and thinking and human-like qualities made by things constructed of metal and wood with a power source of steam or electricity and so on was well-established, though lurking in deep-background. Art made with the computer seems to come a fair bit later than this issue, later still than what might be considered the first art generated via the computer (which were images made from manipulating an oscilloscope) in 1952. This was the work of Ben F. Laposky (1914-2000) an Iowan and mathematician/draftsman and former sign-painter who took long time exposure photographs of waves motions on a cathode ray oscilloscope with sine wave generators and found beauty in them. His work was first exhibited at the Sanford Museum in Cherokee, Iowa, in 1952, as "Oscillons or Electronic Abstractions"1 --hundreds of other shows would follow.2 One of the earliest appearances in print of the oscillons is in Scripta Mathematica, Sept-Dec, 1952, pp 305 (and then somewhat later in Design, May 1953).

Among the earliest computer-generated art--that is, art made via an automatic process input by humans by created by the machine--was created and noted by A. Michael Noll (b. 1939) with an IBM 7094 and described as "computer art" in "an August 1962 technical memorandum"3. Noll has written extensively (and interestingly! and early) on human/computer interfaces including computers and dance, fourth dimensional imaging, and much else4, including a fabulous comparative study of an original Mondrian and a computer-generated alternative5. (Noll is today widely recognized as one of the first in the field of digital art and 3-D animation.)

[Image source: Compart, Cener for Excellence in Digital Art, here.]

In any event, I think at the very least that the Bond artwork is very curious, interesting, and probably very early for what it is.

1. This reference was first found in Arthur I. Miller's Colliding Worlds, (Norton, 2014) on page 66. Miller is perhaps the most upper tier in upper tier historians of science with the specialty of art/science interface--over the years I have enjoyed his work enormously.

--See here for a full text of Electronic Abstractions.

2. "Electronic Abstractions are a new kind of abstract art. They are beautiful design compositions formed by the combination of electrical wave forms as displayed on a cathode-ray oscilloscope. The exhibit consists of 50 photographs of these patterns . A wide variety of shapes and textures is included. The patterns all have an abstract quality, yet retain a geometrical precision . They are related to various mathematical curves, the intricate tracings of the geometric lathes and pendulum patterns, but show possibilities far beyond these sources of design."—Sanford Museum, Gallery notes for Electronic Abstractions, 1952 (Wiki) For a good appreciation of Laposky, see Alison Drain, "Laposky's Lights Make Visual Music" in Symmetry 4/3, pp 32-33.

3. Miller, page 68.

4. See the following:

Noll, A. Michael, “Short-Time Spectrum and Cepstrum Techniques for Vocal-Pitch Detection,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 36, No. 2, (February 1964), pp. 296–302

Noll, A. Michael, “Computers and the Visual Arts,” Design and Planning 2: Computers in Design and Communication (Edited by Martin Krampen and Peter Seitz), Hastings House, Publishers, Inc.: New York (1967), pp. 65–79.

Noll, A. Michael, “The Digital Computer as a Creative Medium,” IEEE Spectrum, Vol. 4, No. 10, (October 1967), pp. 89–95

Noll, A. Michael, “Choreography and Computers,” Dance Magazine, Vol. XXXXI, No. 1, (January 1967), pp. 43–45

Noll, A. Michael, “The Effects of Artistic Training on Aesthetic Preferences for Pseudo-Random Computer-Generated Patterns,” The Psychological Record, Vol. 22, No. 4, (Fall 1972), pp 449–462.

Noll, A. Michael, "Computer-Generated Three-Dimensional Movies," Computers and Automation, Vol. 14, No. 11, (November 1965), pp. 20-23.

Noll, A. Michael, “Computer Animation and the Fourth Dimension,” AFIPS Conference Proceedings, Vol. 33, 1968 Fall Joint Computer Conference, Thompson Book Company: Washington, D.C. (1968), pp. 1279-1283

Noll, A. Michael, “Art Ex Machina,” IEEE Student Journal, Vol. 8, No. 4, (September 1970), pp. 10-14.

5. Noll, A. Michael, “Human or Machine: A Subjective Comparison of Piet Mondrian’s ‘Composition with Lines’ and a Computer-Generated Picture,” The Psychological Record, Vol. 16. No. 1, (January 1966), pp. 1–10.

Comments