JF Ptak Science Books Post 2270

[Image sources: National Library of Medicine.]

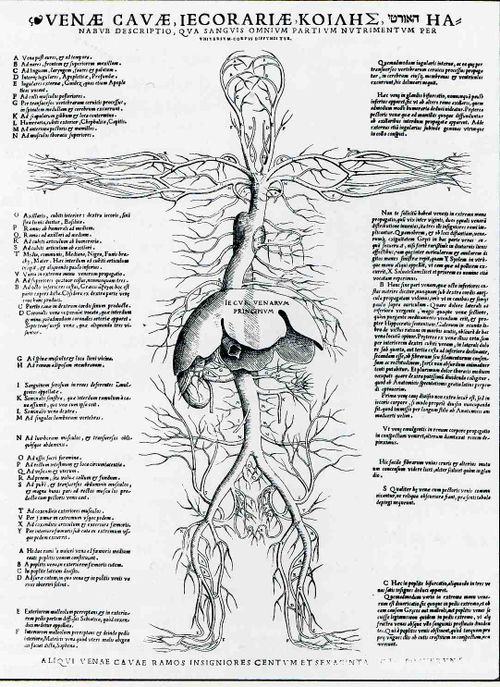

In 1664 Philipp Jakob Sachs (Sache de Lewenbheimb) wrote an influential book on the circulation of the blood. It was the advanced work of a learned man, a naturalist and physician who was also the editor of the Ephemerides Academiae naturae curiosorum, which was the first journal in the field of natural history and medicine and one of the founders of the Academia Naturae Curiosorum (Leopoldina). His work came 40 years after the great work by William Harvey, who published Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus in 1628, a work in which he essentially brought the idea of circulation of the blood into the modern age, building on earlier ideas of Michael Servetus, whose 1561 work on circulation (and his religious ideas) brought him to be executed by flames.

For centuries the pulse was a vaguely understood thing reaching back into the murky medical past as far back as Galen. The association of course was with the heart, and the association of the heart was as the great controlling center of all function and control of the human body—a theory that reached far forward into the 16th century.

Servetus (physician, cartographer, theologian, writer and general all-adept Humanist of a high order) was in trouble with the church for many reasons, not the least of which was trying to dislodge the theory of the heart as sacred and the seat of wisdom. But he did establish that the heart was an organ, which didn’t sit well with very many people, least of all the Calvinist court in Vienna which found him guilty on many anti-Humanist grounds, including his anti-Trinitarian Christology, which made him a reviled figure to Catholics and Protestants. He was tried and found to be dangerously heretical, and sent to the flames.

Harvey withstood blistering attacks on his correct statements on the circulation of the blood (costing him nearly all the patients in his practice), though he at least lived to see a brighter day: Servetus, on the other hand, didn’t, and was burned at the stake for his heresies, one of which his attack on the spiritual heart.

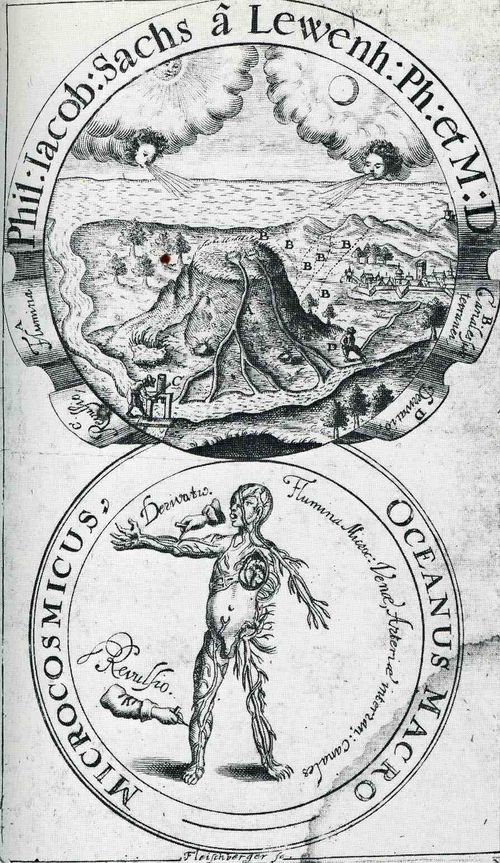

In any event, the frontispiece to Sachs' work is an interesting allegorical composition showing a connection between the place of the very prominently featured heart in the circulation of the blood, and the water cycle, and the cosmos of creation (the breath of life coming from the winds of the Sun and the Moon).

Notes: (Sachse de Lewenheimb, Philipp Jakob Sachs, 1627-1672 , Oceanus macro-microcosmicus, seu Dissertatio epistolica analogo motu aquarum ex et ad Oceanum, sanguinis ex et ad cor... 1664, with full text via Google books here).

Comments