JF Ptak Science Books Post 2199

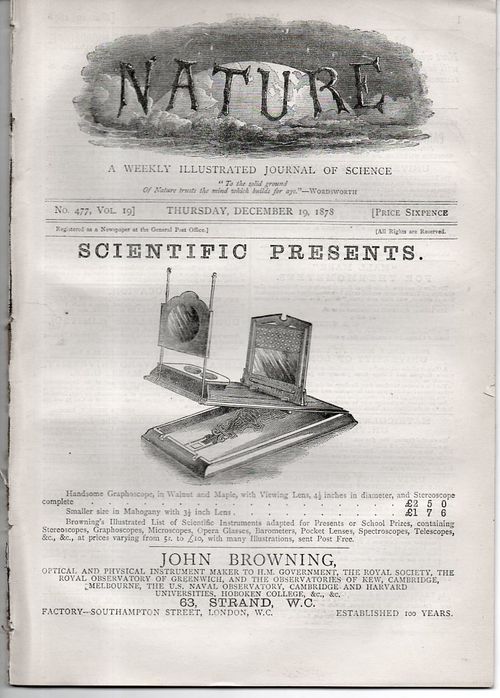

One of the great pleasures in the business of antiquarian science book selling is the Advanced Ability/Capacity to Browse the books. Or Graze. All in the semi-pursuit of an undefined goal that sometimes leads to something that leads to something else, and sometimes all of them get pulled together. And so this came to be last night, working my way through an issue of Nature, a Weekly Illustrated Journal of Science, for December 1878--and yes, this is the same Nature that we know today, begun in 1869. The modern Nature is massive and perhaps one of the world's foremost publications in the sciences--in 1878, the magazine was a semi-popular, quick-to-publication-and-print journal, usually less than two dozen pages long.

The magazine was short and to the point, and it packed an enormous amount of material on a limited amount of paper--two columns of print per page, 7-10 words per line, 70 lines per column, or about 1500 words per page. (An average novel has about 400 words per page.) It attracted the attention of everyone, and virtually every big name in the sciences in the 19th century seemed to find their way into this publication: Darwin, Huxley, von Helmholtz, Thomson, Maxwell, Hertz, and on and on.

I admit that I was attracted to this issue by the beautiful engraved ad ("Scientific Presents" (!)) for a graphoscope, sold by John Browning (63 Strand) of London. (The graphoscope was an entertainment device created around 1860 and was an elegant/extravagant magnifying glass for viewing photographs and prints and such. The base was lifted to meet the gaze of a seated viewer who would look through the large magnifying glass at an image that was placed on the theatrical/framework bit at the back of the device.)

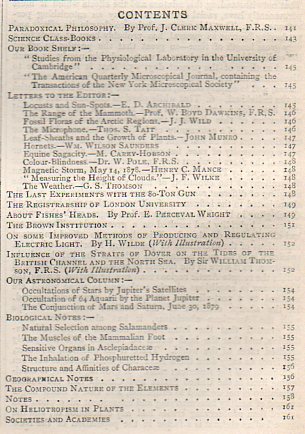

The contents are terrific. The issue starts with a provocatively-titled work by James Clerk Maxwell, a review called "Paradoxical Philosophy", which I like quite a bit--and it is rather long for Nature, and it was a joy to make my way through Clerk Maxwell as he makes his way through the story.

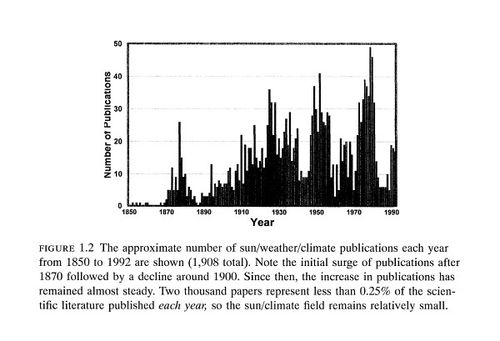

And then: a short piece by E.D. Archibald on "Locusts and Sunspots", which fits nicely into the history of th esun and sunspots and cycles and weather, nicely into teh early-ish modern period. That also brought me to a fascinating book with this great graphic on the history of publications dealing with what I just mentioned.

[Source: The Role of the Sun in Climate Change, by Douglas V. Hoyt, Kenneth H. Schatten Program Director of the Solar Terrestrial Research National Science Foundation.]

[Source: The Role of the Sun in Climate Change, by Douglas V. Hoyt, Kenneth H. Schatten Program Director of the Solar Terrestrial Research National Science Foundation.]

The there is so much more, as we can see:

Tait on the Microphone, Dawkins on the range of the mammoth, Wild on the fossil floras of the Arctic, Carey-Hobson on equine sagacity, Pole on colour blindness, and a beautiful effort by Wilke on measuring the heights of clouds--all lovely efforts.

And then, at the very end, under the unlikely title of "Societies and Academies", emerged a magnificent effort by William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, another very major scientific name, and his effort at constructing a mechanical analog device, a very smart machine that wasn't built until 1932. His "On a Machine for the Solution of Simultaneous Linear Equations" is a remarkable effort, calculating its way through masses of numbers with pulleys and cords, as noted by Tom Woodfin of the MIT AI lab ( here):

"Lord Kelvin proposed one mechanical system in 1878. Designed to solve sets of linear equations, it operated on a tilling-plate mechanism—essentially a collection of pulleys spaced along balanced plates and connected with rope. Coefficients of the linear equations would correspond to pulley placements, and the ropes would be tugged to balance the beams and hence the equations. Results would be read off as the lengths of loose ends of rope."

"Kelvin’s scheme had several advantages. First, it was based on rudimentary technology—within

the capabilities of 19th century craftsmanship. Second, it was possible to increase the precision of a calculation through successive applications of the device, taking advantage of the characteristics of the linear equations it was designed to solve. Third, its mechanical nature made it ideal for “tweaking”—slight adjustments in inputs could be made quickly, and results obtained rapidly, without substantially reconfiguring the device."

All-in-all, the chance meeting with the graphoscope produced a number of very interesting finds, none of which really pulled themselves together in this context, but certainly could possibly play their role as missing pieces in some future puzzle--which is really what all of this is all about.

Comments