JF Ptak Science Books Post 2151

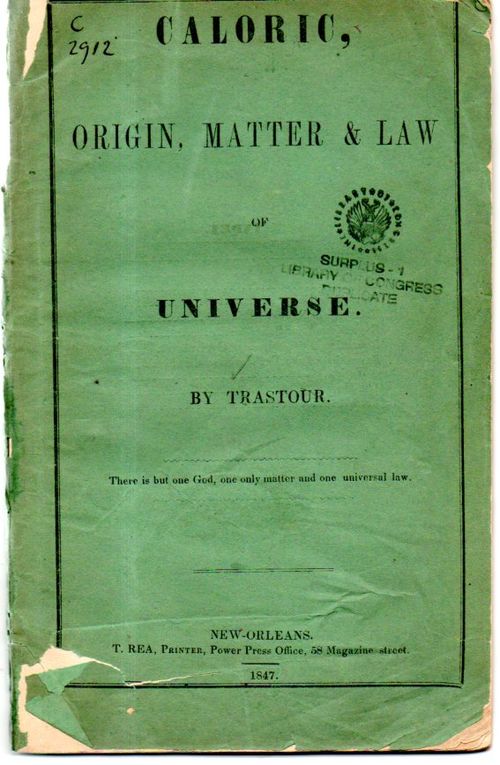

Pierre E. Trastour published this remarkable pamphlet in 1847, in New Orleans, a fragment of what was supposed to be an astounding and magnificent work of science that dispensed with commonly-held understanding of math and physics and astronomy. It was a manuscript Trastour was working on in his engineering travels in South and Central America, something of his great pride. The section that was published, which was translated from the French, did not meet his approval--or so it was said, as some time later he decided that the work was badly translated and interpreted, and sought out to destroy whatever copies he could find as well as all of the copies that remained of this edition. He found them unacceptable.

Pierre E. Trastour published this remarkable pamphlet in 1847, in New Orleans, a fragment of what was supposed to be an astounding and magnificent work of science that dispensed with commonly-held understanding of math and physics and astronomy. It was a manuscript Trastour was working on in his engineering travels in South and Central America, something of his great pride. The section that was published, which was translated from the French, did not meet his approval--or so it was said, as some time later he decided that the work was badly translated and interpreted, and sought out to destroy whatever copies he could find as well as all of the copies that remained of this edition. He found them unacceptable.

His ideas regarding the physical world are, well, quite independent. He addresses "caloric" as the cohesive element of the universe, right on the title page, and then works down from there. My issue is not with caloric per se--I don't intend to have fun with this idea simply because it is obsolete, a remnant of scientific research. Trastour wraps caloric around a lot of adventurous thinking about the nature of gravity and the ridiculousness of Newton. And Kepler. And much else. Caloric is a simple bystander to the rest of this Idea-omat and is used like a club to make the rest of his theory (or from what I can tell of it) work.

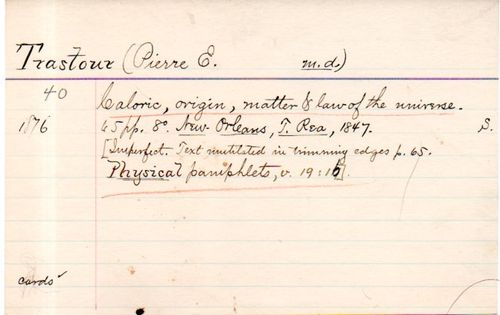

- And for those who are curious, this copy was the Library of Congress copy, and included the original hand-written card for the card catalog, itself a pretty thing:

Caloric itself has a place in the history of thermodynamics (mostly) as a gas, going from object to object as the transference of heat. It has a fairly strong history for 70 years or so, from the 1770's into the 1830's/'40's, and found interest in the works of the highest ranks of science in Lavoisier and Laplace and Black and others. It runs into modernity beginning with Rumford around the turn of the century (1799) and then dissipates with the work of Joule and Helmholtz and Clausius and many others, until it is mostly gone by mid-century. Caloric hung for a while in bits and pieces, though it is now remembered if at all for the "calorie" and for a line of ovens and stoves.

Trastour so far as I can tell doesn't have a seat at the history of science table--he doesn't seem to bump into anything interesting, though he does manage to say some outstandingly bad things about some of the biggest minds at that banquet. Here's an example of Trastour on Newton, appearing in The Round Table Review in 1865:

Trastour has little use for Newton, and doesn't seem to actually ever name the Principia anywhere. The chapter headings in the 1847 work are as follows: "Creation of the Universe", "Refutation of Newton's Principle", "Expositions of Principles", "Refutation of the System of Copernicus", Exposition of the Planetary World" (singular in the original), and "Truth".

Trastour proclaims in point #205 "One Only God, creator of all, from which all things come..." and "One Only Matter, Universal and Infinite, caloric, the primordial element, which has formed bu its different states of condensation the heavens, the earth and all things in nature". And so on, quickly deducing the non-existence of gravity and replacing it with the "peculiar manifestations" of the equilibriums established by caloric in bringing spinning bodies together.

In the end, for Trastour, it all comes down to three principles: love of God, love of mankind, and marriage. And "celibacy of thought" ("Whoever sets up the principle of celibacy, that immortal revolt of earthly ambitions against the divine thought, is not in the way of truth, and opens the road to disgrace and misfortune" (page 65, last paragraph of the work). That last has a bit of the sense of Precious Bodily Fluids from General Jack D. Ripper.

In a review of Trastour's work some years later, the author (signed "R") of the piece starts the article off in a way in which I thought he was going to do some serious damage to Trastour's theories. "I did not know the world contained one other dissenter from Newton's theory" R said, leading me to believe that the writer was going to have-at Trastour. But I read it to quickly, missing the "other" part, because as it turns out the piece is in support of Trastour and his world-altering ideas, and winds up being quite a hagiographic peon, which was surprising.

(The Round Table: A Saturday Review of Politics Finance, Literature ..., Volume 7, 1865)

I do very much like the title of the article, though.

Trastour returns to his cosmogony in 1875, writing in English this time, producing a booklet called The New Astronomy, which is 67 pages long compared to the original 65 of caloric. It is a different work--it jsut so happens that it is about the same length of his refuted first attempt, and it is also "a preface" to a greater work to come that never does. At the end of the book he does write on of the most glorious sentences probably ever written about caloric--well, if not the most glorious, it is at least probably the longest:

[Source: Google Books]

The search for the Universal often seems prompted by the ache for Something More. The World of Ten Thousand Things is not enough, and yet it's always too much for any single theory of Everything. There usually seems to be a kind of desperation in the effort, which probably accounts for the inevitable sense of fundamentalist fear and anger in the language of such writings. And that's my attempt at analysis for the day. You have an interesting collection of pamphlets, John.

Posted by: Jeff Donlan | 07 January 2014 at 01:03 PM