JF Ptak Science Books Post 2144

The Annalen der Physik, begun in 1799 and still going strong, is one of the foremost scientific periodicals ever published. Over the years the debut of revolutionary and significant ideas have made their first appearances in the journal--Gauss, Clausius, von Helmholtz, Doppler, and many many others, perhaps most famously by the four spectacular papers in Einstein's annus mirablis of 1905. The Annalen also famously re-published significant contributions by foreign scientists, their work seen in German for the first time in these pages. For many without French or English or Italian, it was the first time many German scientists read of Daguerre, Dalton, Cavendish, Volta, and so on--which was a big deal. [See this link for a collection of useful user's guides to the Annalen that are published elsewhere on this site.]

As a bookseller I've been lucky to own most of the Annalen from time to time, which has given me the real luxury of being able to go out to the warehouse and sit in the car with a few volumes of the Annalen der Physik, leafy through the volumes, breazily, grazing (as my friend Dr. Sam Koslov--late of the Hopkins APL and top-flight book collector--used to say), enjoying them and waiting for the great serendipities to occur. In all of this time a great sidelight in reading in the journal has been to appreciate the illustrations as they were intended, as well as images standing apart from their intended use, as found scientific art.

And since in our move I've decided to have a go at them once again, from the beginning, I thought that I'd start recording some of the most interesting/beautiful/odd/significant of them on this site.

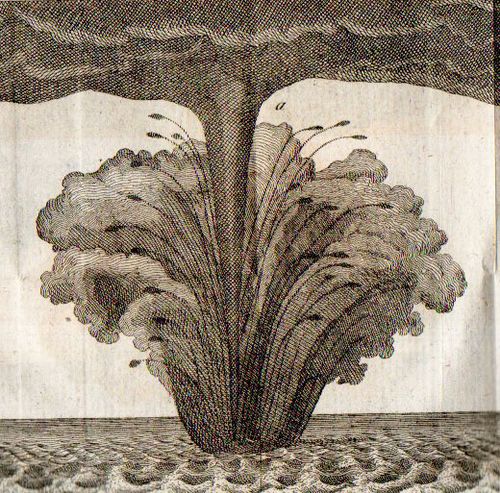

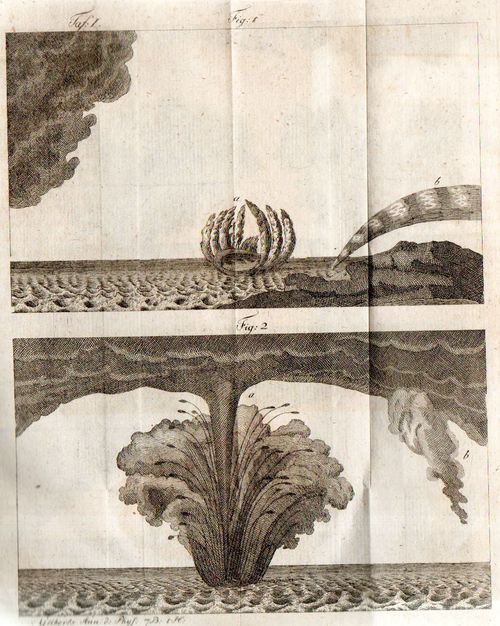

The first installation comes from series 1 volume 7, 1801, from an article about the work of Michaud on waterspouts, "Beobachtungen einiger Wasserhosen...". (The subject of waterspouts is an old one in scientific literature, most notably appearing in the scientific journal world in the Philosophical Transactions and reaching back to at least 1695, and Michaud's work on the subject extends to at least 1788. The use of waterspouts and tornadoes in art and in scientific literature in general is much older, with printed depictions of these creatures stretching back to the early 16th century. See this lovely and very useful site for a chronological display of tornadoes and waterspouts.)

The first installation comes from series 1 volume 7, 1801, from an article about the work of Michaud on waterspouts, "Beobachtungen einiger Wasserhosen...". (The subject of waterspouts is an old one in scientific literature, most notably appearing in the scientific journal world in the Philosophical Transactions and reaching back to at least 1695, and Michaud's work on the subject extends to at least 1788. The use of waterspouts and tornadoes in art and in scientific literature in general is much older, with printed depictions of these creatures stretching back to the early 16th century. See this lovely and very useful site for a chronological display of tornadoes and waterspouts.)

Michaud seems to set support the theory that waterspouts were electrical in nature, which even in 1788 seems to have been an idea that was losing favor.

The American scientist Robert Hare considered Michaud's observations on the physics of the waterspout in the American Journal of Science in July, 1837, and found hem to be, well, wanting:

But I'm after these images not for their place in the history of the explanation and illustration of tornadic activity, but for their artfulness inside and outside of their scientific merit and importance.

Comments