JF Ptak Science Books Post 2041

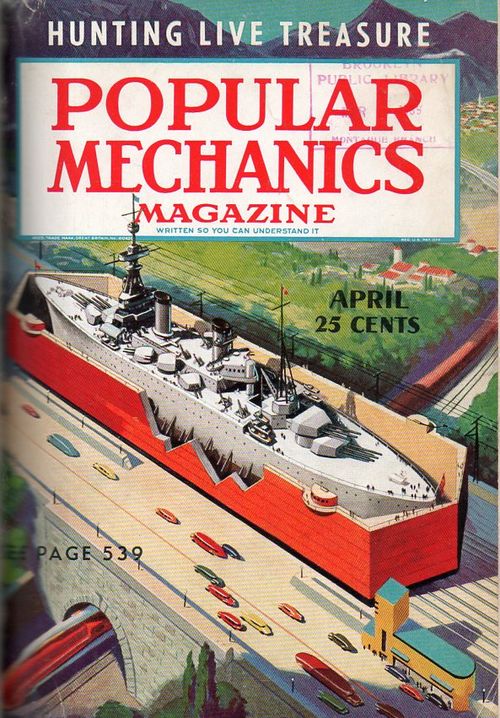

Full and massive and creative engineering dreams are the stuff of rich possibilities and the created demands of the created future. Sometimes they lead to the wonderful and essential, and sometimes they don't--pieces of these ideas may go places and lead full lives, but the overall big picture may have been just a little (or a lot) too big. The later may be the case for these ideas below--they include outlines for a trans-Atlantic ship tunnel (1927), the Cotherell/Eads 130-mile overland railway transport for transit across the Tehuantepec isthmus in Nicaragua, monumental masonry bridges supporting a car in which a battleship was driven, and others.

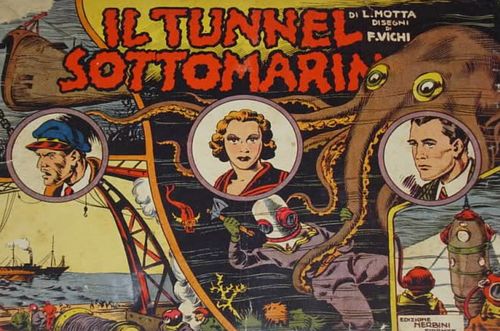

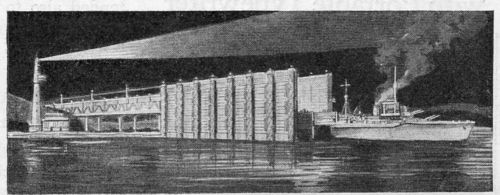

[Cross-section of the Atlantic Tunnel, found in Luigi Motta, Il tunnel sottomarino, published in Milan in 1927, and found while reading in the magnificent Dictionary of Imaginary Places by Alberto Mangule and Gianni Gudalupi/]This is the story of a mostly-submarine adventure, due to the work of a French engineer named Adrien Geant, who constructed a mostly-floating 4,700 km tunnel connecting Europe to America. Problems ensue and the tunnel fails, the resulting adventure of the survivors taking them to Atlanteja, which was a lost city constructed by the survivors of the lost city of Atlantis. Anyway, it is an interesting story of engineering, as the ideas behind the design of the tunnel were pretty good. The book was written by Luigi Motta (1881-1955), a man of active mind who wrote over 100 adventure/sci-fi stories.

(This isn't much of an image of the tunnel, sorry to say, but it is at least something from the book.)

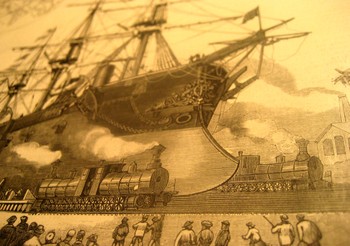

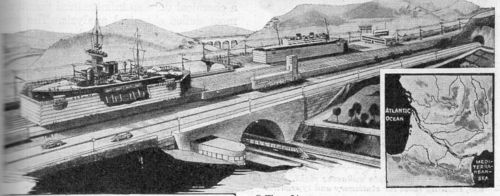

The Cotherell/Eads plan (from the Big Science post on moving Really Big Ships overland), which was described here earlier in this blog, was a vastly steampunk idea without the punk, "just" a lot of cobbled locomotives hauling big stuff for hours on multiple sets of tracks. It was a muscled idea for avoiding building the more-elegant Panama Canal:

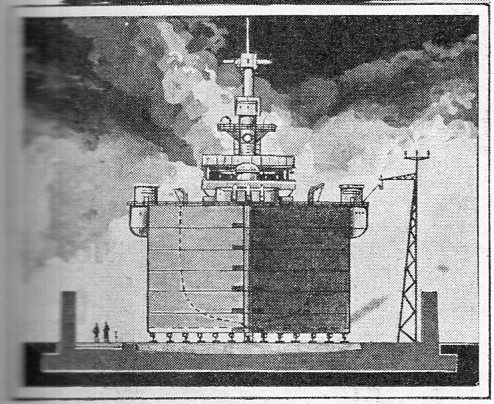

The ship-car bridge was certainly a very massive affair, supporting a 12-guns battleships as the thing made its way somehow across the span--not only that, there was a tunnel through the masonry bridge, which was also very tall:

The ship-car bridge was certainly a very massive affair, supporting a 12-guns battleships as the thing made its way somehow across the span--not only that, there was a tunnel through the masonry bridge, which was also very tall:

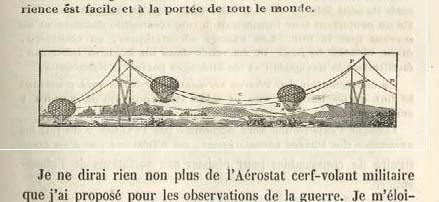

Then there is this beautiful and potentially entirely-not-useful engineering bit, adapting a system of bridge trusses that would somehow allow balloons to be guided along a prescribed path (from the Balloon Bridge post on this blog):

This short shelf-lived idea was that of Edward R. Armstrong (1880-1955), who in 1927 first published his plan for a series of 1200’x200’floating platforms for refueling and whatnot for transcontinental flights. These five-acre stations—named the “Langley” in honor of Samuel Pierpont Langley-- would be placed every 375 miles across the ocean. It doesn’t look like a very practical (or good) idea, but Armstrong received a $750,000 piece of development change from du Pont and GM, which was major dollars in 1929.Rounding out these ideas is the magnificent and aggravating Fitzcarraldo (a 1982 by Werner Herzog), in which a large river-going ship is hauled up-and-over and mountain as a short-cut for a long and miserable long-cut along treacerous and meandering South American waters.

In this presentation of Big Ideas, above, it is Herzog who actually did what he said he could and would do.

And a few other images of interest:

Comments