JF Ptak Science Books Post 335

Often

the reproduction of a print for popular consumption just doesn’t come anywhere

near expressing the flavor of the original.

This is definitely the case with Gaston Tissandier’s Bibliotheque des

Merveilles la Navigation Aerienne, l’Aviation et la Direction des Aerostats

(printed in

Often

the reproduction of a print for popular consumption just doesn’t come anywhere

near expressing the flavor of the original.

This is definitely the case with Gaston Tissandier’s Bibliotheque des

Merveilles la Navigation Aerienne, l’Aviation et la Direction des Aerostats

(printed in

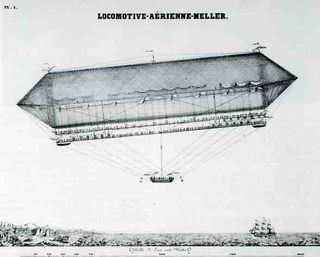

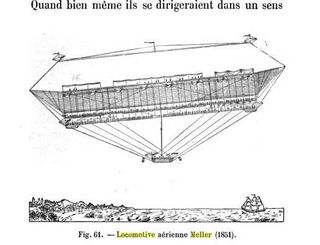

Paris in 1886), in which enormity of Propser Meller's (the younger) airship is

almost entirely lost. You do get the

idea of the size of the ship, but “bigness” is a weak constant, especially when

you look at the original print of the great ship, which turns that concept into

a more flavorful enormity.

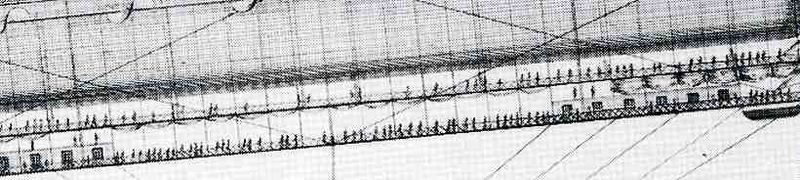

The Meller balloon--according to the scale at the bottom of the image--would measure a truly spectacular 200 meters/650 feet or so, and when you zoom in on the detail of the people aboard the ship the size becomes overwhelming. The print appears in Meller's rare work Des Aerostats, NAvigation areieene, Chemin de fer aerostatique....printed in Bordeaux in 1851, and of course the ship was never built, but it did serve as an intellectual forerunner of the more modern zeppelin.

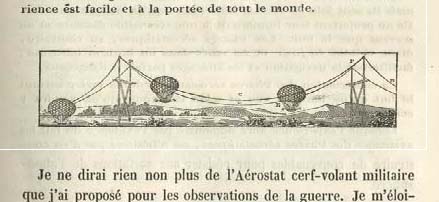

But the truth of the matter was that Meller was also very busy trying to figure out what balloons could actually do: Planning 600-foot-long airships (which would have been by far the longest vehicle of any sort ever built) is one thing, and one thing that was interesting but not terribly practicable in 1851; but he wrote elsewhere, in his Phare aerostatique (1854) that balloons could definitely be employed more easily with lesser goals but greater utility. For one thing a fixed balloon could be easily employed by the military of harbor control as a means for suspending artificial light sources. More ingenious and eyebrow-raising was another idea for a balloon bridge, which would’ve guided balloons across unbridgeable waters, shore-to-shore. It was certainly a bigger piece of thinking than a light source, but to me it sounds like a fairly plausible way of getting heavy loads and people across problematic bodies of water (and etc.) where bridges or boats would not work. In any event it seemed doable; at least far more so than the giant airship

As you can see, the miunutae detail of the original is lost in the reprint, and it is in the detail that the greatness of this airship can be found. .

The balloon bridge by Meller:

Some other works by Meller:

Projet de navigation aérienne (Imprimerie de Pollet ..., 1852)

À la marine (Typographie Plon frères, 1854)

Phare aérostatique.Paris:

Typographie Plon Frères, 1854.

*From Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, 28 August 1852 describing his 600’ airship:

Attempts are still being made towards aërial navigation. M. Prosper Meller, of Bordeaux, proposes to construct an aërial locomotive 200 mètres in length, 62 wide, and 60 high, the form to be cylindrical, with cone-shaped ends, as best adapted for speed. The outer case is to be varnished leather, which is to be filled with gas, and to contain five spherical balloons. A net, which covers the whole, is to support sixteen helices by ropes, eight on each side; and to these two galleries are to be attached, one for the machinery, the other for passengers. The affair looks well on paper; but there is little risk in saying, that the days of flying machines are not yet come, neither is the scheme for aërial railways—a series of cables stretched from one high building to another—to be regarded as any more promising.

Comments