JF Ptak Science Books Post 1918 Part of a long series, Blank, Empty & Missing Things

In the American motion picture industry, the sound technician position did not exist in 1927; in about 1000 days it would be almost as important as the director. 1927 marked the first year of the synchronous, simultaneous sound-on-film motion picture, with the first commercial production appearing in 1929. (The history of motion pictures with sound is pretty complex for the 1920's; suffice to say that there were different attempts on synching separately filmed and audio recordings which was a difficult beast to master, and virtually no one did; the winning attempt at introducing sound into the movies had to be sound-on-film so that there would be simultaneous play of sound/film.) Prior to this, all dialog, all sound effects, were confined to the mind of the viewer, though there was sometimes live musical accompaniment. Two years later, sound was in, and silence (as an absolute given) was out.

The impact of sound had an overwhelming effect on the medium—not only because the actors could speak, but because they could also act within the subtleties of now being heard. Whereas just the other day actors had to pantomime hearing different sorts of sound, or act in such a way that the audience knew that they were weeping—much had to be visually over-acted to support the lack of actually being able to hear things. Once sound was incorporated, the dramatic range of actors advanced exponentially. Of course there was also everything else outside of voice that could be incorporated by the director: ticking clocks, advancing footsteps, thunder, sirens, heartbeat, a soft wail, a chortle, an echo. And silence could now be used to its true effect, its importance rediscovered.

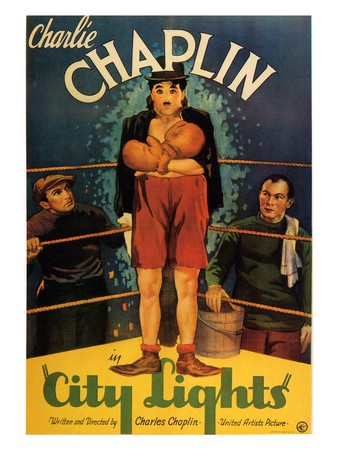

The last, true silent film came in 1931, with Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. Chaplin acted/directed/produced the film, which, interestingly, was not really, altogether, absolutely, a “silent” film. The movie—which directors Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tartofsky both selected as their fifth film in their top-ten all-time movie lists—actually used idiosyncratic and unintelligible sounds as speech in a spectacular salute to non-speech speech. Chaplin was one smart man.

The advent of sound curiously silenced the careers of some of the great silent-era actors whose voices were really just beyond reach and the range of the enjoyable. Clara Bow bowed out as a result of her deep Brooklyn accent, as did John Gilbert for his very high-pitched voice, and many others. Such are the few ironies that came along with this rich technical advancement, small price to pay for a piece of the future.

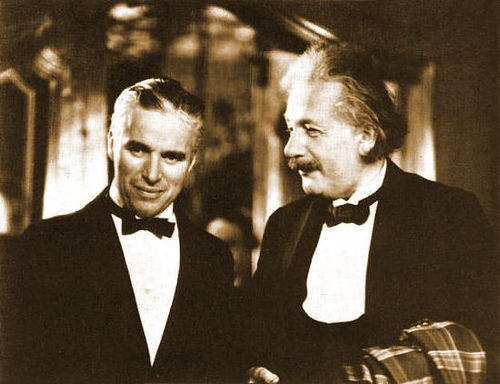

(Chaplin and Einstein at the premier of City Lights.)

Comments