JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 1921

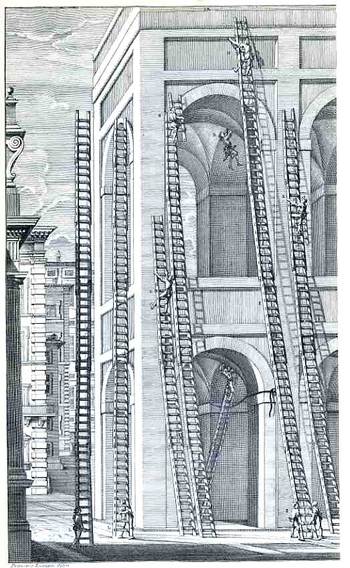

This gorgeous, near-pre-Dadist image belongs to Niccola Zabaglia, who published the engraving in his book Castelli, e ponti di maestro Niccola Zabaglia con alcune ingegnose practice, e con la descriziojne del trasporto dell’obelsico Vaticano, e di altri del cav. Domenico Fontana, in Rome, in 1743. This is the literal and absolute height of pre-modern, pre-mechanized building construction in the soaring Roman Baroque, ordained by “maestro”, the master, Zabaglia (1664-1750), a spectacular (and necessary) proponent of practical mechanics as applied to the building trades. Among the “Castles” and churches and bridges alluded to in the title of his book, Zabaglia was responsible for affecting the maintenance and repair of St. Peter’s (more particularly to the basilica and the vault)—specifically, he had to figure out how to get the workmen and materials into place, and into very difficult and very high places, without damaging or destroying any of the existing decoration, artwork, sculpture, frescoes, and so on. This was no easy feat to perform back there in the dim, 265+ years-ago pre-electric pre-power past, with enormous technical and operational difficulties, and Zabaglia accomplished this was superior affect, devising complex and elegant moving and stationary scaffolds, hoisting and holding mechanisms for the ladders, and much else. He did just beautiful work, and he is a patron saint in the history of repair.

Ladders and scaffolds were important of course but were among the least of Zabaglia’s numerous accomplishments and inventions—they were so plentiful and useful that two Pope Benedicts ago (Pope Benedict the 14th) ordered their publication with actual teams of artists and engravers performing specific tasks.

It cannot be left unsaid that Zabaglia's portrait as the frontispiece to his work presents almost without a doubt the most approachable, humane and amused representations of a major engineer/artist/artisan published in almost any work of the 18th century--I mean, the man just looks so happy in his work. There he is, surrounded by the tools of his trade, in work clothing and a scruffy hat, and needing a shave, and just looking as pleased as can be. No?

But to the ladders: the examples in the engraving above are certainly massive. The ladder in the middle I would say must be 70' tall (judging that it has 60-odd rungs and that there are 5 rungs to the men who are stabilizing it at bottom), and since they're made of a good hardwood (to prevent bowing that must occur in a lesser material), the things must've weighed a good amount. And offhand I'm not exactly sure how they raised them. I can't see the tops of the building, but I would assume that there was a pulley up there. I hope. In any event, the ladders and their found geometries are gorgeous things. Also, I would guess that in the very long histories of ladders (a ladder appears in a cave painting from 10,000 BCE and also appears in one of the very first photographic experiments) that these must've been among the high points in ladder construction.

But to the ladders: the examples in the engraving above are certainly massive. The ladder in the middle I would say must be 70' tall (judging that it has 60-odd rungs and that there are 5 rungs to the men who are stabilizing it at bottom), and since they're made of a good hardwood (to prevent bowing that must occur in a lesser material), the things must've weighed a good amount. And offhand I'm not exactly sure how they raised them. I can't see the tops of the building, but I would assume that there was a pulley up there. I hope. In any event, the ladders and their found geometries are gorgeous things. Also, I would guess that in the very long histories of ladders (a ladder appears in a cave painting from 10,000 BCE and also appears in one of the very first photographic experiments) that these must've been among the high points in ladder construction.

Comments