JF Ptak Science Books Post 1786

It is intriguing to see ideas are communicated when drawn as a series of events on a single piece of paper--a single-panel, progressive illustration showing the sequential development of an idea. This thought struck me while looking at some of the work of J.J. Grandville (above, "Les Metamorphoses du sommeil", from his book Un Autre Monde, a proto-surrealist work printed in 1844) ) and caused me to think about how old this idea might be, how far back it stretched into the sciences and literature. And right now, I really don't have the answer.

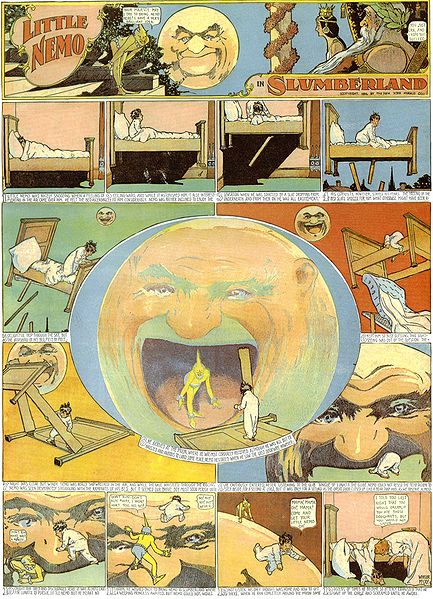

Again, what I'm thinking about is a single-sheet describing an action or thought--not like what might be the earliest example of the "comic book" the Histoire de M. Vieux Bois (1827) by Rodolphe Toepffer (Geneva, 1799–1846) but more like Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McKay (the following example from 1905). The difference between the two in composition is simply that McKay in his Sunday comics efforts would develop the story on a single sheet of paper, so that you are in a way watching the story unfold as a motion picture would; and in the case of Toepffer, the story is told more in a conventional graphic novel way--in a book over dozens or hundreds of pages, with one illustration per page. (I wonder about including Egyptian and Mixtec hieroglyphics, but I don't think that they apply.)

What seems like an early ready-made example of the sequential imaging of an idea on one piece of paper might be from the great William Harvey's De Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (On the Movement of the Heart and Blood in Animals), which was printed in 1628, and which in an iconic display shows Harvey's demonstration of blood operating in a closed system, and circulated by the heart, and undergoing a "a motion in a circle".

[Source: this image from Exercitationes Anatomicae, De Motu Cordis & Sanguinis Circulatione.. Rotterdam: Arnoldus Leers, 1660..]

Okay, well, this is actually two plates, so I'm fudging. But it does put me in mind of early (say, 16th and first-half 17th century) anatomical atlases and how some of them displayed (for example) the anatomy of the eye by doing a paper dissection, and confining it to a single sheet.

There are no doubt many examples from early books in the history of technology, the following image of mine ventilation coming from Georgius Agricola (1494-1555) De Re Metallica (On Metals), and printed in 1556:

![[Plate from De re metallica showing three methods of ventilating mines]](http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/cph/3c10000/3c10000/3c10300/3c10346r.jpg)

[Source: the Library of Congress, here. There are many more examples of this sort of information display in this work alone--there are 291 illustrations over the book's 586 pages, and many will fall into this category.]

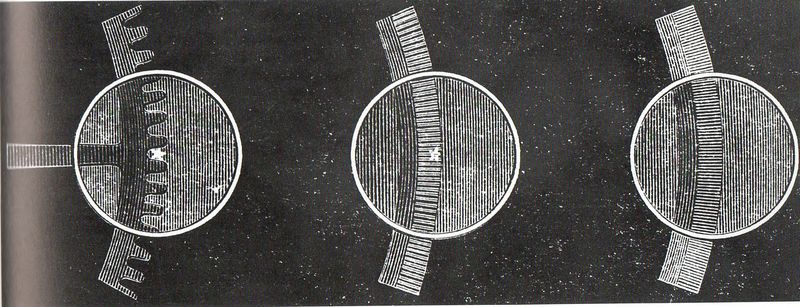

Armand Fizeau (1819-1996) employed a simple and elegant (and very important) series of three images in his paper on the measurement of the speed of light (1849):

( The way the apparatus worked was simple and powerful: Fizeau observed a light through an optical apparatus with a rotating toothed gear between observer and the entry of the light source; a mirror that was more than 5 miles away reflected that beam back through those same geared teeth of the disk. The disk could be made to rotate at specific speeds, the object being to calibrate the disk to prevent the light from going through the teeth of the gear to the mirror and then back again through the same gap. The point at which the dot o flight disappeared could be easily calculated and the speed of light extrapolated from there--which Fizeau estimated to be 313,300 Km/s or 194,410 miles/second. (In 1850 Foucault replaced the toothed gear with a mirror and produced a more accurate estimate of 185,093 miles/second, which in fact turns out to be very close to c. ))

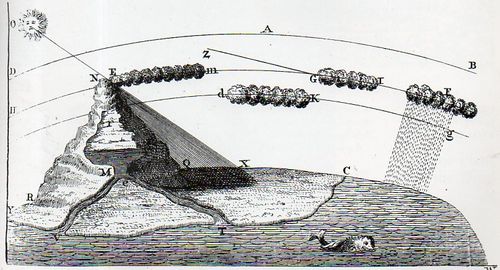

A good example from the meteorological world might be seen in Stephen Switzer (The Practical Husbandman and Planter, 1733) with his display of the water cycle:

There are good examples of a developing story and allegorical series told in the single panel Medieval and Renaissance paintings (where, say, we see the life story of a saint portrayed around the outer reaches of an image showing a backdrop to the essential biography of the painting's main character), as well in the complex images that are imbued with a big story line, as in some of the work by the Brugels and Bosch. Also there are narrational objects such as the bronze doors from St. Mary’s Cathedral, Hildesheim (c.1015) which displays a history of the world from the creation to the passion of Christ:

In another vein, the work of William Hogarth in the Analysis of Beauty series (1753) may also fit this category:

as it is Hogarth's intention to display the development of a certain aesthetic over a number of different images, though each individual engraving stands on its own.

These are only the first notes on this idea of looking at conceptualization as it appears on a single sheet/plane. I hope to be returning to it as more examples present themselves.

Comments