JF Ptak Science Books Post 1778

For a painter to make a point of looking for poetry in the conception of a picture is the surest way for him not to find it.--C. Baudelaire.

The qualities of being indistinct certain have their places, though those places are relatively rare in areas like the engineering of dam or bridge building, or in the rules of a game like chess. Over time these qualities have certainly changed and manifested in different fields, say, for example, in literature and art--particularly in art.

This brings us to Melville and Turner. It is a curious thing to see Herman Melville's collection of J.M.W. Turner engravings, to see what the man collected and what might have drawn him to those particular pieces. After all, Melville was a necessary collector--he needed things, sometimes needing them more than his family needed things, like food--and so to see the visual items that were "necessaries" is very interesting.

And when you look at the engravings of the Turner paintings in most cases they bear little resemblance to the original. As a famous and respected, highly admired artist for more than 40 years, Turner's early works can also be considered famously 'indistinct". As a matter of fact, that was a major concern of some of the great artists and critics of the time, viewing some of Turner's beautiful pre-pre-Impressionist works. (His very highly Impressionist works reaching back to just before 1800, very well in advance of Boudin and Manet, Corot and Millet, Daubigny and Courbet, and the rest.) People didn't quite know what to do with the "indistinct" shorelines in his naval/maritime works, or the suggestions of people, or the fantastic mystical skies of deep foreboding and threat communicated with emphasis on color and suggestion more so than accurate physical representation.

Robert K. Wallace takes on the issue of this relationship between the literary and artistic giants in Melville and Turner, Sphere of Love and Fright (University of Georgia Press, 1992) and discusses it very fully over 635 pages. I was interested to see the list of the Turner engravings collected by Melville and of course everything else that went along with that. Wallace notes John Landseer's reaction to one of Turner's earlier and not tremendously impressionist works (Sheerness as Seen from the Nore, which is a great title in and of itself) was very guarded, saying that the shorelines "are little more than threads in the distance", and writing in 1808 of The Confluence of the Thames and the Medway of the painting's "indefinity", and of his doubtfulness of the "indistinctness" of Richmond Hill and the Bridge". After all, even the pre-impressionists really wouldn't begin to make a full appearance for a few more decades, and the subject of suggestion of form in painting rather than their depiction was a very major issue.

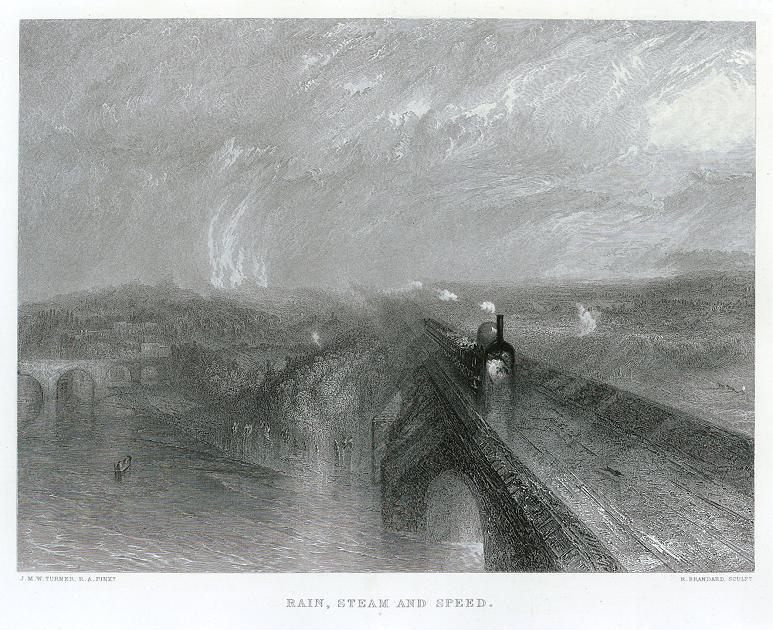

Turner would move more deeply into his expressive creativity as he grew older, producing work after work of high impressionist qualities, such as, for example, Death on a Pale Horse (1825-1830), Staffa, Fingal's Cave (1832) and

[Staffa, Fingal's Cave.]

[Death on a Pale Horse.]

Rain, Steam and Speed (1859). Wallace relates a great story of the first Turner painting making its way to the United States, coming by way of a purchase by James Lenox of the Staffa painting, arriving here in 1845, already very deep into the career and life of Turner (1775-1851). When it arrived and unboxed, the new owner Lenox was extremely surprised by the suggestive qualities of the painting, which to him "appeared so indistinct throughout" (Wallace, page 74). Lenox wrote Turner with his observations, when he wondered if the trip by sea had actually done something to the paint of the picture, rendering its detail obsolete. Turner replied that the "indistinctness is my fault". Lenox was certainly seeing something new--it was something revolutionary in art and vision, and not a spoilation by salt and sea.

So I wondered about Melville's collection of Turner, and how the engravings might differ from the paintings, and how in general the work would be more tailored for a general audience, with the great "indistinctness" of the works lost in incised lines on copper and steel. Did Melville know the of the differences between the mass produced item and the original painting? Or did that matter, at all, particularly if Melville was looking at the ships and other parts of the images that reminded him of his own experiences real or imagined, and that his brain would fill in the detail as necessary? (And there are certainly differences, as we can see below:)

Another question is whether or not Melville would have known the difference, or if he was even aware of the great idea of indistinctness existing in Turner's originals, and what this new way of painting would come to represent. At this point, I'm not sure, and I'm not sure that I need to be sure, at all. Perhaps the issue is best left to question, being left to its own indistinctness, left for interpretation and imagination. I think that is good enough for me, right now.

Other examples of Melville's collection of Turner images compared to the originals:

Comments