JF Ptak Science Books Post 1733

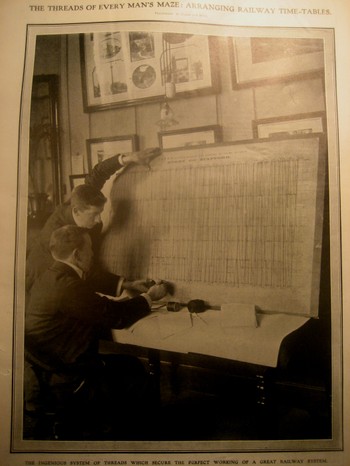

It is astonishing sometimes to think about how much was accomplished with so little. This photograph, found in the 6 June 1908 issue of the Illustrated London News, entitled "The Threads of Every Man's Maze: Arranging Railway Time-Tables" (sub-titled "the ingenious system of threads which secure the perfect working of a great railway system") is just such a case in point of wonder. Each section of the board represents one hour, top to bottom; these are further subdivided by thinner lines representing 5-minute intervals; the horizontal lines representing the distances between stations. And the guys in the foreground are keeping the whole thing up-to-minute, using string and tacks.

It is astonishing sometimes to think about how much was accomplished with so little. This photograph, found in the 6 June 1908 issue of the Illustrated London News, entitled "The Threads of Every Man's Maze: Arranging Railway Time-Tables" (sub-titled "the ingenious system of threads which secure the perfect working of a great railway system") is just such a case in point of wonder. Each section of the board represents one hour, top to bottom; these are further subdivided by thinner lines representing 5-minute intervals; the horizontal lines representing the distances between stations. And the guys in the foreground are keeping the whole thing up-to-minute, using string and tacks.

This was the British Empire at about its loftiest heights, with a spectacular internal railroading system, kept all in line and on time and correct with the help of heavy thumbs. Can you think of a better way to display all of this complex data (with 1910 technology) in real-time so that it is all intelligible--and to be so instantly? I can't. This was just sheer, simple, brilliance.

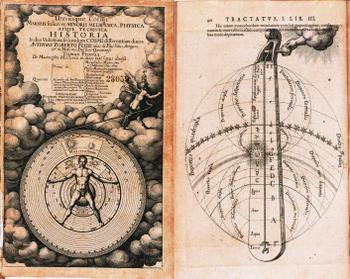

I know, I know, this is actually "thread", but so it goes. If you elongated and strengthened this concept just a bit you'd come up with rope and wire, and chains--the most simple metallic form of which was used by surveyors for hundreds of years to help map our earth. And I won't even get close to the String Theory stuff here, or stringed instruments--but if I did, I would want to talk a little about perhaps the ultimate string/cosmology image in the history of science, which would be Robert Fludd and his fantastical thought-experiment called "Monochordum mundi". from his Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris metaphysica, physica atque technica historia, printed in 1617.

Fludd makes an elaborate and beautiful stab at understanding the deepest aspects of an imagined supramusical relationship between the order and rationality and mathematical aspects of music and the functioning of the universe—based on sound itself. These ideas come up time and time again, most visually pleasing in Fludd, but most dramatically argued by Johannes (Harmonicae Mundi, "Music of the Spheres") Kepler. But Fludd trumps with god’s graphical intervention.

Fludd makes an elaborate and beautiful stab at understanding the deepest aspects of an imagined supramusical relationship between the order and rationality and mathematical aspects of music and the functioning of the universe—based on sound itself. These ideas come up time and time again, most visually pleasing in Fludd, but most dramatically argued by Johannes (Harmonicae Mundi, "Music of the Spheres") Kepler. But Fludd trumps with god’s graphical intervention.

The hand of god makes an appearance here as it adjusts the magic monochord of creation--a Pythagorean monochord of two octaves which are then divided into harmonic intervals. But god's hand is definitely there, doing some sort of adjustment (or perhaps even holding the slipping peg in place?), which is actually a little bit late in the history of the mechanical universe being turned by the hand of the creator, with the hand actually depicted doing the job. In general the hand stopped making appearances by this point in the history of science, but did manage to linger on in the work of Fludd.

Comments