JF Ptak Science Books Post 1715 [Part of the History of Dots series.]

I wanted to land this post (the title of which is nearly as long as the article) on this little island in a wide sea of similar islands in the complicated 18th century history of embryology. Where we came from and how living things developed really wasn't very clear at this time, and really wouldn't be until Karl Ernst von Baer discovered the human ovum in 1827.1

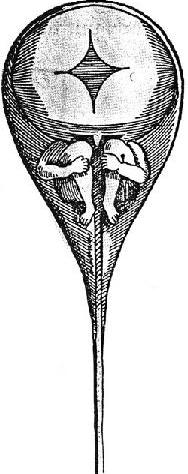

The issue of the ovaries as ovens--of homunuclus and palingenesis and epigenesis, the imaginary male-dominant anatomy of reproduction–was pretty much somewhat solved by the beginning of the 19th century. Or at least the homunculus, the tiny but perfectly formed miniature human traveling along in sperm, was. This character is pictured here, riding in the squinty-eyed imagination of researcher Nicholas Hartsoeker2, who desperately wanted to see the thing, I think, and which found itself published in his book Essai Dioptrique in 1695. Spermatozoa was discovered earlier by the great Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) and which was finally confirmed in its fertility hypothesis by Lazzano Spallanzani, who also happened to be an ovist, thinking that each egg contained a pre-formed embryo).

The issue of the ovaries as ovens--of homunuclus and palingenesis and epigenesis, the imaginary male-dominant anatomy of reproduction–was pretty much somewhat solved by the beginning of the 19th century. Or at least the homunculus, the tiny but perfectly formed miniature human traveling along in sperm, was. This character is pictured here, riding in the squinty-eyed imagination of researcher Nicholas Hartsoeker2, who desperately wanted to see the thing, I think, and which found itself published in his book Essai Dioptrique in 1695. Spermatozoa was discovered earlier by the great Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) and which was finally confirmed in its fertility hypothesis by Lazzano Spallanzani, who also happened to be an ovist, thinking that each egg contained a pre-formed embryo).

The woman as a simple baker of a gift of preformed life was a medical belief that helped perpetuate the supposed inferiority of women, and that the woman’s part in the procreative process was a simple oven. It was a difficult image/belief to resist, persisting well into the 19th century. But there was another side of this debate as well, and that was that woman didn't need the male sperm to proceed with the process of conception, with some scientists believing that coition had nothing whatsoever to do with the process. And so there were battle lines drawn in the primordial embryological sand of the 18th century, each demanding a sex-dominant role in procreation.

And if sperm contained a perfect, pre-formed human being, waiting to be planted in the oven of woman, what happens to all of those-pre-forms in the sperm that went "unused"? I imagine that if you were an 18th century pre-formationist that this would be a tricky and very uncomfortable question. If you could put on special sperm-specs that would allow you to see "ejected" and "unused" sperm in the same sort of ways in which we can see non-visible light, that, well, you might want to watch your step and avoid smashing a fully-formed human being that had the potential of living for weeks on its own with the benefit of anything else at all. I have to admit that even for me this makes the picture of this Earth not very savory. The author of "A Brief History of Sperm" at SeductionLabs.org points out that at least one English country doctor, James Cooke, thought that this ejecta "might not die", at all,

"... but ‘live a latent life, in an insensible or dormant state, like Swallows in Winter, lying quite still like a stopped watch when let down, till [they] are received afresh into some other male Body of the proper kind’."--from SeductionLabs.org, in its "A Brief History of Sperm".

It sounds a little like embryologico-guerrilla warfare.

In the middle of the sides drawing themselves up for battle, choosing male- or female-dominant mechanics of procreation, or a combination of both, were the supra-ovists, who claimed that in this mess that every human who would ever be born on Earth was already present in the ovum of Eve. There were some who tried to calculate the figure of how many people that ovum contained, but like the creation timeline of Bishop Wilberforce, the numbers were open to severe self-definign interpretations.

It is interesting to note these debates, though, because they weren't really finally settled until just three generations ago. (Or four if you're much younger than I.)

Notes:

1. von Baer published his discovery in his Epistola de Ovo Mammalium et Hominis Genesi (Leipzig, 1827), followed by his two-part Ueber die Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere in 1828 and 1837 on the history and evolution of animals. The original paper did not catch on, immediately, and took some years to be established. There was actually a paid competition going on in Europe at this time for the purpose of finding the ovum, and although aware of the award and thinking he had found the "prize", von Baer was not well-doisposed to the idea of the "race", and so really didn't participate. Jean-Louis Prevost (1790-1850) and Jean-Baptiste A. Dumas (1800-1884) also came to the conclusion that the "animacules" in the semen were responsible for fertilization. The deal wouldn't be solidified until Oskar Hertwig actually observed the fusion of the male and female material in the ovum of a starfish in 1876.

2. Hartsoeker ("heart seeker") (1665-1725) was a microscopist of high order in addition to being a physicist and a medical doctor, never actually saw this thing in his investigations--he iterated that the little person must be there. But he never did say that he observed it.

Comments