JF Ptak Science Books Post 1718

[Part of this blog's series on the History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things: Names.]

There was a brief point in Charles Darwin’s publishing life when the old (then young) man got stiffed. Darwin’s magisterial contribution to Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of her Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1S26 and 1836…, (published in 1839) appeared in the third volume, (by far and impossibly away the "money" volume), and was issued without his name on the title page, which as it turns out was okay by the standards of the day. The real oddness turns up in the publisher’s ads that appeared in the later issues of those volumes in late 1839 for what would be a separately-issued volume of Darwin’s contribution (Journal of Researches into the Geology…), where again there was no mention of the author’s name. (Captain Fitz-Roy, the man whose name adorned those early volumes, was the Captain of the Beagle a man with problems and some very interesting and early meteorological ideas; but both would be dead to one another soon enough.) The recognition element was dismissed very quickly though when the work was actually published—his name was in the book but not in the advertisements.

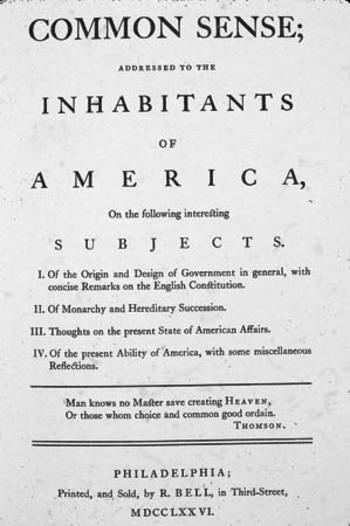

This is really just a little fly in the ointment though in the publishing history of major scientific works--anonymous literature (or in the Darwin case, really, seemingly purposely forgotten) isn’t that deep and long in the sciences, especially when you excuse ancient and middle-Renaissance period efforts. Certainly the sciences don’t compare with other disciplines, where works by anonymous or pseudononymous abound. The history of world literature ancient and modern abounds in silenced or self-silenced authors—there is even a four volume encyclopedia to help you identify the unidentified. . Political and religious work are also particularly heavily laden with unattributed or disguised efforts—the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist Papers are of course both anonymous (and of necessity), as was the most beautiful work of Voltaire. The Declaration of Independence, on the other hand, and also of necessity, was not. What is that they say? Anonymity is the best defense against the tyranny of the majority”? It still feels a little Orwellian to see the unattributed source in the newspaper or read an anonymous editorial. On the other hand Thomas Paine’s sublime On Common Sense may not have made it into print if its author had been required to identify himself.

Art is perhaps the longest-lived area of anonymous work, the signed canvas being a relatively recent invention. There are thousands of years of unknown hands and eyes represented in millions of works, but really we only get solid confirmation of the intellectual origin of a work through the invention of the ornament of the signature, and this just within the last 500 years. And even after this defacement begins to appear there is still a relatively stout history of semi-anonymous works coming from painting studios doing work “in the manner of ____”. Of course there were other considerations at play here, what with guilds and patrons and all—the artist was one person in a lengthy bureaucratic trail of aesthetic production.

Anonymous seems to come more into play in our present culture via the need for a place holder—when tallying and accounting the death of unknown people, for example, the name “John Doe” or “Jane Roe” is used (in the U.S.) to take up the forever empty space calling for The Departed’s name. (Our most famous “Jane Roe” is Norma McVorvey of Roe v. Wade; I think the Gary Cooper still ranks the highest for the male equivalent.)

Anonymous seems to come more into play in our present culture via the need for a place holder—when tallying and accounting the death of unknown people, for example, the name “John Doe” or “Jane Roe” is used (in the U.S.) to take up the forever empty space calling for The Departed’s name. (Our most famous “Jane Roe” is Norma McVorvey of Roe v. Wade; I think the Gary Cooper still ranks the highest for the male equivalent.)

Something has to go there, and so it is. The practice of using such names is actually pretty old, and is practiced worldwide. (see HERE for an entertaining look at multi-cross-cultural “John Doe” equivalents.)

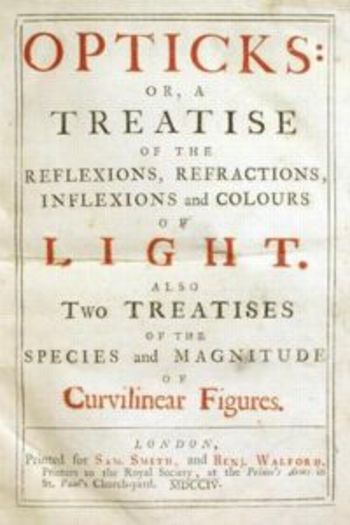

And now that I’ve had some time to think about non-Darwins examples from the sciences, I’m a little stumped. Robert Boyle is a good example, what with more than a dozen of his works (at least according to John Fulton’s bibliography) were published without his name carrying the title page-but these were the philosophical and political works of a great scientist, and not scientific. Same too for Pascal, who wrote his Pensees undercover—and again, not scientific but by a scientist. Isaac Newton published his fabulous Opticks without his name on the title and in fact only used his initials (sort of) in the preface as his personal identifiers. He was though in 1704 when this book was published a decade’s-long acknowledged super genius, and I’ve never been very comfortable with any explanation over this unNewtonesque shyness for his big optics book.

Opticks without his name on the title and in fact only used his initials (sort of) in the preface as his personal identifiers. He was though in 1704 when this book was published a decade’s-long acknowledged super genius, and I’ve never been very comfortable with any explanation over this unNewtonesque shyness for his big optics book.

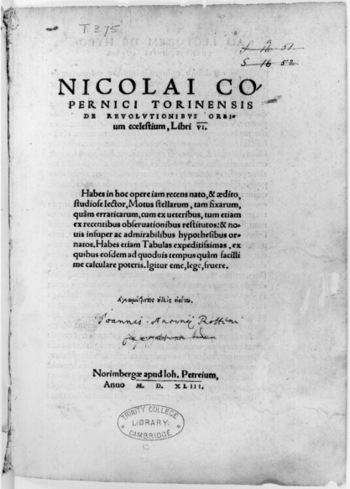

That leads us lastly to Thomas Malthus, who really did publish the first printing of his massively important Essay on Population without his name—it would make an appearance soon after, though, in the second edition of this contentious work making the first edition of this great near-scientific work one of the most influential anonymously published science books of the last 250 years. Laying Malthus aside though and lifting the time-veil for just a peek, the best example in this genre turns out not to be an example at all. Copernicus was the ultimate anonymous author of a scientific work because he didn’t publish it—fearing reprisals for his horrifically challenging and revolutionary work, Nicolas waited until he was b asically dead to have his effort put into print. Then, once he was safely assured of his snug bed with the worms, free from fear of all anxiety and moral espionage, did he see the work brought to public display—with his name very boldly displayed on the title page.

asically dead to have his effort put into print. Then, once he was safely assured of his snug bed with the worms, free from fear of all anxiety and moral espionage, did he see the work brought to public display—with his name very boldly displayed on the title page.

Comments