JF Ptak Science Books Post 1651

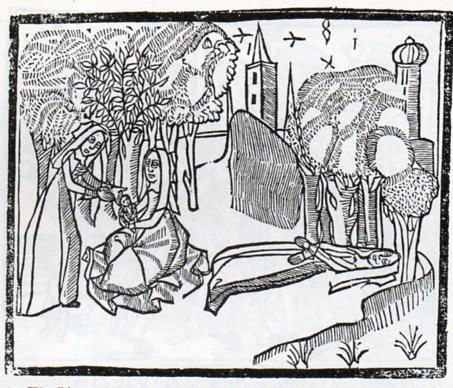

Sir Thomas Mallory (c. 1405 – 14 March 1471), translated and compiled a collection of mostly 14th century romances regarding King Arthur known and published as the Le Morte Darthur/Le Morte d'Arthur. It was first published by the great William Caxton in 14851and became quite popular, being reprinted with additions and corrections in 1498 by William Claxton and then again by Wynkyn de Worde (in 1529). It is, in its way, beautifully illustrated, or at least interestingly illustrated--I can't really say for sure if the woodcuts were done with great care or not. But their effect is significant, and, whether naive or not or careless or not or simply at the artistic limit of its executor or not, the images do have their own peculiar beauty. One that struck me in particular was this,

the "floating river", an out-of-perspective element of a very stationary world, a controlled chaos-ness in a static landscape. I'm not sure what is going on with the trees, if the blankness is a part of reflected light, or if it is a representation of spaciousness between the limbs, or if they are simple wormholes in the woodblock. Everything in the image seems to have its own sphere, locked into their own environment, existing apart from everything else.

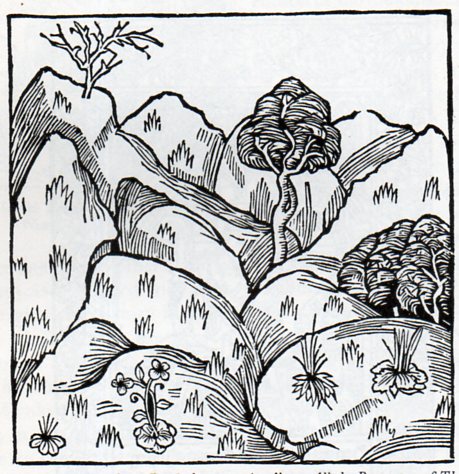

I see the same issue with many other such works, bits dropped into place in a scene or landscape, all making their way into the viewer's mind on their own, not really a part of a cohesive whole. This may have been the intent, or again it may have rubbed up against the outer limit of what the artist (and their tools, and medium, etc.) was able to actually produce. Here's another example:

Its another lovely, lonesome image of separates from the beautifully-named book by Bartholomaeus Anglicus All the Properytees of Thyings, which was published in Westminster in 1495 (and also known as De proprietatibus rerum, also translated as On the nature of things, or On the properties of things), and which was originally written around 1225). The book was a bestiary, a marvelous encyclopedia, a collection of all things as known in the 13th century--it would be interesting to represent all that is know today and compact it into a workable, logical, usable (printed !) book of a thousand pages. The question of organization of knowledge would be the key, of course, and how to make one flow to another complementarily as practicable...it would be an interesting project (for someone else) to try and arrange the basis of human knowledge in a finite space like that. The author of the book above organized his work as follows, in 19 books: "god, angels, (including demons), the human mind, or soul, physiology, of ages (family and domestic life), medicine, the universe and celestial bodies, time, form and matter (elements), air and its forms, water and its forms, earth and its forms including geography, gems, minerals, and metals, animals, and color, odor, taste and liquids." The 2012 variety of categories would be somewhat different.

Notes:

1. This period, from say 1494 to 1525, was one of great creativity. For example: 1494, Pacioli: Everything About Arithmetic, Geometry and Proportion; 1498, Leonardo da Vinci: Last Supper; 1500, Michelangelo, Pieta; 1504, Michelangelo: David and Bosch Garden of Earthly Delights; 1505, Leonardo Mona Lisa; 1506, work begun on St. Peter's Basilica; 1508-1512 Michelangelo paints the Sistine Chapel; 1511, Erasmus, Praise of Folly; 1512: Erasmus, De Copia; 1513, Machiavelli The Prince; 1516, More, Utopia; 1517, Start of the Reformation.

Some samples of other bestiaries (compiled by The Medieval Bestiary):

Hrabanus Maurus : De rerum naturis

Isidore of Seville : Etymologies

Lambert of Saint-Omer : Liber floridus

Brunetto Latini : Li Livres dou Tresor

Jacob van Maerlant : Der Naturen Bloeme

Konrad von Megenberg : Das Buch der Natur

Thomas de Cantimpré : Liber de natura rerum

:

:

Comments