JF Ptak Science Books Post 1644 [Part of the Series on the History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things.]

"Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we've got our brave Captain to thank"

(So the crew would protest) "that he's bought us the best-

A perfect and absolute blank!"--Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark.

[This post fits perfectly in our History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things. Ditto for the series on The History of Lines--making this a great confluence for a History of Blank and Missing Lines (in the History of Nothing series).]

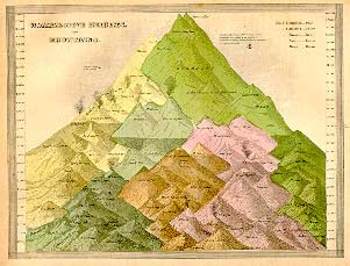

For all of the brilliance of all of the cartographers and map makers who have drawn a line in the sand or strung a strand of quipi or drawn a celestial rendering on a cave wall or imagined the Americas in 1504 or ventured out and away from the Medieval T-maps or drew maps of other worlds or fashioned spiraling maps of Hell, I think the maps I most like are maps of imagined places. Of course I enjoy the extremely rigorous and steadfast maps (like those of the German Stieler Company of Gotha who for a hundred years routinely drew the most detailed maps in a particular scale than any other mapmakers in creation—you know, the big maps of the U.S. that would locate minute places like Truman Capote’s “out there” town of Holcomb, Kansas) and of course maps of the solar system and galaxy and universe (as knowledge expanded and collapsed and expanded again). And of course there are the representational maps showing the comparative heights

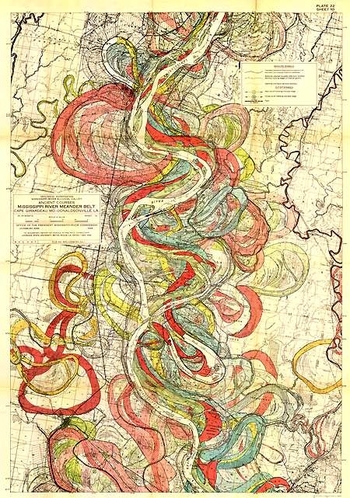

of mountains and lengths of rivers, or the grouping of all the world’s lakes, or the divorce rate map of the United States at Centennial, or the heights at which different sorts of trees are found, or geological speculations on the thrust of the Appalachian chain, or the wanderings of the course of the Mississippi River (below), and other hosts of things.

of mountains and lengths of rivers, or the grouping of all the world’s lakes, or the divorce rate map of the United States at Centennial, or the heights at which different sorts of trees are found, or geological speculations on the thrust of the Appalachian chain, or the wanderings of the course of the Mississippi River (below), and other hosts of things.

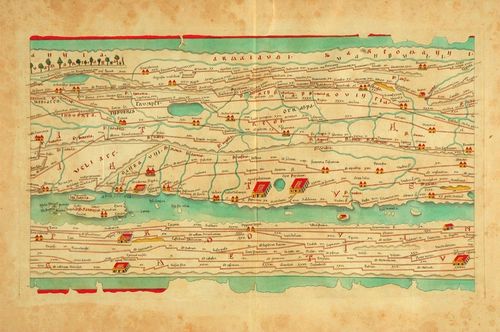

As much as detail is attractive to me—complex, staggering information correctly displayed—there is also the opposite: the quick, thoughtful, spare map. The Tabula Peutingeriana is sort of like that—this is a 17th century reproduction of an ancient Roman map that was, basically, a road map of the world (or the Roman World) that was linear and included all manner of detail of the roads themselves, with little else. It is a spectacular thing—one version I had once was 14 inches high and 16 feet long, just a skinny map of how to get around in the world from 2000 years ago. There was of course nothing “quick” about how the map was made, coming at the expense of countless hours of careful observation, keen observation, and lots of general human tragedy.

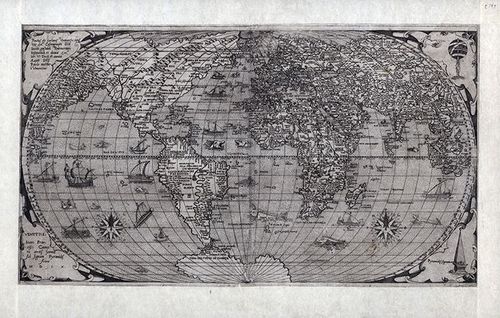

Folrani's world map of (ca.) 1575 (which appeared in Antoine Lafrery’s (1512–1577) Geografia tavole moderne di geographia) is a glorious thing and a fantastic accomplishment for its time (and also being the first map to use the name "Canada"). It has a sumptuous artistry to it in addition to including (and excluding) certain of the newly known discoveries. In this version of the map he chose to not use the newly-incorporated Straits of Ainan

[I'm sorry to say that I've misplaced the original source for this map--I will try and supply. My apologies.]

In another edition of the m-which appeared a few years later--North America is still attached to Asia, but now there is added another bit, a gigantic land mass to the south, Terra Incognita. This was basically put together by some sightings in the southern seas that located different land masses, and Forlani took it upon himself to connect all of those pieces of information and draw them into one continuous land mass, greatly expanding his own version of Antarctica from a few years earlier. It is a wonderful example of leaving something(big) out and making something else (even bigger) up.

But the map that I think I love the most illustrates Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, an Agony in Eight Fits, and occurs in the Bellman’s tale, starting the second fit. It begins:

The Bellman himself they all praised to the skies-

Such a carriage, such ease and such grace!

Such solemnity too! One could see he was wise,

The moment one look in his face!

He had bought a large map representing the sea,

Without the least vestige of land:

And the crew were much pleased when the found it to be

A map they could all understand.

"What's the good of Mercator's North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?"

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply,

"They are merely conventional signs!

"Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we've got our brave Captain to thank"

(So the crew would protest) "that he's bought us the best-

A perfect and absolute blank!"

Sometimes there is nothing so fine as something that beautifully illustrates the nothing that isn’t there, and this lovely map, unencumbered of all of the elements and details that define the mapness of something, perfectly explains the origin of its need.

For a lovely work on the complexities and simplicities and just sheer beauty of what things like maps are check out former Ashevillean Peter Turchi's Maps of the Imagination, the Writer as Cartographer.

Comments