JF Ptak Science Books Post 1628 History of Lines Series

In the long history of lines seldom do we see such an indirect way to get safely from point A to point B than by zig-zagging through points A1 to A201. But this was definitely the case for ships in the North Atlantic in the 1914-1918 period.

In the long history of lines seldom do we see such an indirect way to get safely from point A to point B than by zig-zagging through points A1 to A201. But this was definitely the case for ships in the North Atlantic in the 1914-1918 period.

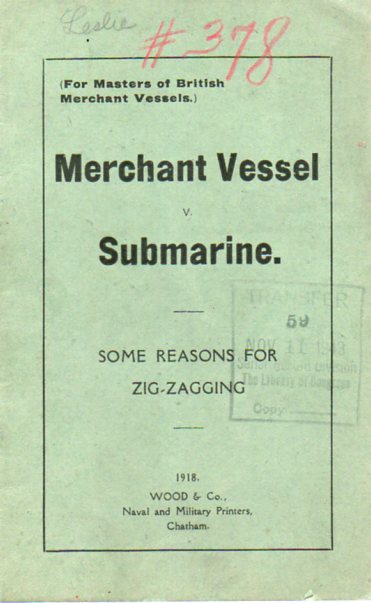

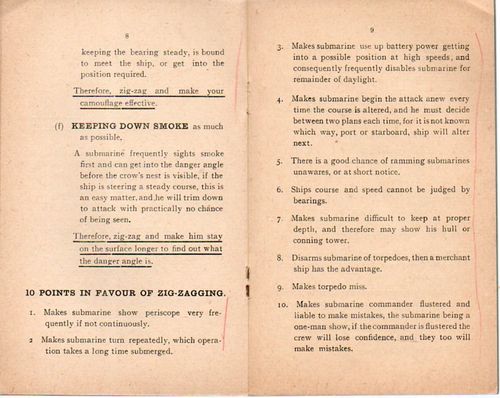

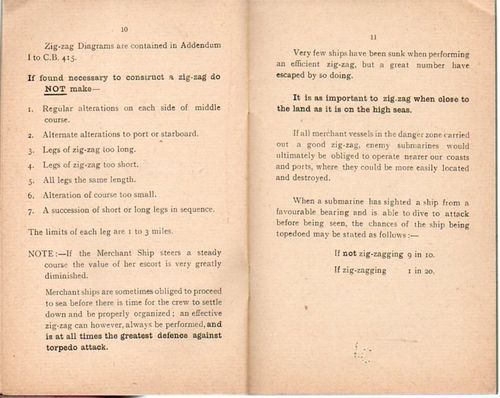

Merhcant Vessel v. Submarine, Some Reasons for Zig-Zagging (a "Confidential" report written by Lt. Commander A.G. Leslie and published by Wood & Co. in Chatham in 1918) presents logical, simple, workable solutions to the problem of the submarine, fallible solutions to what must have seemed to be infallible treachery. It is a pocket-sized, 5x3 inch talisman and survival guide for those ("For Masters of British Merchant Vessels") responsible for hundreds of lives and thousands of tons of ship, all of the good information boiled down to eight pages of loose type, a way to get around the subs, and weighing in at about an ounce.

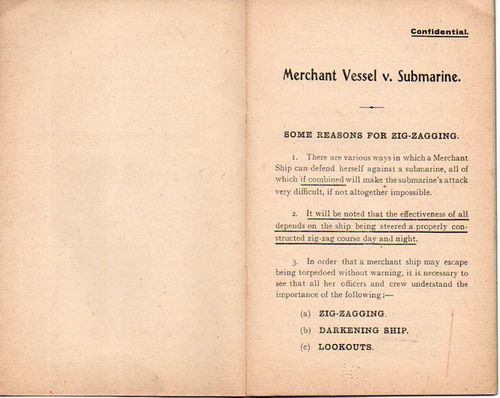

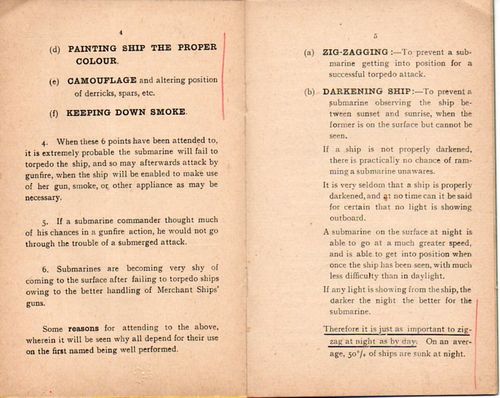

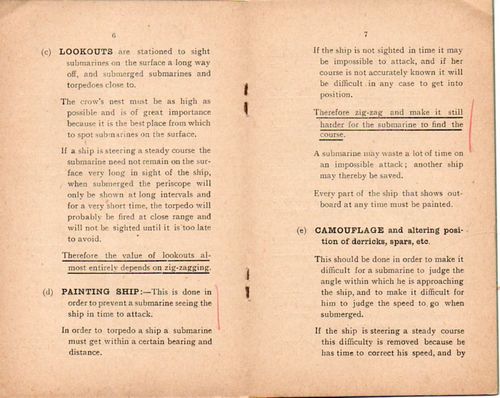

What it really boiled sown to was zig-zagging--plus darkening the ship, posting lookouts, painting the ship the proper color, camouflaging it, and keeping the lights and smoke down. But over th eight pages Leslie knocks down the idea of zig-zagging over and over again. And he was right of course, right on all of it, given the conditions of conflict and the state of development of the submarine and the torpedo. At this point, the torpedo was a point-and-shoot affair, which means the sub commander needed to get accurate info on the speed and the course of the ship (and other stuff of course)--and the one thing that would make this very difficult for the sub was for the ship to change its course unpredictably. That would mean longer follow time for the sub, longer time above the water line, probable multiple dives using up battery power, and so on, all very problematic for submariners.

Once unrestricted warfare was declared on 1 February 1917 the German subs attacked any and all shipping, including American ships, which led the way for American involvement in April. The U-boot sunk substantial part of British shipping, but, ultimately, it could not do enough against the escorted convey, and the German moment would be lost. In the end of it all, of the 360 submarines built by Germany, 178 were lost, after having waged a campaign for four years which saw the sinking of more than 11 million tons of shipping.

A straight line coursed by the ship would allow the sub to gather its information, site the ship, and sink it.

[The full text is below. I can't find another copy of this work in any of the likely places, including OCLC.]

Comments