JF Ptak Science Books Post 1621 Blank, Empty and Missing Things series

The thread on blank, empty and missing things becomes more interesting to me when it approaches the subject of humans and art. And perspective. It is a curious thing how over the course of 400 years--beginning say with the adoption of perspective in the work of Paolo Uccello--that the human form (and clothing and surroundings) was more and more realistically portrayed until it was not so, the "undoing" of perspective and realism coming with the Romantics and Impressionists, until realism and the portrayal of the very essence of a recognizable "thing" disappeared as a requirement in art in 1911.

But there are interesting forebears to the disappearing human, and some of them are found in the Renaissance. Of course they're mostly instructional on how to construct objects in proper perspective and such, but sometimes, well, sometimes they're not, and the artist is purely suggesting human form.

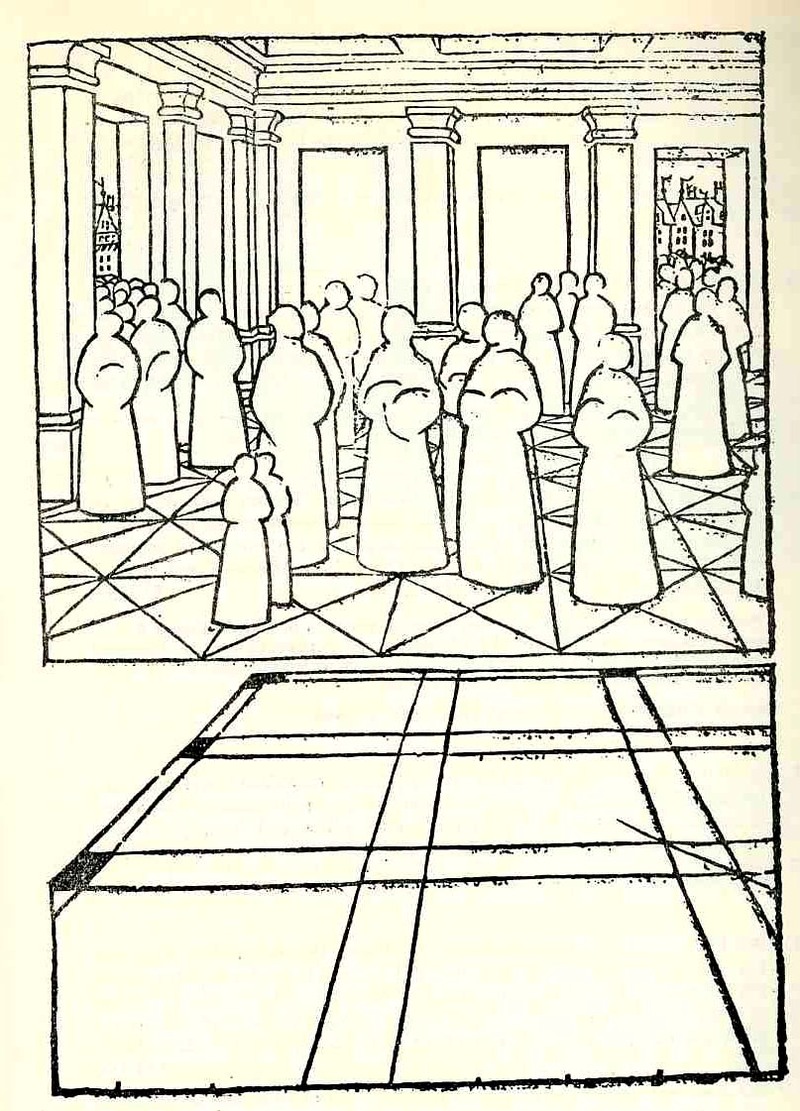

Take for example the extraordinary work of Jean Pelerin (also called "Viator”) in his De artificiali perpectiva, a very rare woodcut-illustrated book printed n Nurenberg in 1509. In illustrating what he referred to as his “three point perspective” Pelerin removed much of the gothic-tradition bric-a-brac that is so heavily favored in these early books and replaced them with outlines from his rather astonishingly expressive notebooks, and replacing people, individual humans, with what may be the first “almost-entirely-absent” human forms. These roundish, ghost-like figures are just meant to hold the outlines of space, meant to function in the role of a simple comparative unit. This works quite well as an artistic technique—a solicitation tool which I think gives his reduced, “empty” humans an incredible, ethereal look unlike any other in the history of the first 60 or so years of printing. It is difficult to imagine what the observer of these images back there in 1509 was thinking when they looked at these figures, and perhaps removed them from their textural context—it would have been a unique visual experience for them

Albrecht Durer's (1471-1528) drawing of a geometrical man was an amazing--startling, even--object to the early 16th century consciousness. His …Symmetria partium…humanorum corporum (1537) was a masterpiece, and a key piece of revolutionary visionary thinking.

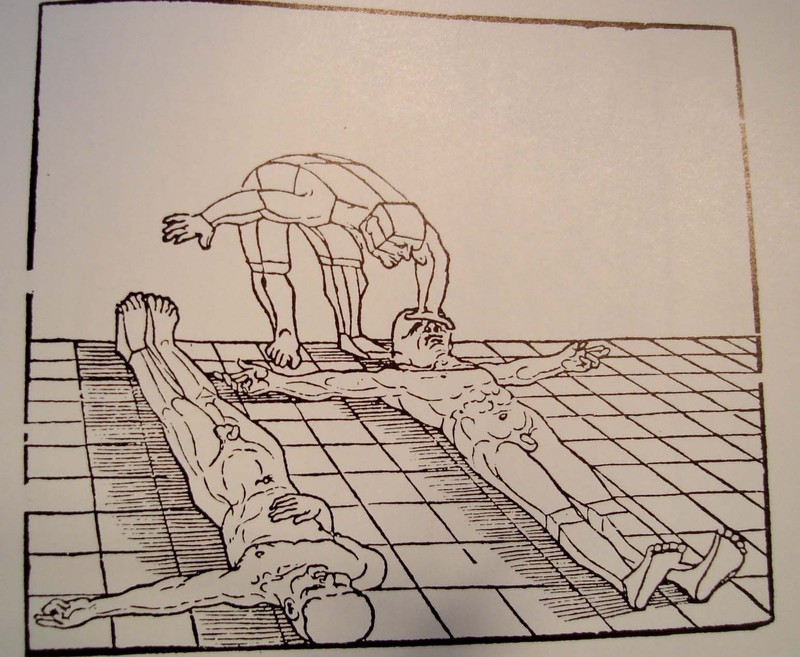

His Underwysung der Messung ("Treatise on Measuring") written about 500 years ago (in 1525) set the stage for this next work--it is here that we find some of the most recognizable of Durer's illustrations of the instruments that he employed to do his perspective work. Durer--so far as I can tell--created an orthographically rotating human figures in three-dimensional trapezoids, creating incredibly human-like non-human forms. Supra-human, perhaps; mechanized, calculated, structural. His use of stereometry, the science of measuring volume, was adapted to this study of human form and the relationship between that and movement.

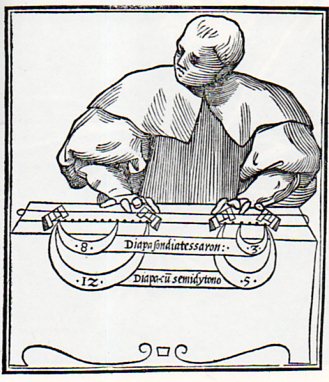

Lodovico Fogliani, Musica Theoretica (Venice, 1529) which is somewhat reminiscent of a more -blank figure, though when you look at the images in teh book, most of the human figures are more detailed and refined. This one seems only abotu half-done, with only the suggestion of a face and but little refinement in the clothing. The subject's fingers are also pre-robotic, like those fingers on a wooden manikin model if one had existed then. Of course the figure is just there to depict scales and that's about it, with just enough of a figure to stand as background to the transmitted info.

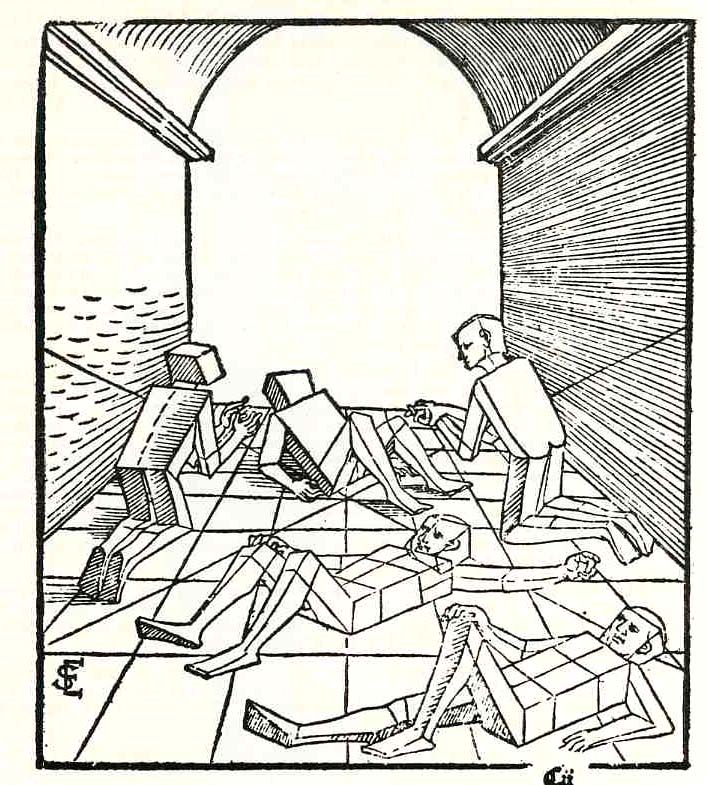

Just a little while latter Erhard Schoen, in his Unnderweissung der proportzion und stellung der posssen liegent und dtehent, printed in Nurenberg in 1538, presented another unique way of representing the human form in studying perspective. He used simplified geometric form to stand in for the curvy humans, replacing them with proportional stacks of boxes which would more easily explain to the younger reader how to represent the human body n space and in proportion to other things.

While at about the same time Luca Cambiaso (d. 1585) produced this woodcut, "The Rape of the Sabines", which is mostly light with bare shadow, depicting motion and emotion more than detail. This again is hundreds of years before its more modern 19th & 20th century descendants.

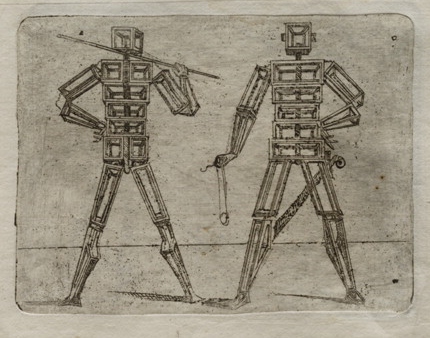

And also this figure, again by Cambiaso, and recalling the efforts of Durer and Schoen:

Coming outside the confines of the Renaissance but just too fantastic to not include (although I could just simply change the title of this post to accommodate all) is Giovanni Battista Braccelli's fabu-landscapes of the human condition, published in his Bizzarie di Varie Figure in 1624.

(My thanks again to Bibliodyssey for surfacing Braccelli for me, and also to The Rare Book Room for posting all of the images in that rare work, and of course to the Library of Congress/Lessing J. Rosenwald pages, who made the images available for downloading, here.)

And a little later after this last--and again well outside of the Renaissance--the idea of the missing man, an image I just couldn't resist:

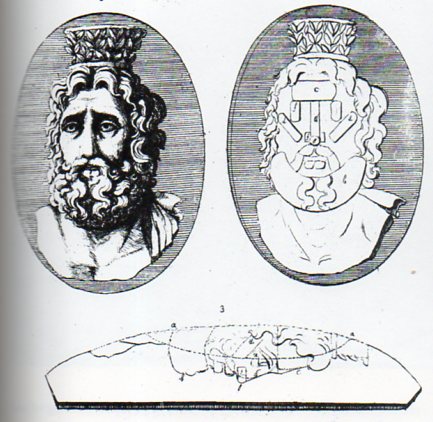

which is from the instructional by Laurent Natter, Traite de la methode antique (1754). The engraving is one of a series that shows the technical process of a antique method of constructing antique cameos and coins, and in this case how the gem would be produced by modern methods.

While I'm often dazzled to the point of muteness, squire, by your idiosyncratic approach to myriad esoteric subjects, I'm particularly fond of this entry for which many thanks.

I've been absorbed with that 2nd Cambiaso for YEARS (and if I might add 2 other important players - to my mind - in your theme(s): Heinrich Lautensack -> http://bibliodyssey.blogspot.com/2008/05/perspectiva.html and Giovanni Bracelli [linked in same post])

My obsession with Cambiaso derives from knowing that there are said to be several hundred sketches of his in existence owned by the Palazzo Rosso in Genoa and I keep fruitlessly searching to see if they've digitised any of them, every 8 months or so.

So thank you, sincerely. I love how perspective dances its empty and erratic way to cubism and surrealism.

Posted by: Peacay . | 02 October 2011 at 09:19 AM

THanks so much for that, PK! I read your excellent post (linked above) and will update mine later today. Cambiaso (from what I can tell) was a very interesting guy working across a number of different fields--I can understand your obsession!

Posted by: John F. Ptak | 02 October 2011 at 10:59 AM