JF Ptak Science Books Post 1617

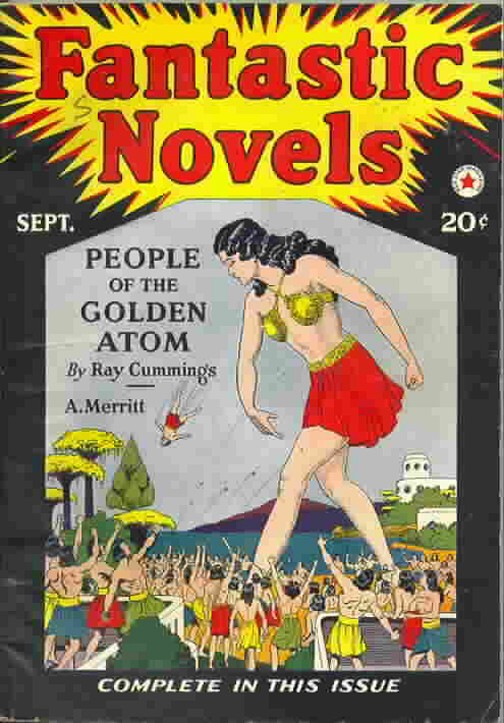

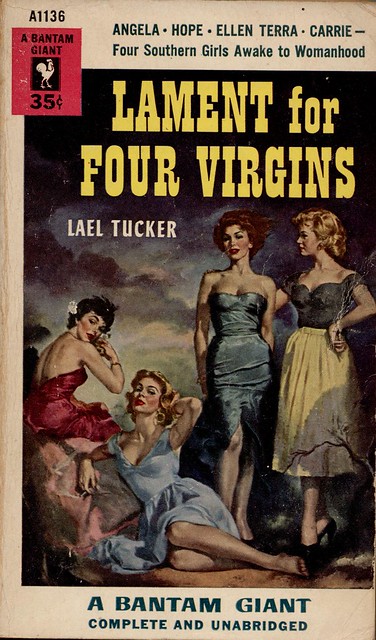

Sometimes things are just not what they seem to be. Sometimes they are deceptive and uncommon and somewhat hidden--and sometimes deceptive even to themselves. Sometimes the deception is intentional, and sometimes it is just a mistake, but a deceptive one. In the following cases, the deceptive elements are relating to size--kike the example below, in the cover illustration for the campy ("Southern" with names like those?) troubles of mid-1950's "girls awakening into womanhood":

If you take a closer look at the reclining figure just abpve the word "giant", you can see that she is one, unintentionally. She's just badly drawn, or something, a victim of foreshortening--we can see that her leg from her knee to her foot is as long as an entire keg of her companions, making this person about eight feet tall.

On the heels of the eight-foot-tall woman comes one who is far more famous, ultra-famous, really.

Le Dejeuner was a scandal when it was exhibited in 1863—Manet painted what he wanted to, unbound by perspective, by color, by composition, and on and on. The folks in the painting were not connected to anything, really, and were unconnected to each other, no one paying any of the others any mind, even when the women were naked. Nothing seems to be going on—the people are just simply there.

This is in itself was a disconnect from previous practices, the vision in painting was about something, and was directed. Light seems to be coming from a number of different places, and the shadows from the trees reflect this, simultaneously stretched towards and away from the light sources. The bathing woman in the background, or what used to be background, had she been drawn using proper perspective, would’ve been about nine feet tall. But what happens here is that there is no foreground or background in this painting, just middle. It was this collection of abandonments, starting here in the Le Dejeuner in 1863, that ushered in the modern in art.

Then there's the fifty-foot-tall woman who really isn't that tall in relation to the people around here.

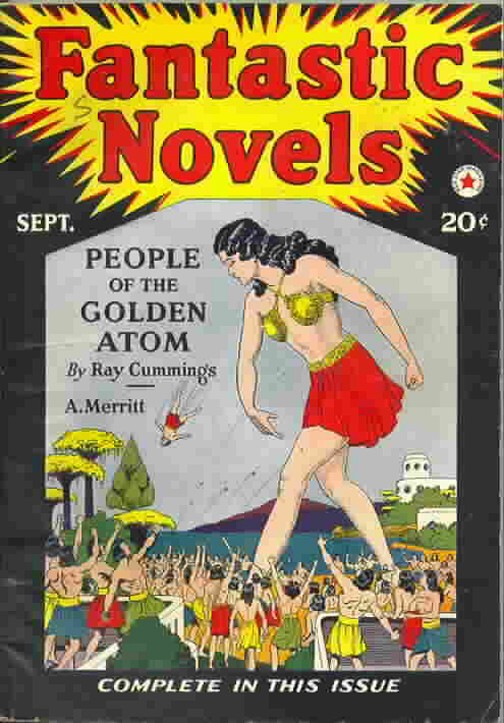

There are times when even things that are made to look extraordinary and plainly, outrageously identifiable as what they are, simply aren't--and sometimes they're not even close. For example, this cover of

Fantastic Novels (1921?) seems to tell a straightforward story, but as it turns out the giant

is giant but one living within a world in an atom of a gold wedding ring. (I told a fuller version of the story of thiis

here.) So this giant is a giant but only so in her own world.

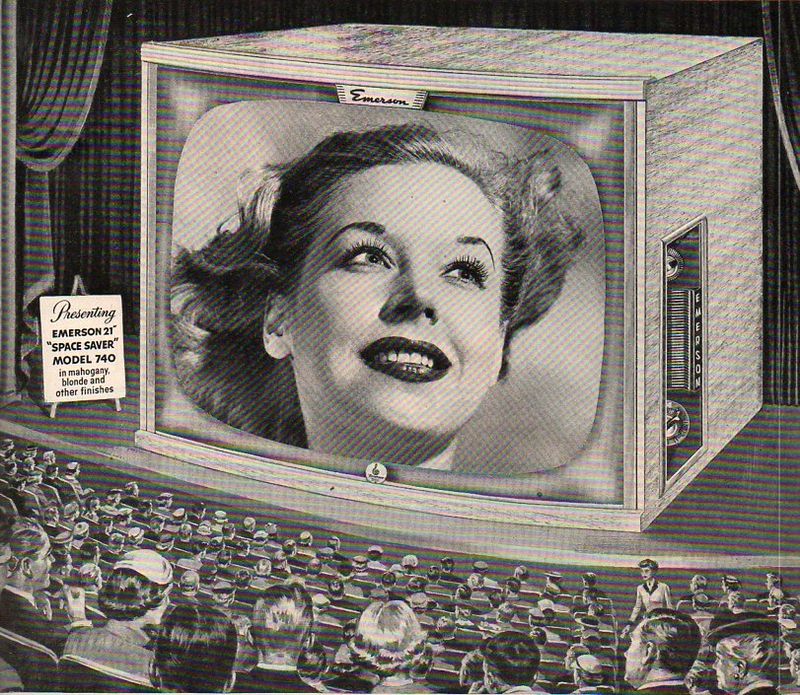

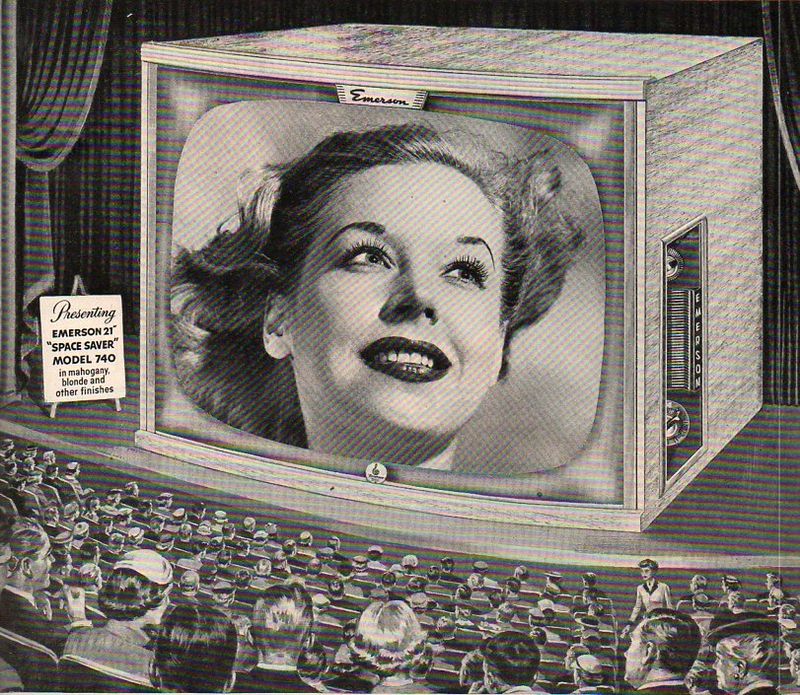

Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, Hobbes’ Leviathan, the Buddha at Yungang (Shanxi) and Melville’s whale were all pushed to their competitive monsterous edges in the 1950's, when you were more likely to think of The Bomb and creeping Communism before thinking back to any of these great representations. And it is also my general impression, having been paging through Life magazine for the 1950's, that there are some other major, lesser heralds of gigantism, especially if you paid attention only to the advertisements. There were 1950's colossal characters who were pale imitators of their earlier counterparts–the Amazing Colossal Man and Colossal Woman being two minor mirrors of older ideas--but they hardly contained the colossal ideas that were resident in the earlier creations. (Perhaps part of that is due to having just witnessed the demise of two enoromities in Hitler Stalin.) But this woman seems to be the largest of the lot--I make her to be about 100 feet tall. There's really nothing deceptive about her, except of course that this giant is only a head.

Comments