JF Ptak Science Books Post 1606

Today (September 9) in 1 797 was the day of the death of Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin), an English feminist and anarchist, best known for her tract Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and also for being the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Shelley), the author of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. In all likelihood, Ms. Godwin died after complications in the birth of her daughter, giving way to "childhood fever".

797 was the day of the death of Mary Wollstonecraft (Godwin), an English feminist and anarchist, best known for her tract Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and also for being the mother of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Shelley), the author of Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. In all likelihood, Ms. Godwin died after complications in the birth of her daughter, giving way to "childhood fever".

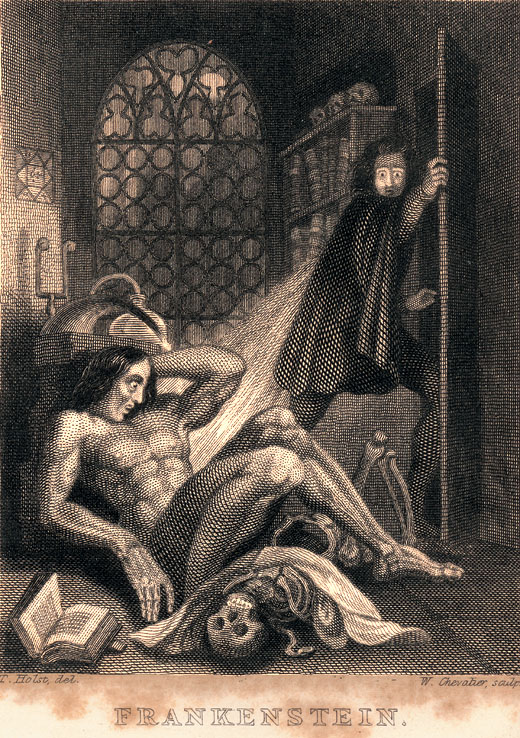

The first time that Mary Shelley's name appears on her Frankenstein... is on the title page of the second edition of the work, when it was printed in France in 1831, thirteen years after the anonymous Parisian printing of the first edition. My guess is that a woman's name--despite her high literary lineage--would just not fit on the title page of such an untoward, beastly book in which the monster of Frankenstein was created., and which was decidedly ungodly, a possible blasphemy.

But when the second edition was published, in addition to the other changes that she made to the book--substantial, meaningful changes that suggest to scholars that the real, or intentional, Frankenstein produced by Shelley remains in the first edition--there was included a very interesting introduction. It is in this intro that Shelley shares her story of the creation of this unusual book, as well as the literary and scientific influences in creating it--a sort of intellectual heritage to the idea, an outline of the process of her creativity that led to Frankenstein.

The book is better known for the numerous movies that were very loosely based on it, and truth be told the book has a far greater depth to it than any of the movies ever remotely hoped to achieve--they were after unsettling horror, whereas the book was concerned with that plus the interplay of Romanticism and science/technology, and the understanding of the way in which life begins and how the brain acquires information. I think that was she was looking for was the essence of things out there somewhere in the empire1 of man.

Shelley was influenced by a number of different scientists (though the term itself, "scientist", wouldn't be used for the first time until decades after the book was published) , some of whom wrote on the subject of Vitalism and other Romatic-era sensibilities rubbing up against the new technical revolution and objectivist capacities, and the supposed capacity of electricity via Galvanism (and the work of Mesmer and Galvani) to restore life to the dead. As Shelley writes in the introduction of the second edition: "Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth". She wrote with accomplishment, a very nice prose, weaving a tale of Newtonian-Woodsworthian-Galvanism-Volatarianism, a Romantic-Scientist.

But the Darwin that Shelley refers to in 1831 is of course Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles, and someone who I think Shelley didn't actually read, but had heard about. So I think that the influence of Darwin on Shelley came through bits of remembered pieces from Percy and Byron, and only suggestive of what Darwin was writing about. (Even the reference to Darwin in the 1831 introduction is not there--she refers to what Darwin was writing about in the section 'Spontaneous Vitality of Microscopic Animals' in the notes section of his The Temple of Nature, and doesn't really quite get that part right, though if what Darwin was writing about could be described as a chocolate milk shake, Shelley could indeed say that the drink was chocolatey.

The book is really quite an achievement, especially given its time; and the intro to the second edition is an unexpected revelation into how someone comes up with an idea. A big idea.

The other influence in he writing of Frankenstein...--much of the book was conceived while Shelley was pregnant, a pregnancy which ended in a miscarriage and which almost cost Shelley her life. (Shelley gave birth to four children, only one of whom lived into maturity.) The book also came a few years after two suicides in her family. Life. Regeneration. Birth. Creation.

Notes:

Francis Bacon would tell us that

But if a man endeavor to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe, his ambition (if ambition it can be called) is without doubt both a more wholesome and a more noble thing than the other two. Now the empire of man over things depends wholly on the arts and sciences. For we cannot command nature except by obeying her. Francis Bacon, 1620 Aphorism 129,' Novum Organum ("The New Organon, or True Directions COncerning the Interpretation of Nature), Book I (1620

Comments