JF Ptak Science Books Post 1568

John Wilkins' construction of a new, theoretical language, a visual semantics of idea that was to be read and not spoken, a new international language to communicate thought, seems straight from the heart of the great Jorge Luis Borges. And in fact, Wilkins does come from Borges, in a way--as part of a story Borges wrote in 1942, a fantastical semi-non-fictional account of Wilkins' fabulous effort1.

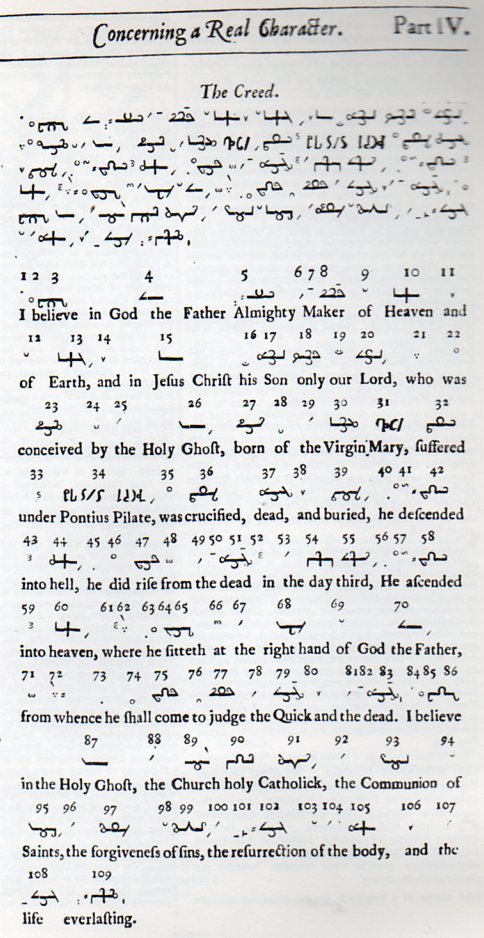

Wilkins was a 17th century figure with a sort-of 20th century idea, but even advanced to this point in time, and with actual mathematical and linguistic tools at his disposal, his work is still better as a sci-fi movie backdrop than anything else--not that there's anything wrong with that. The book of his in question, An Essay towards a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language, was published in London in 1668, and was an very interesting, Aristotelian non-standard approach to construct a universally understood language composed of characters which were in a way axiomatic of a developing system of genera, a taxonomy of ideas, that were somehow, fantastically, capable of expressing the foundations and flights of human thinking.

Borges' presented Wilkins in a very Borgesian way in his "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins", mixing fact with creative fancy, exhibiting Real Character as though it was being re-discovered and studied by living academics.

It reminds me somewhat of other massive buit not-quite-nowhere-near-there efforts by people like Oliver Byrne and his color-coded approach to Euclid (1847), J.H. Woodger with his Axomatic Methods in Biology (1937), and Clark Hull's Principles of Behavior (1944). Fascinating ideas, constructed with big brains, but which ultimately produce a product which more deeply confuses and obscures the subject matter it set out to explain--and which don't really work, anyway. But they are beautiful things int heir own right--Byrne's work in particular also happened to be one of the most beautiful books produced in the 19th century--assemblies of bits and pieces that are occasionally magnificent but whose final destination was of course The Twilight Zone.

They were in some way a Search for a Perfect Language (as in the work by Umberto Eco); they sought to step deeply outside themselves in an effort to grasp a higher knowledge, perhaps not much too unlike Isaac Newton and his deep experimentation in alchemy, looking for the massive truths that were handed down to the few selected ancient ones. They are beautiful things with a lot of very good thinking--they just weren't right.

Notes:

1. "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins", 1942, in which Borges presents an imaginary intellectual archaeologist assessing the work, comparing it in particular to the imaginary encyclopedia Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge.

"He divided the universe into forty categories or genera, these being further subdivided into differences, which were subdivided into species. He assigned to each genus a monosyllable of two letters; to each difference, a consonant; to each species, a vowel. For example: de, which means an element; deb, the first of the elements, fire; deba, a part of the element fire, a flame. In a similar language invented by Letellier (1850) a means animal; ab, mammal; abo, carnivore; aboj, feline; aboje, cat; abi, herbivore; abiv, horse; etc. In the language of Bonifacio Sotos Ochando (1845) imaba means building; imaca, harem; imafe, hospital; imafo, pesthouse; imari, house; imaru, country house; imedo, post; imede, pillar; imego, floor; imela, ceiling; imogo, window; bire, bookbinder; birer, bookbinding. (This last list belongs to a book printed in Buenos Aires in 1886, the Curso de Lengua Universal, by Dr. Pedro Mata.)"--Jorge Luis Borges

Borges described Wilkins' taxonomy as follows, dividing it into 14 categories (compared to the original Wilkins list of 40):

Those that belong to the emperor; Embalmed ones; Those that are trained; Suckling pigs; Mermaids; Fabulous ones; Stray dogs; Those that are included in this classification; Those that tremble as if they were mad; Innumerable ones; Those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush; Et cetera; Those that have just broken the flower vase; Those that, at a distance, resemble flies.

Comments