JF Ptak Science Books Post 1591 -

-

- “Hence after Plato has, by succession from Pythagorean doctrine and by the divine profundity of his own genius, shown that apart from these ratios (i.e. musical ratios) there can be no possibility of conjunction: in his Timaeus, he constitutes the soul of the world by means of the com- position of those ratios, by the ineffable providence of God the craftsman. Consequently the soul of the world, which propels into movement this body of the universe visible to us, being constructed of ratios which created from themselves a musical concord, must of necessity produce musical sounds from the movement which it provides by its proper impulse having found the origin of them in the craftsmanship of its own composition.” --Isaac Newton on Plato and the rest of the cast of classical and ancient authorities, summarizing the common thread on music and the construction of the universe—that being the correlations of the orderliness of music and the heavens.

Newton did not intend notes like these to be published during his lifetime—as was the case with more than one million words that he dedicated to his very close and scientific research in the fields of alchemy and alchemical chemistry. It is interesting to think of what sort of censorship went on with this work and long, deep interest of Newton’s—fully one-third of all of the scientific books that were in his library were dedicated to alchemy, and great gobs of his time was spent in alchemical pursuit, but most of this did not come to light until John Maynard Keynes purchase most of the this manuscript material at auction (!!) in 1936.

Newton was trying to find something that he thought only he might be able to see, trying to press his ear closer to god’s lips in whatever way possible—but for other scientists and non-modern historians of science, these pursuits seemed cumbersome, an embarrassment.

I bring all of this up to get at what must’ve looked like a very anti-mechanical, discordant, and very non-rational set of images used to quickly convey a philosophy.

The great illustrator and social watchdog Thomas Nast discovered the power of the image in the 1860’s and 1870’s, when he was able to convey a message to readers and illiterates alike by creating very graphic displays of public corruptions and (some) social imbalances. Of course this approach has been used for thousands of years, and is time-honored, but the spread of ideas via image in published media is not terrifically old. (And by this media I mean by books or broadside, and not by paintings, which were generally intended for an incredibly small audience in the pre-museum days. Messages were certainly displayed in this way for thousands of years, and most of these were messages of fear and loathing of unacceptable behaviors. The Renaissance is beautiful but left little doubt about who was in control and what was deemed appropriate ways of acting and thinking—the church was the major patron of the arts, and its not for nothing that we see mostly passionate genuflectorial praise for the supreme being and his associates.)

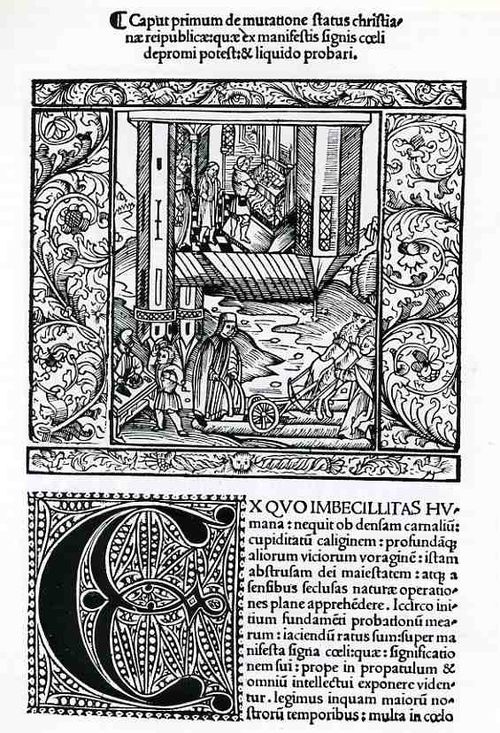

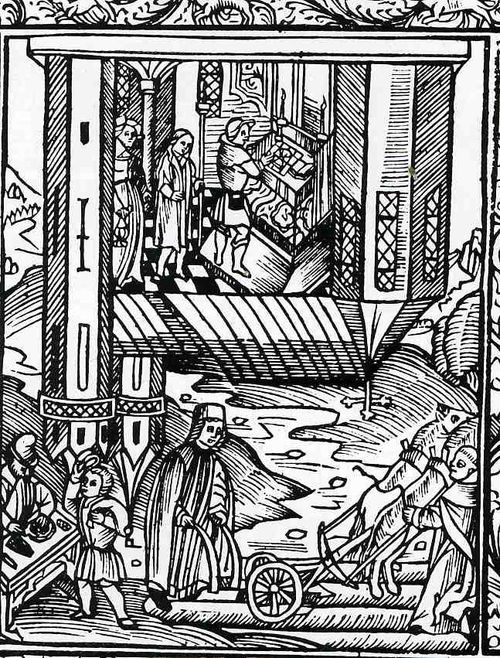

And this brings us, I guess, to where I was trying to get all along—the superb images found in Joseph Gruenpeck’s (1473-1532) Speculum Naturalis Coelestis & Visionis…, a small folio published in Nurnberg in 1508 and illustrated with 13 fantastic woodcuts by the artist Wolf Traut (1486-1520). Gruenpeck, who gave up his office as astrologer to Emperor Maximillian II to become a priest and to undertake the writing of this book, produced a pre-Reformation masterpiece, whose very sharp criticism of the church helped fuel the revolutionary fires among the peasants which eventually led to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1523-1525. What is remarkable to me about the illustrations in this book are their head-butting discordant nature—one sees instantly that something is defiantly skewed, demanding the viewer’s attention—from there a very quick and generally acerbic message is delivered with great ease. These were messages that were instantly understandable and translatable across language and culture, and it is perhaps for these reasons that this work was so important in helping to form a new social consciousness—much in the same way as more popular mass-communicators like Thomas Nast would do hundreds of years hence.

Now, the Traut woodcut: this is one of those very uncommon occurrences when a familiar object is place in it “opposite”, out-of-place position to attract the viewer’s attention—in this case, it is an upside-down church. Not only is the allegorical church placed on its head, we see too that its clerics are outside tilling the soil, while the peasants and field workers are inside the church celebrating Mass, their positions in society switched It is unlikely that such a book would’ve been in the hands of someone who couldn’t read, but, nonetheless, the image is still very powerful and must’ve made a big impact on any observer, it being such a strong attack on the foundation of the church.

Recognition comes in many forms and flavors, as in the superb mechanical universe of Sir Isaac or the beautiful and melodious music of the spheres of Johannes Kepler; it sometimes comes via opposites and discordant methods, with the logic of Kurt Goedel, or with the images of Wolf Traut--either end pulls equally at opposite tails of the labyrinth, and a much-improved choice over a lottery in Babel.

Comments