JF Ptak Science Books Post 1569

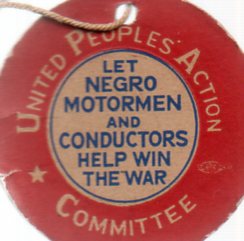

This political "button" has been in my house --along with a a dozen or two others--for quite some time, small signifiers for large events. This one, though, is more suggestive than assertive; a measured, tenuous political statement that seems today as though there should have been no disagreement in its message.

The button was issued in 1944, at what might have been the very most crucial time for America in fighting World War II. The message wasn't to support the idea of sending Black Americans to fight in the war--it was rather a call to White America to acknowledge the need for employing Black Americans as motormen and conductors on Philadelphia street cars as replacements of the men who went off to fight the war.

There was very strong resistance to having Black people interact with White people on a public convenience.

In the same year, in July 1944, Jackie Robinson (then of UCLA) was a newly-commissioned 2nd lieutenant in the United States Army, stationed in Fort Hood, Texas, with the legendary 761st "Black Panthers" Tank Battalion. On 6 July he boarded a U.S. Army desegregated bus, where he was told by the driver to move to the back, into the Negro section; Robinson refused; the driver backed down, and continued on his way, though not without his revenge. At the end of the run, he alerted Military Police, who would arrest Robinson on a variety of phoney charges. It was recommended that Robinson be court-martialed. The commander of the 761st, a White colonel named Paul Bates, refused to do so--which led Robinson to be transferred to the 758th Battalion where there was no problem in undertaking the legal action. By August, with charges reduced, Robinson went to court and his charges were dismissed. But by that time, the damage was done, and he would not be sent overseas to fight. He was sent to Camp Breckinridge in Kentucky where he served as an athletics coach for the few months he had in the Army, and he was honorably discharged in November, 1944. It was while he was at Breckinridge that a former Negro Leagues player for the Kansas City Monarchs suggested that Robinson write to the ballclub for a tryout. He did, they did, and the rest is history.

In 1944 in Philadelphia--though it could have been in many other cities in the northern part of the United States, though this would not have been attempted almost anywhere in the South outside of the Pullman car--the question was whether society would tolerate a Black person interacting with White customers on streetcars.

In 1944 in Philadelphia--though it could have been in many other cities in the northern part of the United States, though this would not have been attempted almost anywhere in the South outside of the Pullman car--the question was whether society would tolerate a Black person interacting with White customers on streetcars.

It was almost at this same time, in November 1944, that General Eisenhower decided to send Black troops to fight with Whites in battle. There was strong resistance to this behavior in the military, not the least of which came from Ike's own chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith. It would take an Executive Order (#9981) from the next president, Harry Truman, to end the de facto segregation of the U.S. Army; it would take another war, and another three years (to the day) for the U.S. Army to announce its plans to desegregate, on 26 July 1951.

In spite of there being motormen and conductors working in other northern cities like Cleveland, Detroit and Indianapolis, wrapping the string for the United People's Action Committee around a button on your shirt or jacket would have been a controversial step to take--a step that looks alarmingly small to us here in the future, but it was a societally big one back in 1944.

Comments