JF Ptak Science Books Post 1521

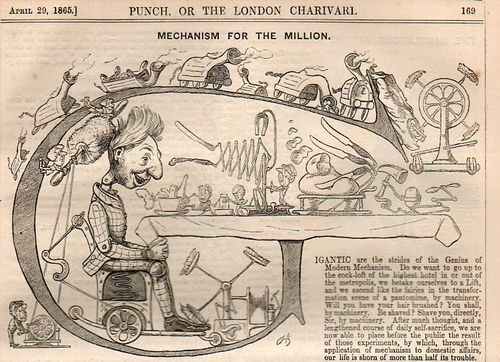

In the weeks following Lincoln's assassination (14 April 1865) the editors of Punch, or the London Charivari printed this arresting image of an imagined near-future:

And what the future holds is this: the automatic hydraulic teapot (already "sugared and milked"), automatic boot and clothes brushing, auto bread-cutting, carving, cork drawing, sweeping, letter writing, reading..."all done by machinery". "We shall cook by machinery; we shall have our mashed potatoes by machinery."

There is no specification about how all of this was going to happen--I'd be very interested about the automatic "letter writing and reading" would be, particularly when we read in the next paragraph, that "Mr. Babbage's Calculator is a mere mechanical infant to our gradually matured inventions". The article continues: "From thinking of machinery we shall at last arrive at thinking by machinery, and Man himself shall be, as presented in this initial etching, a mere machine."

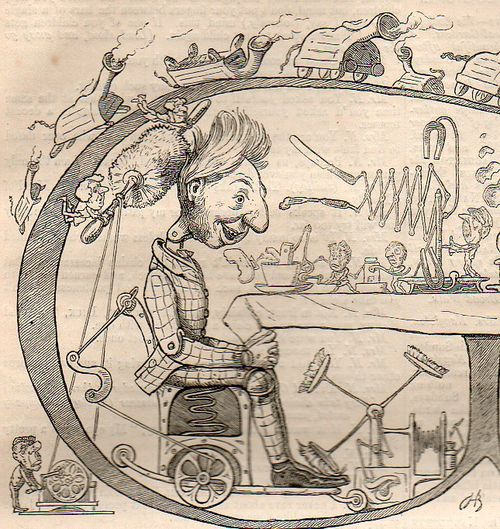

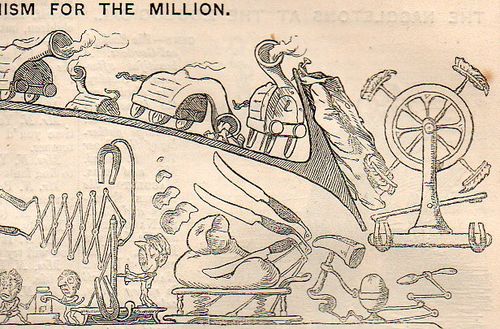

We see in the image that there are all manner of automatons pleasing the seated (mechanical) man, though they are all powered by steam, or friction, or by magnets, all existing power sources and almost everything being doable at that point in time.

And the detail:

There is a suggestion of a "Finding Fault Machine" but this goes barely beyond its mention--except to say that it would destroy something and become our next "Infernal Engine". I initially liked the sound of the title of this machine, though it quickly started to seem like a god machine to me--something that could and would have the ability to find faults in things, and then, I guess "correct" them in some sort of Steampunk God way. I'm not very educated in the world of speculative/science fiction to determine how early people began to imagine constructing their own supreme deity, though it seems to me that this must be considered an early effort. I do have large doubt that the Steampunk God is what these folks were talking about since it would most probably be a blasphemy, but there is certainly room to reach that conclusion.

The idea of a popular machine that was somehow associated with either Babbage's (1791-1871) difference engine or analytical engine (which was a programmable machine that would function with punch cards) and automated or mechanical reading and writing is very intriguing. It is unsure whether the editor was crediting the future with a machine that would provide the imagination behind writing, or provide an instrument that would record thoughts and creativity directly to some medium as they occurred, or what have you. It is an interesting idea left very open-ended to the reader, which remains so even to the modern eye, because what happens with statements like this is that they get back-filled with whatever current technology exists. In 1865, the other innovations depicted for the future were mainly driven by steam, and perhaps this automated writer/reader would be too, something very primitive by our standards today, perhaps some sort of small steam engine that would help dip a quill into an ink pot....or perhaps it was simply something as exotic as a pen with endless ink. But I think if you look hard enough at the statement it is possible to see something like an internet.

And there were 19th-century something-like-an-internet things being imagined, if you can imagine the internet as an entity not created by a computer network, since the "computer" as we know it would not exist for these inventive folks (below) for another 50 or 75 years.

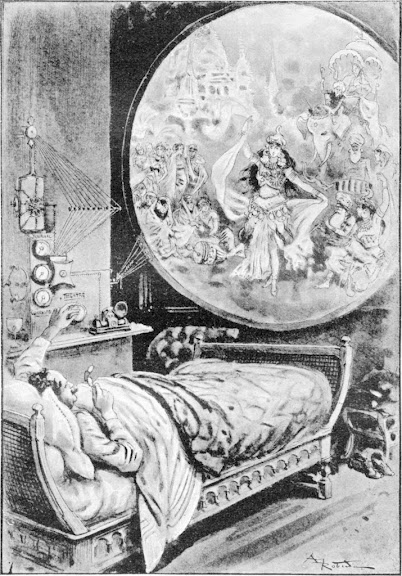

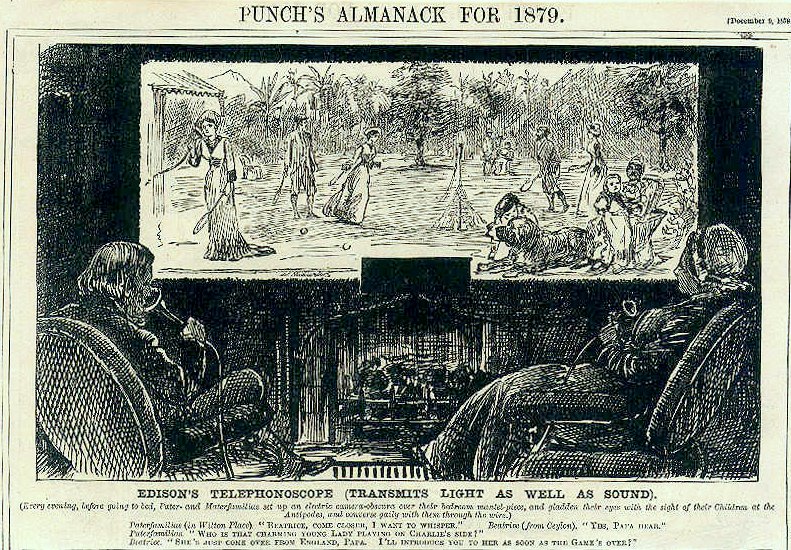

Edison's was there, of course, imaging a communication device that would show live-action events in which two remote parties could see and talk to one another. A version of his Telephonoscope: appeared in Punch's Almanack for 1879 and was aimed at the imagination and experience of only the classes of leisure and privilege:

There is also a device like this that appears in Albert Robida's Le Vingtieme Siecle: la Vie Electrique (1890) , which is an odd but very nicely illustrated look into the future of 1955--most of which has come to pass.

Another sort of live-action and direct communication device was depicted in Camille Flammarion's La Fin du Monde (1893):

Comments