JF Ptak Science Books Post 1400

Sometimes things that we take for granted—the “of course” kinds of things that were seemingly always here because they’re just, well, so obvious—that one needs to take a step back to appreciate their discovery, or invention, and to mind the fact that someone did have to actually bring these things to some sort of birth.

Sometimes things that we take for granted—the “of course” kinds of things that were seemingly always here because they’re just, well, so obvious—that one needs to take a step back to appreciate their discovery, or invention, and to mind the fact that someone did have to actually bring these things to some sort of birth.

These two (seeing and touching) would make great entries in our fictional encyclopedia--who was the first person to see ("ah, it was Nem Teff in 8211 BCE, in an area very close to the teeming slum of today's Bagdahd; he of course was a disciple of the Shenta-kra philosopher Boot Strap, who only four generations earlier came up with the idea of "touching". What people did to get around before Mr. Strap invented touching and before people could see is a matter for wide conjecture"--Pastor Steng "No Stink" Pallor, writing in the volume "I" of The Great Encyclopedia of Unknown, Non-Existent and Ficticious Things, published in New York City by Phantom Touch Press, 1972.)

But we're dealing with new applications of sight and touch here, although by and large these applications had a huge impact on the rest of civilization on their own merits.

Take for example the lovely Jean Nicolas Louis Durand. He was a radical rationalist, an advanced thinker in the field of architecture and one of the most influential instructors and writers on architectural history and theory of first half  of the nineteenth century. Durand also had his wild side, as well, but that took place when he was in his carefree (read: “adventurous”) thirties—this period of enormous and unusually creative work in architectural design also took place during the French Revolution, which was a bad time to be thinking this stuff up, let alone building it. (Some of the other French visionary architects of this time nearly lost their heads because of their non-revolutionary creativeness, but that’s another story.)

of the nineteenth century. Durand also had his wild side, as well, but that took place when he was in his carefree (read: “adventurous”) thirties—this period of enormous and unusually creative work in architectural design also took place during the French Revolution, which was a bad time to be thinking this stuff up, let alone building it. (Some of the other French visionary architects of this time nearly lost their heads because of their non-revolutionary creativeness, but that’s another story.)

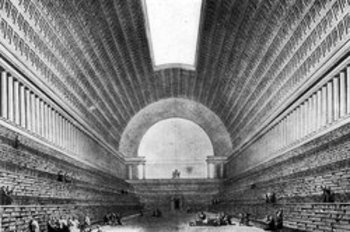

(This is Boullee's design of the megamonumental library for the king, 1784)

Durand came about this intuition naturally and also because he was a draftsman for the great Etienne Boullee, who we mentioned a few posts ago. (Durand would he execute a series of drawings entitled Rudimenta Operis Magni et Disciplinae, which are probably a pictorial representation of Boullée’s theories.)

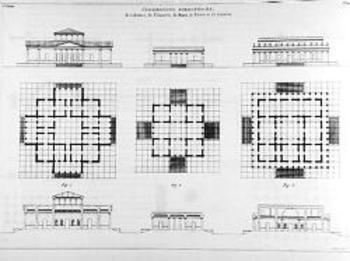

What Durand introduced however that was so revolutionary and so much his own was this—he was the very first architect to publish a work of comparative architecture in which all of the buildings were drawn on the same scale.

That means that previous works—all previous works—of comparative architecture compared one piece of architecture to another on different scales. That would seem to be a truly bad idea, given the nature of the comparative beast and all, but there you have it. I really have no explanation for why this was the case, or why it took until Durand’s Recueil et parallele des edifices en tout genre…(1832) to make it so in the fourth century of the publication of works on architecture, but it did.

Another example of what would seem to be sublimely obvious was the innovation of a Scottish surgeon in 1867 . People today I think intuit his surname from exposure to television commercials for a certain mouthwash, but this would be like knowing the importance of Isaac Newton from those figgy cookies—and that just isn’t right. Joseph Lister (1827-1912) figured out—through exposure to ideas by Ignaz Semmelweiss and Louis Pasteur, among others—that the infections in wounds that caused so many surgical deaths was not caused by the miasma in the air, but by something entirely different.

. People today I think intuit his surname from exposure to television commercials for a certain mouthwash, but this would be like knowing the importance of Isaac Newton from those figgy cookies—and that just isn’t right. Joseph Lister (1827-1912) figured out—through exposure to ideas by Ignaz Semmelweiss and Louis Pasteur, among others—that the infections in wounds that caused so many surgical deaths was not caused by the miasma in the air, but by something entirely different.

In his article in The Lancet of 21 September 1867 (and in his subsequent publication in book form later that year called Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery he explained what he thought was the cause—microorganisms that traveled (at least) from the surgeon’s hands onto the wound, and not by something floating around in the air. He began treating wounds with a solution of carbolic acid (which had been used  previously to remove the stinking stench from sewerage), and saw immediate results in the prevention of infection and gangrene. His next big step was to have surgeons wash their hands with the solution and wear gloves during surgery—because, up until then, surgeons went from dinner to intestines without the necessary benefit of having clean hands or wearing gloves. This seeming minor change in surgical procedure resulted, I think, in saving more lives than any other procedure ever invented. And it was mainly, really, from washing your hands before putting them into someone else’s body.

previously to remove the stinking stench from sewerage), and saw immediate results in the prevention of infection and gangrene. His next big step was to have surgeons wash their hands with the solution and wear gloves during surgery—because, up until then, surgeons went from dinner to intestines without the necessary benefit of having clean hands or wearing gloves. This seeming minor change in surgical procedure resulted, I think, in saving more lives than any other procedure ever invented. And it was mainly, really, from washing your hands before putting them into someone else’s body.

Comments