JF Ptak Science Books Post 1350

A.M. Worthington published his extraordinary researches in capturing drops and splashes just a year after the invention of the telephone--seeing his very quietly magnificent work would've been worth the phone call, even at those heady rates at the beginning of the new medium. Worthington was the first in his field, and for a short while, before he told anyone, he was the only person on the planet who had ever seen the fantastic complexity of this very common and previously-simple event. In its own way these photographs showing the deformation of a drop of milk (and mercury) were as much a revolution as the images shown by Robert Hooke in his epochal Micrographia in which he (just about the next-best-thing to Newton) introduced the fabulous complexities of the previously microscopical world(s).

Worthington and Hooke are two in a long line of people who brought unseen worlds into the visible sphere. Isaac Newton's (1642-1727) reflecting telescope (1672) gave a brighter vision to the observable universe; Galileo Galilei created an observable universe an order of magnitude larger than ahead ever been seen before in just one action, in one evening. Christoph Scheiner put a face on the sun in 1611, Henry Mosely gave geometrical growth patterns to the nautilus shell in 1838, James Fraunhoefer found out the chemical constituents of the sun in 1814, Watson/Crick (and Rosalind Franklin, really) emerged the helix of DNA in 1953, Wilhelm Roentgen presented pictures of the internal structure of living humans without a single drop of blood in 1895, and on and on, all providing us with spectacular images of what these people saw.

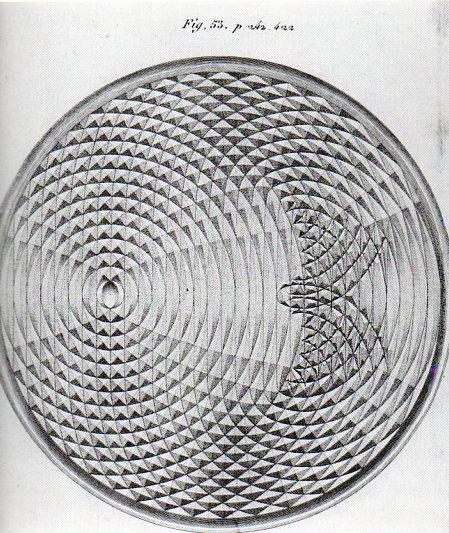

Chladni's images of the vibrations made from a bow on a violin string caught on sand-topped metal plates:

Worthington's visions into the small, oblique world of ephemeral occurrences gave these things a wider world to themselves; seeing their structure, their complexities, and getting the viewer into their tiny worlds made everyone who could think about such things a better person for doing so.

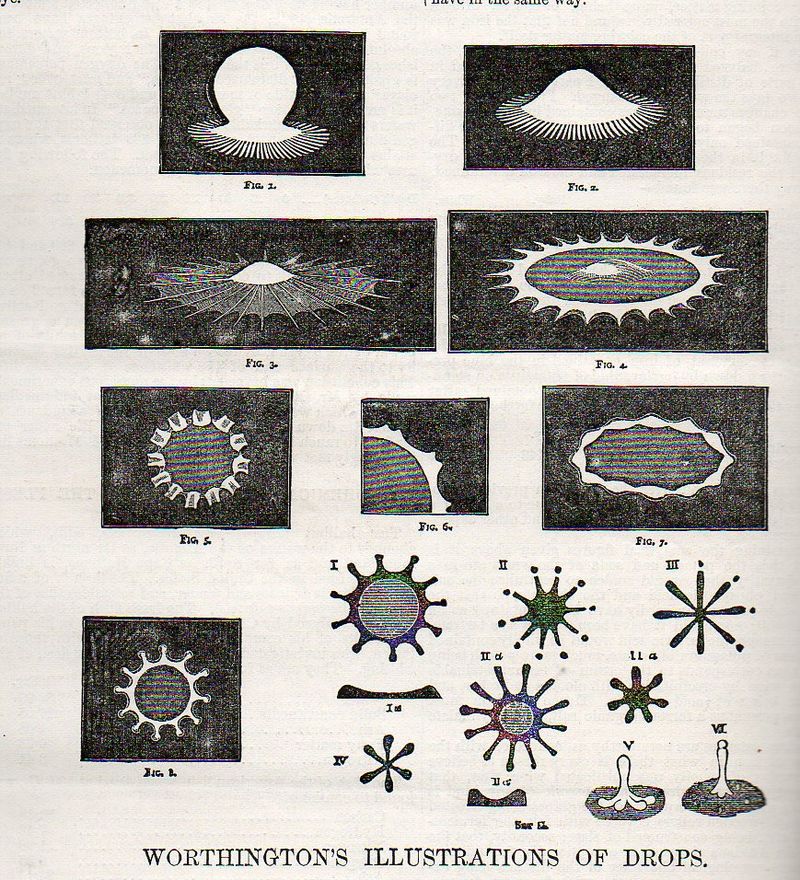

The series of semi-photographic images that Worthington was able to make of the drops and splashes could not be readily reproduced in his short article ("On Drops") published in the Scientific American (25 August 1877, and available for purchase at our blog bookstore) at this time--the half-tone was still a few years away, and the only way outside of making a drawing after the photograph in 1877 would've been a process (like, say, the Woodburytype) that would have been much too expensive to use in a mass-market publication like SciAm. Also, the photographic plates in 1876/7 weren't quite up to the task of fixing an image exposed so quickly. Even when Worthington's book is published on this subject--a popular effort in 1895--it reproduces the photographs as halftones but there are still many interpretative drawings of those images. (The belief in the Civil War images reproduced as woodcuts in places like Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's was very high--it was enough to know the woodcut was being executed after a photograph and not from drawings made on the spot by the magazines' field artists.)

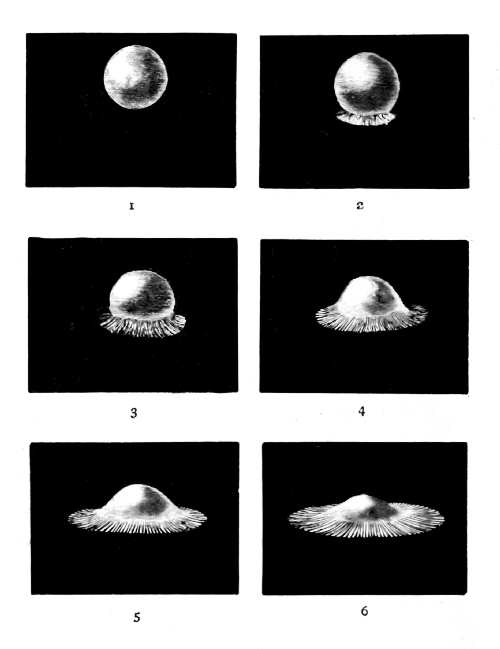

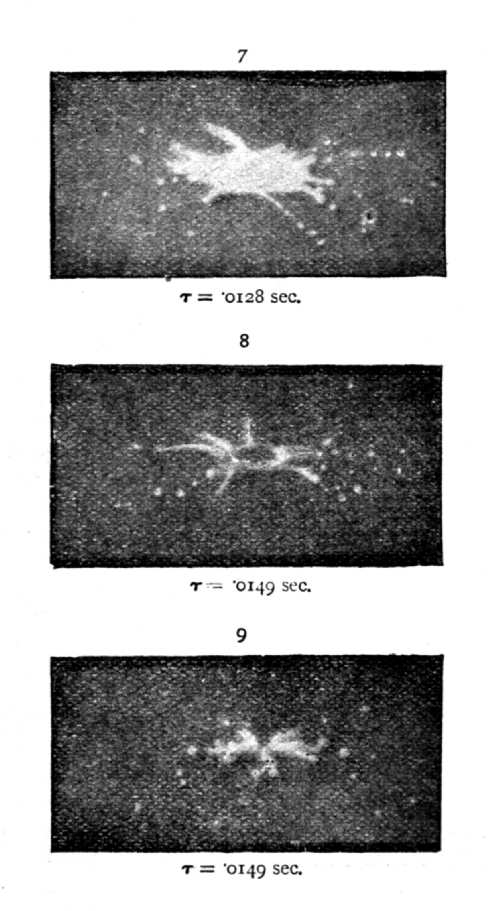

This was some pretty sophisticated stuff, being able to freeze the action of a drop of milk as it exploded in slow stages on a flat surface--especially, again, when you consider that photography wasn't yet 40 years old and was really only a half-decade or so into its first major revolution since the early 1850's.

Perhaps though the most spectacular thing of all about seeing this dedicated series of images of an exploding drop of milk was that you could look at the series and imagine it all taking place in reverse .

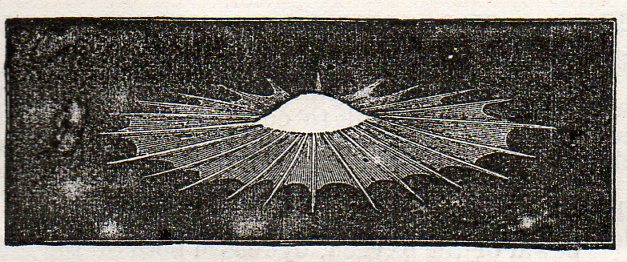

The drawings and photos below are taken from his 1895 work, The Splash of a Drop:

Comments