This post unexpectedly but now not unexplainably appeared on my blog this morning. It was written last night by Thomas Edison, and sent from 15 minutes in the past. He wanted to lay to rest the idea that there is no such thing as the afterlife. This might seem paradoxical that a ghostspirit was writing from the near-past about the impossibility of communicating with the dead, but he makes a strong case.

In his email Edison writes/wrote: "It's kinda like Olbers Paradox in a way: how can you have a dark night sky when there are so many stars? Well, that's because the universe is infinite and their light not; that's what it is like with the dead. As it turns out--surprisingly!--living people are finite but the dead are infinite, because we're dealing with the past possibilities and former universes. So the dead are everywhere but just don't have enough juice to be heard. Unless of course they have access to the internet, which is sort of like heaven, and which is where I now live, and which also offers the possibility of being dead in the future while being still dead in the past. Its good being multi-dimenional electricity."

Edison concluded with a picture: "You know what electricity looks like when you're inside it? Here it is1"

Thomas Edison did--once upon a time, in a land far far away--spark a world-wide semi-frenzy when he told a reporter that he was making a device that would be capable of detecting and perhaps even communicate with the dead.

Edison the agnostic, Edison the non-believer, Edison the anti-spiritual, was hardly poetic on topics of the soul (once referring in 1910 to the brain as a "meat mechanism"1a) and would never have wasted his time on such a thing as a device to detect the dead--unless it was all in fun, which is what this was. The old man was having a little wicked fun with a reporter, A.F. Forbes (later the founder of Forbes Magazine and father of the father of the failed and forever failing presidential candidate), who dutifully reported it ("Edison Working to Communicate with the Next World") in a 1920 issue of American Magazine. He said: “...I am inclined to believe that our personality hereafter will be able to affect matter. If this reasoning be correct, then, if we can evolve an instrument so delicate as to be affected, moved, or manipulated...by our personality as it survives in the next life, such an instrument, when made available, ought to record something.”2

The story, as they say, had "legs", and was re-reported many times, reaching even into the Scientific American: in 1921: "I don't claim anything, because I don't know anything.... for that matter, no human being knows" Edison said. "But I do claim that it is possible to construct an apparatus which will be so delicate that if there are personalities in another existence who wish to get in touch with us... this apparatus will at least give them a better opportunity."

Indeed.

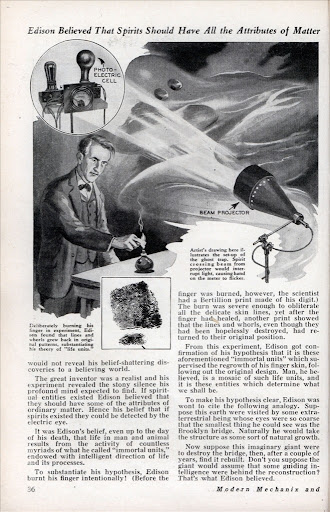

Later in 1921, A.D. Rothman for the New York Times wrote a story that had Edison constructing a machine that was sensitive enough to detect a bit of the "one hundred trillion" "life units" that pooted away from the body on death, and which evidently were (a) detectable, (b) capturable and (c) meant anything beyond being a+b.

I suspect that Edison (who once remarked that he didn't know what the word "spiritual" meant) was happy with this outcome, the world looking for him to turn the afterlife inside-out, to make it observable, feasible, concretized--to show that it existed. And who could blame them? Edison as an inventor and as a master of a group of 50 other inventors and advanced assistants had an enormous track record of revolutionary successes--why not this? Some of what he brought to bear on the world--electric lighting, the phonograph, and so on--must've seemed almost as deeply science-fictional as weighing the dead. Perhaps his conceit in this whole episode might've been in an attempt to show how similar the belief was in his "invention" to that of any (other) religion.

________

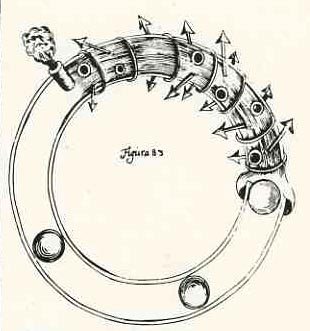

1) This illustration is actually from Praxis Artolleriae Pyrotechnicae, printed in Osnabruck by Tilman Buchholtz for Johann Georg Schwaender, is one of those beautiful books of horrible things; the "arrows" on this device of ear aren't showing the direction of rotation; they are actually spear tips looking for some flesh to tear.

1a) In an interview with Edward Marshall in the New York Times, 1910.

2) Beyond knowing that this was all outside of Edison's interests, we know it was a prank because he said so, in the New York Times, in 1926: “that man came to see me on one of the coldest days of the year...his lips were blue and his teeth were chattering...I really had nothing to tell him, but I hated to disappoint him so I thought up this story about communicating with spirits, but it was all a joke.” NYT, October 15, 1926, page 11. I'd reproduce the whole thing here but ProQuest seems to be yelling at its readers not to.

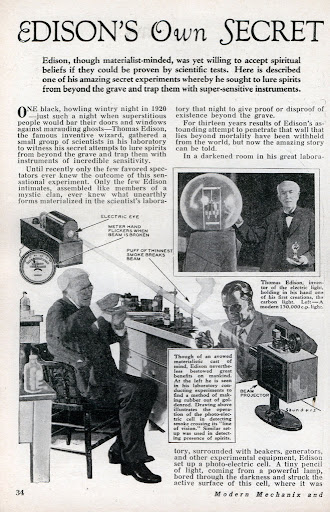

3) Here's a bit from Modern Mechanix (1933, two years after Edison's death):

Comments