JF Ptak Science Books Post 1320

I think that if a grown-up kid in 1940 was offered the chance to have a working-man’s Super Power,to be suddenly endowed with a non-heroic Super Something, a popular choice could have been to possess radio repair vision (RRV). Or that’s what it seems like. The popularity of radio was so fantastic that ownership of radio sets doubled in the United States from 1931 to 1938, when houses with radios rose from 40% to 80%. Radio was everything. There were many contributory factors to this phenomenal increase in popularity, not the least of which was the Great Depression–once you got your radio the listening was basically free except for the power that it cost to run the radio. Recorded disks on the other hand suffered tremendously, with sales falling from $75 million in 1929 to 23 million in 1938 (with a low point of $5 million in 1933), and that would be due to the Depression and the the popularity of free stuff on the wireless, as well as other things.

I think that if a grown-up kid in 1940 was offered the chance to have a working-man’s Super Power,to be suddenly endowed with a non-heroic Super Something, a popular choice could have been to possess radio repair vision (RRV). Or that’s what it seems like. The popularity of radio was so fantastic that ownership of radio sets doubled in the United States from 1931 to 1938, when houses with radios rose from 40% to 80%. Radio was everything. There were many contributory factors to this phenomenal increase in popularity, not the least of which was the Great Depression–once you got your radio the listening was basically free except for the power that it cost to run the radio. Recorded disks on the other hand suffered tremendously, with sales falling from $75 million in 1929 to 23 million in 1938 (with a low point of $5 million in 1933), and that would be due to the Depression and the the popularity of free stuff on the wireless, as well as other things.

People maintained their radios, kept them in good order, tinkered with them, cleaned the tubes, replaced the tubes, kept things going. Those early units were pretty hearty, overall, but there was a certain percentage of folks who couldn’t do the basics for themselves, and so would bring in their radio repair man. He was an important fixture in a community–not quite like the milk man or the ice man, who would be seen everywhere every day, but popular enough. TO be able to fix radios with supervision and kept millions of people connected would’ve been a big deal, especially if you thought about it with the mind of a ten year old.

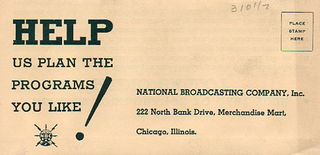

I’m just trying to establish the popularity of radio with this aside to get at the main point of this post–how radio executives at NBC tried to access the common knowledge base of what people wanted to hear on the radio, and when. And one aspect of that was seen on this single piece of paper: [The original is available for purchase at our blog bookstore.]

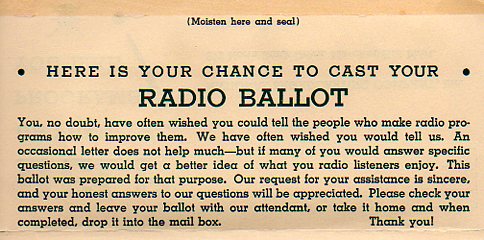

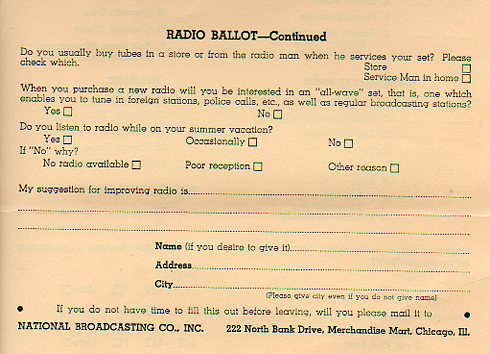

The National Broadcasting Company sent out self-adhesive mailers to people to probe their listening needs. This would seem prehistoric by today’s standards of estimating what television/video watching people were like and what they would want to see, and perhaps to pay for. But in 1940*–or perhaps a little earlier–this was one method of making this determination, with a gentle survey about what the listener wanted to hear, and when. And they were expected to pay for the privilege, as well, as these self-,mailers weren’t pre-stamped.

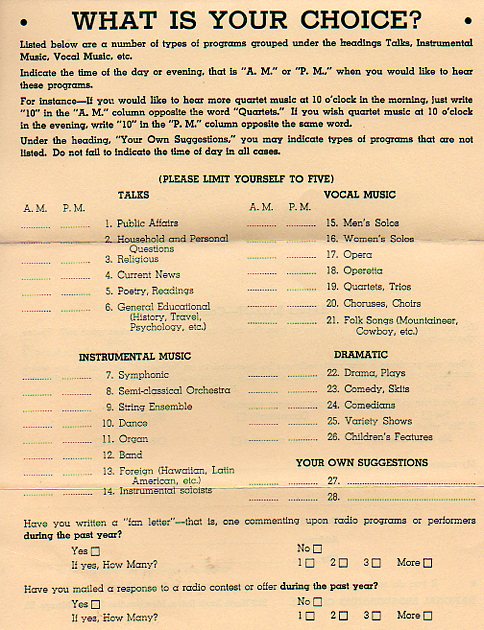

On the questionnaire of listed types of programs we find 26 examples, including six for “talk radio”, sixteen for music (eight for instrumental and seven for vocal!), and then only five for the dramatic stuff (comedy shows, drama, variety shows, and even one for children. (An historian of radio programming would probably know instantly the age of this flyer given the number of slots slated for the drama shows, I’m sure.) The division of the music is also interesting, particularly for me since "string ensemble" is one of the 26 overall programming selections, though I doubt that they were talking about the late quartets of Beethoven--I think they might have been referring to sweeping, thousand-string "beautiful" music. Also the division of "opera" and "operetta" is unusual.

The "brevity" part of listen surveys is certainly attained here--the complexity part will come a little later. Radio surveys became very sophisticated in the mid-1950's when radio's existence was threatened by television, which completely dominated the market for talent and advertising dollars and listeners by the late'50's.

Notes

There’s no direct mention of FM radio, which came into some restricted use by 1938-1940 and which is not mentioned explicitly here. Perhaps this means that this was issued before FM–or perhaps it is later, as I said, and simply just not mentioned.

Comments