JF Ptak Science Books Post 1131

Finding the hard-to-find, the invisible, the "hidden", is an essential aspect of, well, mostly everything. Whether it is Newton separating light with a prism to find its constituents, or Hooke investigating the formerly quasi-real microscopical world to reveal worlds within worlds, or Galileo using his telescope to quash the ideas of the unaided-eye-visible night sky as an unaltering perfection of creation, or Roentgen seeing through his wife's skin, or Fraunhoefer finding the complex spectrum, or Henry Draper determining a chemical constituent of the sun, or the invention of the zero or negative numbers or subtraction, of finding Black Holes or other planets or the remnants of the Big Bang, or (Kandinsky) finding the nonrepresentational aspect of art, or Duchamp finding in an upturned urinal that art had no boundaries...the list goes on and on.

One aspect of this "finding something in nothing" business that is interesting to look at because it is so local and discernible--and recent--is in air navigation and detection. And I'll do this using a series of excellent illustrations from The Illustrated London News, all of which are from the 1927-1938 period.

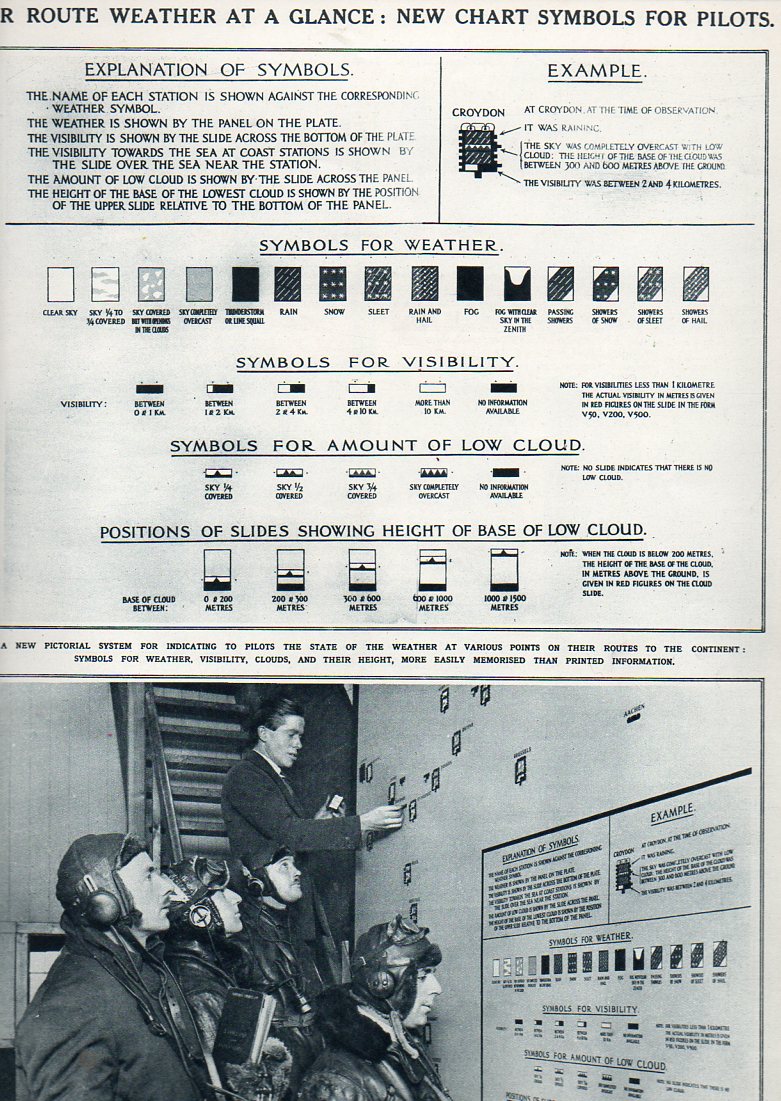

The first is relatively simple, at least simple from here in the year 2014, which shows four pilots being briefed on weather conditions with a aerial chart for conditions along intercontinental routes. The placement of these symbols represented a vast improvement over the earlier systems of readying pilots for what weather lay ahead, if indeed there were any communications at all. This represents an early look at a codification of conditions and expectations for air travelers--a display of new and important data in 1927.

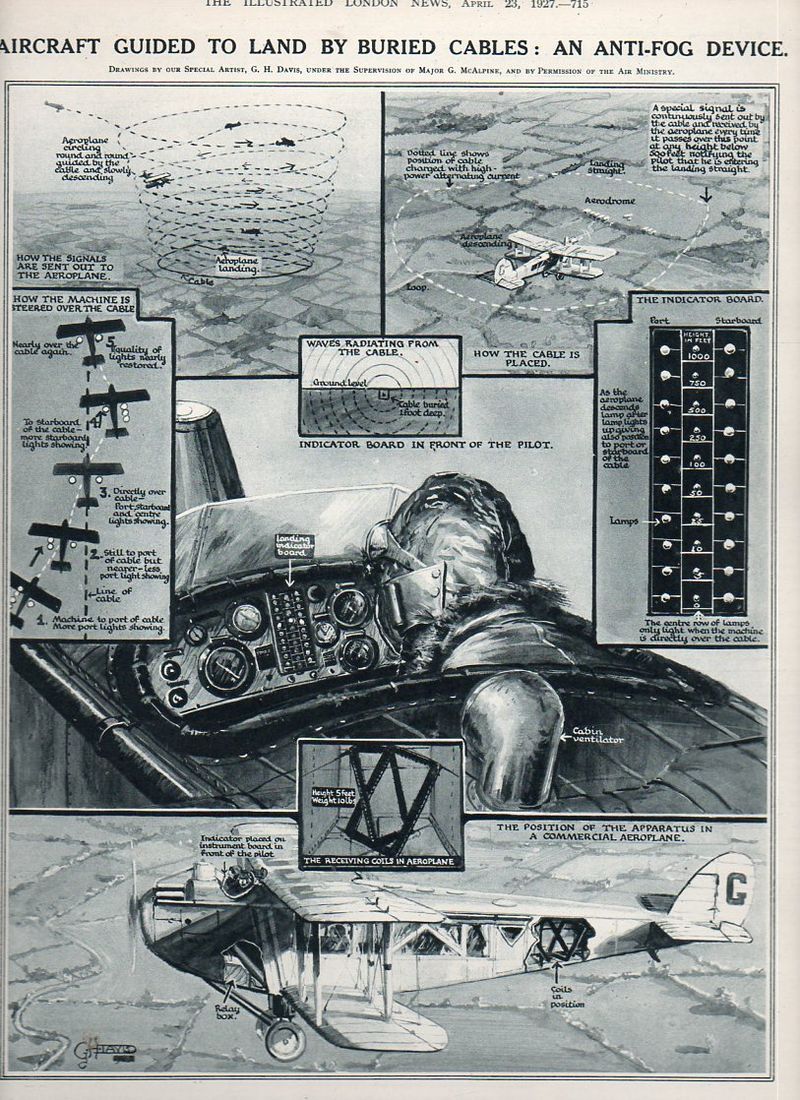

Next is a brilliant device for assisting pilots to land in foggy and dark conditions--actually on how to find the ground safely. In 1927 (again) a RADAR-like system was put into place on aircraft that involved receiving the signals of an ac-pulsed buried electrical cable that surrounded an airport. The receiver (seen here on the flight panel of the pilot in an open-air cockpit) would be read to reveal proximity of the airport, the pilot making wider and then closer spirals in descent until his was basically within the buried airport cables and thus able to land.

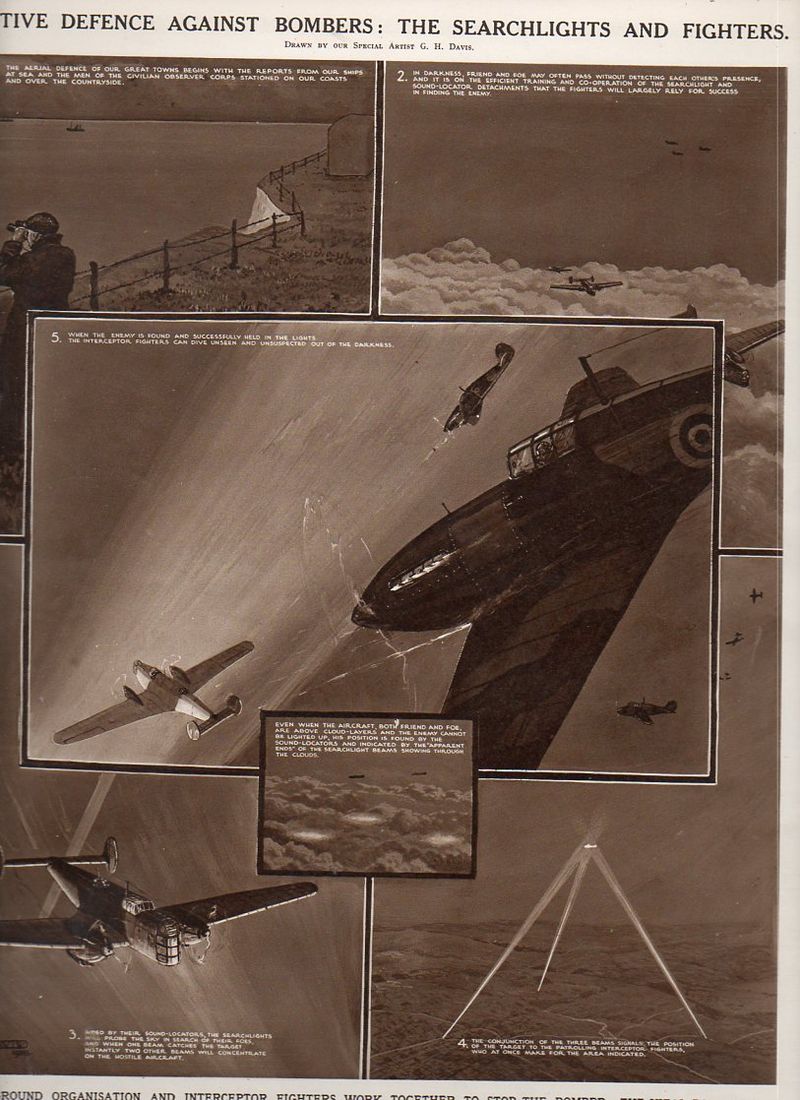

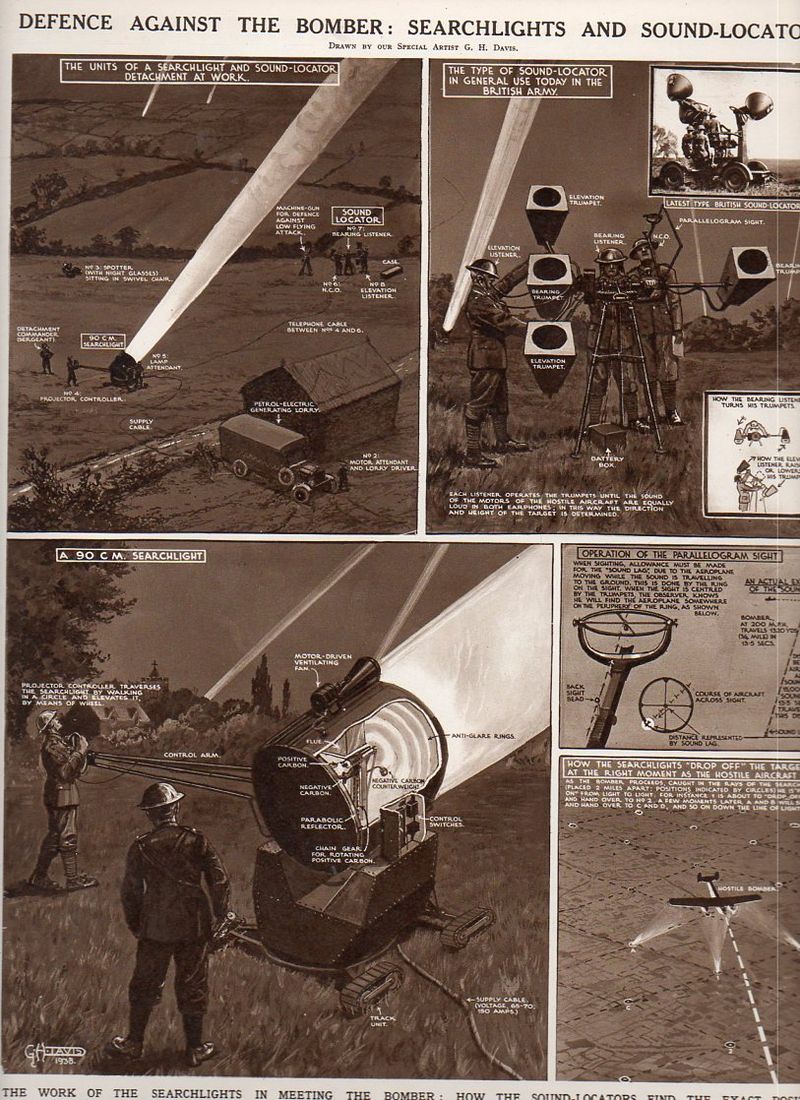

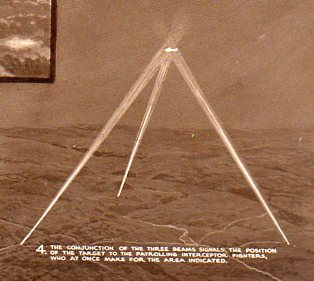

Prior to WWII RADAR1 was somewhat functional but still in development, and as we see in this set of 16 July 1938 illustrations, the key methods for finding enemy aircraft at night (in order to shoot it down of course) was an audio-visual method, using "sound-locators" to find the approaching bombers and then spotlights to illuminate and track them to their destruction.

These images represent some idea of the state of the art of being able to find things--like the ground at night or approaching enemy aircraft--in the 1927-1938 period, all of which would be drastically changed in just the next two years.

NOTES

1. RADAR was coming very close to being developed in the early 1930's--and in 1935 the process of experimentation and implementation was at a peak. The development of this new technology was an international property, though perhaps no one owned it more in this period than the British, with Watson Watt giving his experimental ideas on RADAR to the Air Ministry on 12 February 1935 in a secret report titled "The Detection of Aircraft by Radio Methods". Int his years alone there was feverish work being done by Rudolf Kühnhold (Scientific Director at the 'Kriegsmarine Nachrichtenmittel-Versuchsanstalt) who in 1933-1935 established a RADAR-hunting company called Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische und Mechanische Apparate, or "GEMA"; there was also elements of the Royal Navy, Telefunken, Standard Elektrik Lorenz, Philips Company's (of Eindhoven, Netherlands) Natuurkundig Laboratorium, the Research Office of Nippon Electric Company, and even in the Soviet Union (until the key figures involved were murdered in Stalin's purges--this one distinguished from others and referred to now as The Great Purge-- of 1937), the French Compagnie Générale de Télégraphie Sans Fil (CSF), and the Italian Regio Instituto Electrotecnico e delle Comunicazioni (RIEC, Royal Institute for Electro-technics and Communications) to name a few. The United States of course had been long working on the project, at least since 1922 at the NRL, with considerable private (and federally funded) work done by RCA

.

Whipping ahead into WWII a very significant "battle of the beams" began between the U.K. and Germany, especially during the Battle of Britain, involving countermeasures, espionage, propaganda and false-positives in regards to the use and development of radio-based tracking and detection--the U.K. particularly making use of this technology in a wide-spread air defense system. But it was in the United States in 1940 (and really by the U.S. Navy) that RADAR got its name (for RAdio Detection And Ranging) as well as its great impetus for development and deployment.

Comments