JF Ptak Science Books Post 1165

One morning Tim was rather full

His head felt heavy which made him shake

He fell off the ladder and he broke his skull

And they carried him home, his corpse to wake

Rolled him up in a nice, clean sheet

laid him out upon the bed

With a bottle of whiskey at his feet

And a barrel of porter at his head–Tim Finnegan’s Wake, ca. 1850's.

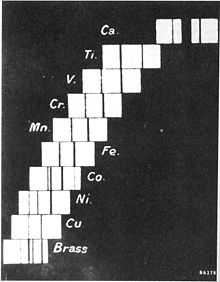

The whole pursuit of ladders here today comes from looking at something described as a ladder but really isn’t one: Henry Moseley’s famous “ladder diagram” from a 1913 paper establishing the important Moseley’s Law (establishing the atomic number as a measurable experimental quantity). A more concrete ladder-like diagram is found (beginning about 1885) is the diagram used for displaying readouts from electrocardiograms. On the other hand, the ladder from which Tim Finnegan fell in the 19th century Irish ballad (from which Mr. Joyce drew his inspiration for his last book from 1939, dropping the possessive apostrophe) was a real ladder, but neot necessarily nuts-and-bolts real.

There are of course monster ladders–like the ones that reach 1300' high inside transmission towers. There were long ladders that reached up the sides of massive funnels of ocean-going ships, and short ones leading to the cockpits of fighter planes. There’s a very short ladder that reached down only eight feet or so, but that one was on the side of the LEM of the Apollo 11, and the LEM was on the Moon, which may be our furthest-away ladder. There were other 19th century versions of far-away ladders–these belonged to some of the early aeronauts and their balloons, some of which held some very large passenger cabins, some of which had two storeys, complete with ladders.

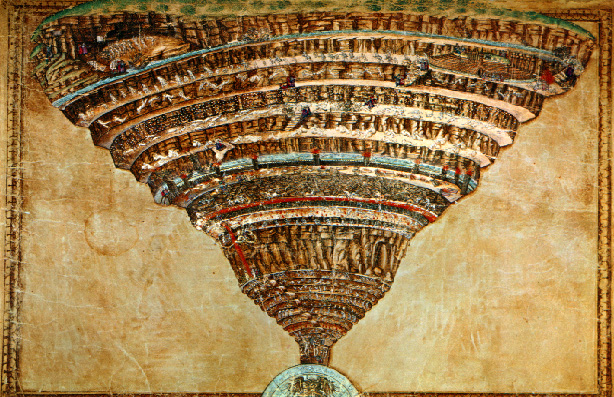

The most famous of all ladders is probably Jacob’s ladder, an account of the patriarch’s dream of entering Heaven as found in Book of Genesis (28:11–19). On the other hand, the image painted by Sandro Botticelli, led the other way, south, deep south, to Hell. William Blake chose to represent another more beneficent ladder, again leading the aspirant to Heaven. And speaking of painters, the elder Brueghel included ladders in minor appearances in a number of his paintings (like “Big Fish Eat Little Fish”, and Hunters in the Snow”).

William Shakespeare wrote of a gentleman’s knowledge of rope ladders, which of course could be found all over masted ships throughout history–and indeed the ladder stretches all the way back in human history, reaching back to cave paintings that dat from the 11th century BCE.

There are plenty of metaphorical ladders like “climbing the corporate ladder”, or hope for glory and success and victory in simple Chutes and Ladders. And then of course, what better way to end a short look at ladders than with lovely lovely Ludwig (the other one):

“My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.) He must surmount these propositions; then he sees the world rightly.” --Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 6.54

Moseley's Ladder:

Botticelli's Hell:

Comments