JF Ptak Science Books Post 1145

{This is one in a longish series on the the History of Blank, Empty and Missing Things]

There is importance and elegance, grace, necessity in nothingness. That nothing happens is exceptionally important in almost all areas: the meaning of silences between notes and longer pauses in musical compositions, the essential aspect of timing in a comedic routine, the special place that one goes in meditation, the distinction of wide margins in a beautifully designed book (magic that hasn't been remotely approached by Kindle & Co., though it said that they have their own hidden beauties), and sometimes just the place where ideas are born. The places for the beauty of nothing are endless.

The use of nothingness in art compositions an designs is of course essential--it is sometimes just a little odd to think of it as its own special, spatial element, as its own force of creation or design.

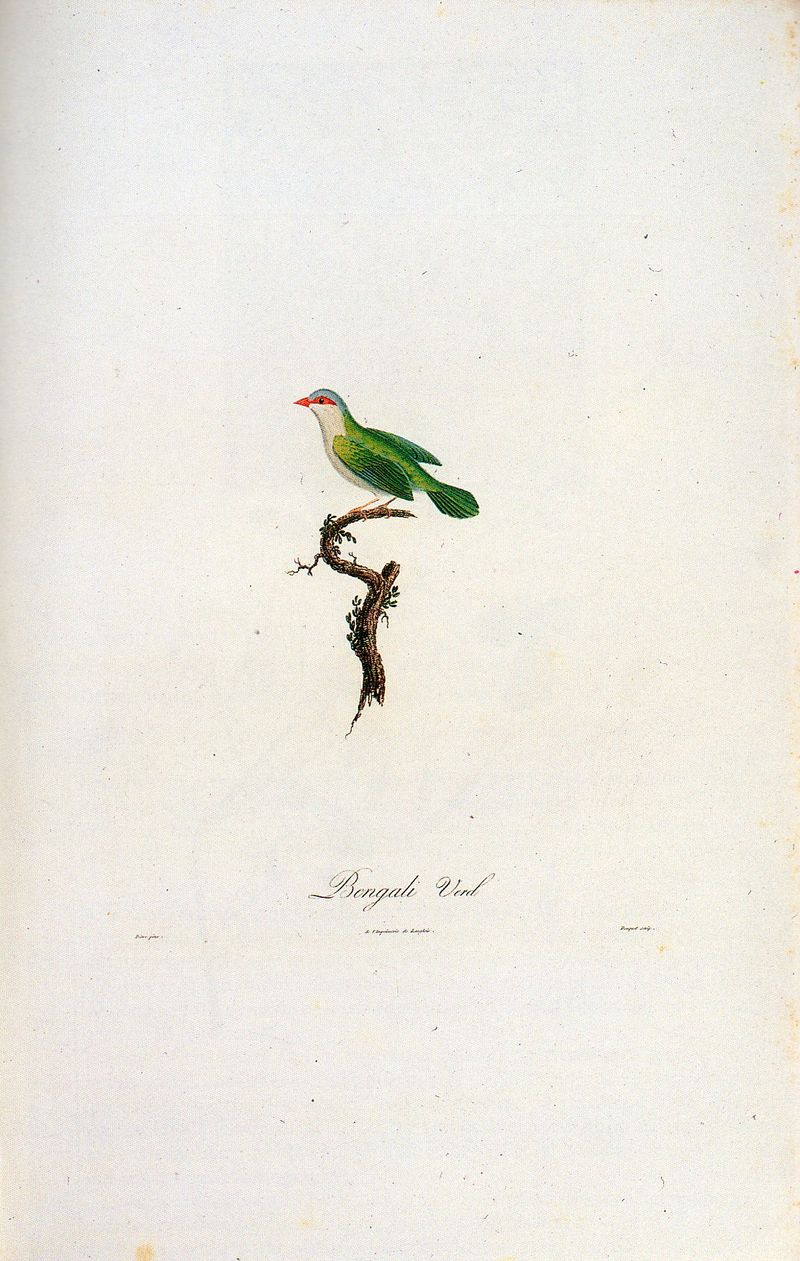

Take for example this beautiful use of not filling up space by Louis Jean Pierre Vielliot in his 1805 work on natural history:

It would be so easy to crop out these gorgeous margins, and so kill the power of this image--you're left with the main ingredient of the effort, but without its necessity, or power.

And of course there's sometimes everything in nothing, seen here, with the universe in the hands of the Primum Mobile, (one image among 50 in a series known as the Mantegna Tarocchi,

drawn and engraved by artists unknown ca. 1465, though it was once

believed to be the work of the great master Andrea Mantegna (and later

the possible work of Bacci Baldini)). From my reading of this image, the universe is held in the hands of the primum mobile,

a spherical container of not-quite-nothing, waiting for the creator to

breathe life into it. The possibility of absolutely nothing was seen as

an impossibility, a perfect vacuum, a space of certain nothingness, was

a violation of theological belief. That the sphere existed was a proof

that–in the 15th century–you simply couldn’t have a container of

nothingness. The very presence of the sphere confirming that there was

something being contained by it.

And of course there's sometimes everything in nothing, seen here, with the universe in the hands of the Primum Mobile, (one image among 50 in a series known as the Mantegna Tarocchi,

drawn and engraved by artists unknown ca. 1465, though it was once

believed to be the work of the great master Andrea Mantegna (and later

the possible work of Bacci Baldini)). From my reading of this image, the universe is held in the hands of the primum mobile,

a spherical container of not-quite-nothing, waiting for the creator to

breathe life into it. The possibility of absolutely nothing was seen as

an impossibility, a perfect vacuum, a space of certain nothingness, was

a violation of theological belief. That the sphere existed was a proof

that–in the 15th century–you simply couldn’t have a container of

nothingness. The very presence of the sphere confirming that there was

something being contained by it.

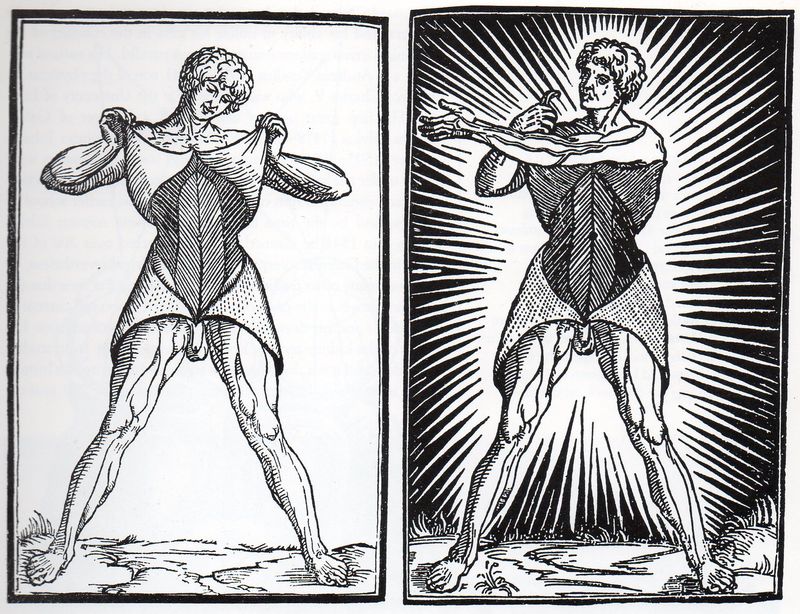

Here's an excellent example of the use of nothing as a design force (from Berengario da Carpi's Commentaria siper Anatomia Mundini, published in Bologna in 1521), where we see what is basically the same exact dissection, except for changes in the internal shading and of course the lightning bolt background. The simpler design is by far the superior.

It does take some confidence and courage sometimes to use big wide swaths of white, using complementary nothingness--and that's a good thing. Sometimes too much "something" isn't nearly as useful or important as a little bit of "nothing".

Comments