JF Ptak Science Books Post 1107

I’ve written a number of times about Vannevar Bush in this blog. He was a brilliant, practical, deep-sighted Yankee of an old school, capable of selecting the correct course of action and getting to it, his quiet resolve apparent to everyone. He also had a large part in the winning of WWII, being in charge of scientific and technical development for military and war-related affairs, deciding how to spend time and effort and money for the best possible result to win the war (That would be the OSRD, the Office of Scientific Research and Development, which he headed, and created–actually he outlined the whole thing on one sheet of paper and had the mammoth idea approved by President Roosevelt in a quick 10-minute session in 1942.)

I’ve written a number of times about Vannevar Bush in this blog. He was a brilliant, practical, deep-sighted Yankee of an old school, capable of selecting the correct course of action and getting to it, his quiet resolve apparent to everyone. He also had a large part in the winning of WWII, being in charge of scientific and technical development for military and war-related affairs, deciding how to spend time and effort and money for the best possible result to win the war (That would be the OSRD, the Office of Scientific Research and Development, which he headed, and created–actually he outlined the whole thing on one sheet of paper and had the mammoth idea approved by President Roosevelt in a quick 10-minute session in 1942.)

He had a brilliance to him in choosing the important stuff that was necessary and the important stuff that could wait. For example, he told Norbert Wiener that the war needed to be won before investing in the challenge to develop the digital computer–it just wouldn’t be developed quickly enough, he felt, to do the jobs necessary to substantiate its time and effort before war was won.

He also could say “no” to Einstein, a man who he admired and respected, but also a man who he thought he could not trust with the development and construction of the atomic bomb. As much as he wanted to share the project with Einstein, he couldn’t, and wouldn’t, and didn’t. And he had a point.

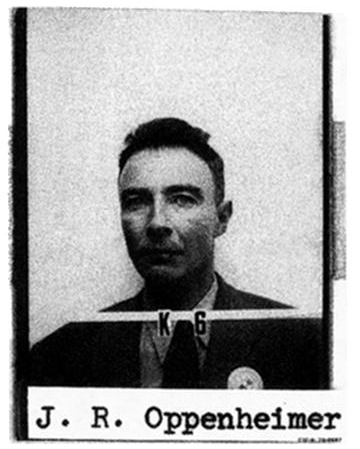

He stood on tall ground in regards to Oppenheimer when the witches went to gather Oppenheimer's soul. At a time when major forces decided that Oppenheimer must go, that he should be excluded from Q clearance and from being involved with the development of the thermonuclear bomb–and that he must go because he was seen as a security risk because of a series of minor incidents (like light associations with the Communist Party in the 1930's), Bush would have none of it. Mostly, Oppenheimer represented a threat to political desires for the development of new weapons, not so much, really, as a possible Soviet agent. Bush supported Oppenheimer, and questioned the entire legitimacy of the hearings themselves.

“Here is a man who is being pilloried because he had strong opinions, and had the temerity to express them", Bush said, ending his testimony with this forceful statement:

"I think this board or no board should ever sit on a question in this country of whether a man should serve his country or not because he expressed strong opinions. If you want to try that case, try me..."

Many of course stood by Oppenheimer; Bush’s support seems to me to be among the strongest. Perhaps even more pissed than Bush was I.I. Rabi, who in disgust of the proceedings said: “"He is a consultant, and if you don't want to consult the guy, you don't consult him period...We have an A-bomb...and what more do you want, mermaids?"

There was also John Lonsdale, chief of security for the Manhattan Project and who investigated Oppenheimer thoroughly, as he said during the hearings: "We kept him under surveillance whenever he left the project. We opened his mail. We did all sorts of nasty things". Lonsdale firmly believed in Oppenheimer, thought him innocent in this ‘non-trial”, and defended the man throughout the rest of his long life (dying at age 95 in 2003).

Others of high importance questioned Oppenheimer’s integrity, patriotism and trustworthiness:

“More probably than not, J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union", William L. Borden.

"I would not clear Dr. Oppenheimer today", Leslie R. Groves (the military version of Oppenheimer, a brigadier who could work with Oppenheimer during the war but who now felt him to be in the way.)

“We have...been unable to arrive at the conclusion that it would be clearly consistent with the security interests of the United States to reinstate Dr. Oppenheimer's clearance", Gordon Gray.

Edward Teller hunted Oppenheimer down during the hearings, killing him with quiet verbs, but killing him nonetheless:

“Q. Dr. Teller, you know Dr. Oppenheimer well; do you not?

A. I have known Dr. Oppenheimer for a long time. I first got closely asso-ciated with him in the summer of 1942 in connection with atomic energy work. Later in Los Alamos and after Los Alamos I knew him. I met him frequently, but I was not particularly closely associated with him, and I did not discuss with him very frequently or in very great detail matters outside of business matters.

Q. To simplify the issues here, perhaps, let me ask you this question: Is it your intention in anything that you are about to testify to, to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States?

A. I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite.

Q. Now, a question which is the corollary of that. Do you or do you not believe that Dr. Oppenheimer is a security risk?

A. In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act-I under-stood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more.

In this very limited sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel personally more secure if public matters would rest in other hands.”

In a mealy way, Teller found Oppenheimer loyal, but susceptible to outside influence, and thus should no longer be trusted with the high level secrets that had been his very persuasive metier.

In conclusion, the commissioners rendered their decision against Oppenheimer, fearing to let the man who ran the Manhattan Project do anything of significant secrecy for the U.S. government:.

STATEMENT BY THE ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION

[For immediate release June 29, 1954] “Decision and Opinions of the United States Atomic Energy Commission in the Matter of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer.”

“It is clear that for one who has had access for so long to the most vital defense secrets of the Government and who would retain such access if his clearance were continued, Dr. Oppenheimer has defaulted not once but many times upon the obligations that should and must be willingly borne by citizens in the national service.”

“Concern for the defense and security of the United States requires that Dr. Oppenheimer's clearance should not be reinstated.”

“Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer is hereby denied access to restricted data.”

LEWIS L. STRAUSS, Chairman.

EUGENE M. ZUCKERT,* Commissioner.

JOSEPH CAMPBELL,* Commissioner.

In any event, the Oppenheimer Hearings are a long, tangled tale, much more than I coul dexplain in this short post. I did just want to bring up another facet on strength and character from a heroic man who we hear little about: Vannevar Bush.

Comments