JF Ptak Science Books Post 1103

Talking to the Future: a Note of Pity to Ourselves in 300 Generations

In the history of words I’ll take a wild guess and say that fractions of 1% of everything communicated is directed at ourselves in the future–or at least it has the possibility of being directed to someone else when our deeds are long, long since forgotten.

And by writing to the future I don’t mean in an off-hand way, our words being read in 12,010 by chance, idea archaeologists looking at what people were talking about 10,000 years earlier; and I don’t mean via “reconstructing” our radio or tv broadcasts (in the not-right Jodie Foster Contact kinda way). I mean intentional messages to be read a long time from today.

A more problematic entry would be images and symbols design to be read by future generations, in the deep future. This is not a very deep category, though a famous (if not well designed) example being the one associated with Carl Sagan that was attached to the 1972 Pioneer 10 and 1973 Pioneer 11 spacecraft, which attempted to explain what humans were should either vehicle in any eon come into contact with other-than-Earth life.

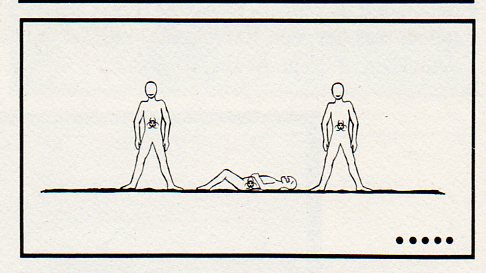

Another is the pictograph presented here, which appeared on page 117 of the ironically and extraordinarily-titled Reducing the Likelihood of Future Human Activities That Could Affect Geologic High-Level Waste Repositories1, the first half of which (bolded above) could make a nice departure for some other science fictiony type story. But what these folks were talking about, plain and simple, was how to prevent future generations from digging into or other disturbing in any way buried masses of nuclear waste.

Another is the pictograph presented here, which appeared on page 117 of the ironically and extraordinarily-titled Reducing the Likelihood of Future Human Activities That Could Affect Geologic High-Level Waste Repositories1, the first half of which (bolded above) could make a nice departure for some other science fictiony type story. But what these folks were talking about, plain and simple, was how to prevent future generations from digging into or other disturbing in any way buried masses of nuclear waste.

This pictograph is meant to be a non-linguisitc, universally-understood warning to future generations that the ground they are standing on is above a nuclear waste storage site. The plan was that nuke waste would be solidified and buried in rock hundreds of meters below the surface in an effort to keep in line with governmental policy of waste disposal2. The pictograph relates to the restricting of future human activities part of the title of the work in question–that is, folks in the future who might muck around, drilling, into the nuclear waste site. This pictograph tells them why they shouldn’t do so, because of all of the terrifically lethal mojo underground.

As one might guess by the title, the report has its own communication problems–it is dense, turgid and not a particularly clear document. It is a fine document illustrating the problems of communication, but not in the way it would have wanted to be, celebrating a reverse triumph in a Darwin Award/IgNobel type of way. And all of this in spite of/or because of a healthy slice of linguists, semioticians, logicians, artists, graphic designs, politicians,. sociologists and so on constructing the thing.

The sign basically says that if you drill at this spot (to some unspecified depth) through aquifer or underground stream or water source or something that some point you may reach the biohazard nasty, which will then get into the water supply and into humans, which will then kill them.

The sign was designed for 10,000 years hence, and depended upon pictures to convey the message rather than words (except for H20, and the biohazard symbol). Of course the radioactive nastiness will be there for millions of years, which would be an entirely different story in terms of imaging. Perhaps.

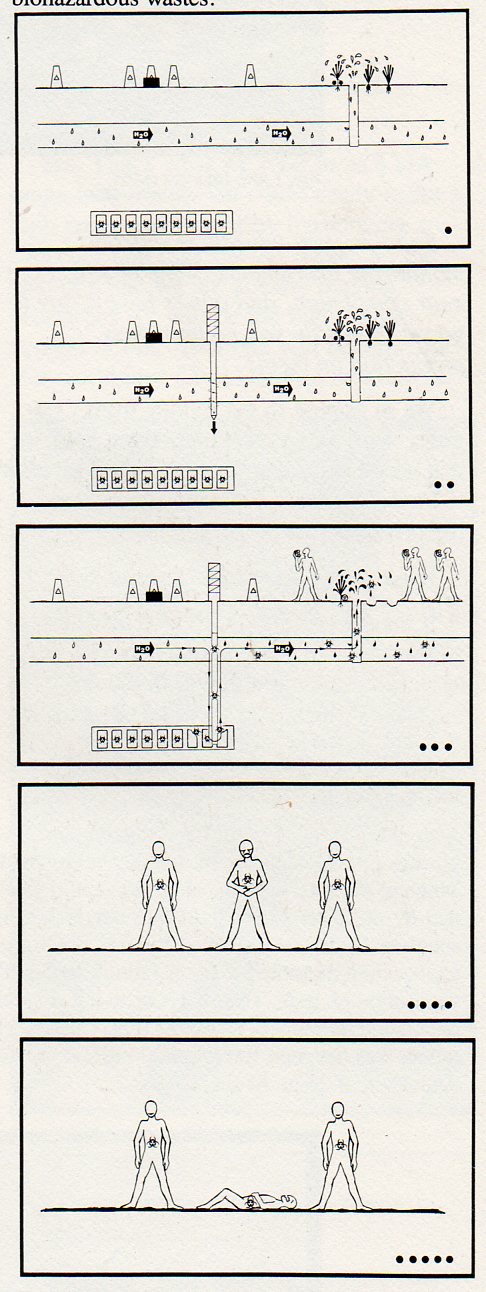

The one thing the design of the pictograph has in its favor is that it is read top to bottom--no language on Earth (so far as I know) is read bottom to top, though there are many differences in reading right-left/left-right. Beyond that, the pictograph stumbles over itself--except for the last two images, which may or may not tell someone that something bad is happening.

There are plenty of time capsules and idea-vehicles to the future--I'm saddened that this was seen to be one of the essentials that we would pass on to our future selves.

Notes:

1. Reducing the Likelihood of Future Human Activities That Could Affect Geologic High-Level Waste Repositories (Technical Report prepared for Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation, Battelle Memorial Institute; BMI/ONWI-537; May 1984)

2. “Present society's responsibility is to dispose of radioactive wastes in a manner that is safe, is environmentally acceptable, and does not require long-term maintenance or surveillance. This ground rule is consistent with the objectives in the U.S. Department of Energy."Reducing..., page 2.

The pictograph, explained, pp 115-116 from Reducing....

The pictograph...was developed using the concepts and guidelines discussed by Givens (1981). The objective is to convey to the reader the sense that if the area below the markers is disturbed, toxic substances will enter the ground water and lead t o severe consequences. relies on several visual images acting in concert to relay the message.

The ground surface exhibits peripheral markers and a central monument to denote relevance to the site where those markers and monument exist.

The ground-water system is indicated by water-drop shapes and by the chemical symbol for water (the only departure from icons, used as a redundant measure).

A repository far below the surface is depicted with the biohazardous symbol. The fact that the object portrayed below the surface is a repository may not be at all evident to a future reader from the first frame; however, the movement of the dark material from the repository through the aquifer and into the vegetables in the third frame, coupled with the movement of the biohazardous symbol, should imply the burial of biohazardous materials below the surface.

The pictographic sequence exaggerates reality with regard to the rapidity of contaminant transport and uptake, and with regard to the severity of the consequences. However, exaggeration is necessary because both the clarity and the relevance of the message may suffer if.the pictograph attempts to indicate contaminant transport time of thousands of years. Similarly, the consequence portrayed, a painful death, over-exaggerates the cause-effect relationship and the rate of the individual's demise (one out of three suffer death in the pictograph, whereas a

to chance would be more representative).

I never could understand the foofaraw over warning future generations about manmade underground nuclear hazards. There are plenty of natural nuclear hazards that can cause trouble if you drill into them. Future generations will probably have to deal with that a lot more often than manmade hazards. I suppose this study was more of a remedy for unemployment hazards encountered by contemporary semioticians, logicians, sociologists, and their ilk.

Posted by: Charles | 03 August 2010 at 08:28 PM

It is not possible for me to imagine 10,000 years hence--that's already basically about twice all of recorded human history. I suspect this future biz would be as dense to us as the year 2000 would've been to someone educated in 2500 BCE. But that's not the point, really, with what I was writing about--mainly I was just interested in the first half of the title of the pamphlet I was moaning about.

Posted by: John F. Ptak | 03 August 2010 at 08:50 PM

It is thoughtful to try to leave a warning about stunningly toxic bundles of waste, but it IS hard to imagine 10,000 years hence. Will we already be well aware of what's down there, perhaps even have a solution, or will we be hunting dog-sized rats on foot with spears tipped with broken Coke bottles? The pictures are probably best, but at first glance, I thought the last one was a Pilates class.

Posted by: Jeff Donlan | 04 August 2010 at 10:14 PM