JF Ptak Science Books Post 1091

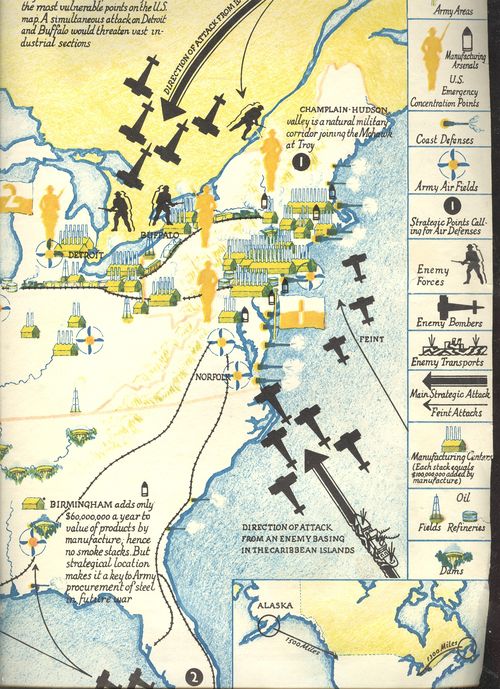

I was reading an early post that I made here (“The Invasion of America, 19??--1935--Scenario for Invasions via Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean"), mainly concerned with the fantastic, propagandistic map that accompanied the original 1935 Fortune magazine article. This time I took away something entirely different.

The article, “Why an Army?”, asked the interesting and surprising question of whether the United States actually needed a standing army. The army was supposed to be for defense, and the author adroitly points out that the U.S. had never fought a defensive war–except, of course, if you redefined certain ideas and terms that could somehow explain the wars for Manifest Destiny (the Mexican-American war of 1846) or the Spanish-American war (1898) and so on as “defensive” in their provocatively offensive manner as a reverse defense procedure. But more on that in a bit.

What really surprised me was the appearance of the phrase “...the effect of an expansion of this nuclear force...” It simply referred to the standing army size of 165,000 troops there in 1935, but ten years later it would mean something entirely different.

This is when I was thinking of the enormous changes that took place in the ten-year period of 1935-1945. And then of different ten-year periods–but first to WWII.

In 1935 the “nuclear” that was being referred to was the crux of the American fighting force, which was a standing army of about 165,000 men and 1,509 airplanes (“of all types”). At this point the U.S. Army was poorly outfitted, costing a total of 1 million dollars a day for upkeep and maintenance. The technical, ordnance aspects of the army’s mainstays were unimpressive. The great standard cannon was the 75, an 1898 French-created thing capable of a 6-degree traverse and which needed a massive pit for its recoil. WWI tanks were still a common sight, being replaced by the T1 “combat car”, a relatively-lightly armored fighting vehicle that was slow and underpowered. The T1 was just at this time being replaced by “the holiest of holies”, the T2, a much faster, somewhat better-armored and more heavily gunned (having two 30 calibers and 1 50 caliber) version of its earlier incarnation. It could travel 50 mph with its tracks on (unlike the T1, which, when it needed to move with some speed, needed to remove its tracks and replace them with wheels, and then vice versa once they got to the combat area). The T2 could run circles around the T1, and double (or triple) that around the 1000 or so WWI 6 mph leftovers. The problem was, though, that in 1935 there were only 19 of the T2's around–their $26,000 price tag was a bit much.

The discussion of increasing the “nuclear” force was to increase the standing size of the army-- ten years later the term could be used to describe an increase in the development of the first generation nuclear weapons, these following an absolutely phenomenal ramp-up for development and production of all manner of weapons during America’s involvement in WWII. It was an overall astonishing achievement that was capable of no other country on earth, given the vast resources and workforce in the U.S. This production was simply impossible for any other country to even approximate, especially when you consider the vast calls on energy that the production of the atomic bomb called for–and of course considering that America was a fortress, basically impregnable from any outside force.

Which gets us back to the Fortune article. The author references a Lloyds of London report that there were 500-to-1 odds that anyone would attack the U.S. in 1935 or in the near future. There really wasn’t anyone around with the power or wherewithal to do so, except for Great Britain, which of course would have no interest in doing such a thing. (Especially when you consider that the great natural resource wealth of GB was in the empire, and it was in the policing and protecting of the empire that required the attention of the Royal Navy and Army. Be that as it may, Britain was no going to attack America.)

The author of “Why an Army” makes the point that if the U.S. has an army it is for defensive purposes; on the other hand the U.S. has never really fought a defensive war. The idea of “defense” though needed to be expanded to include attacking other countries whose actions threatened our way of life. And so, “If the citizen thinks that he is ever going to need an army for meddling, then he needs one now”, given the poor state of American defense. “We cannot abolish the army if we think illogically that we will never be in a war”, the article claims, and “a war in any quarter of the world may affect our industrial mechanism...”

“We are no longer isolated and we have never been really holy...” Fortune concludes, and that the bottom line was that we needed a real standing army–not the make-believe sort that existed in 1935–if we were going to protect ourselves against invasion by attacking people who threatened our existence. [It is curious to note that there is no mention of Nazi Germany whatsoever in the course of this long feature article.]

And this winds up back to the history of ten-year periods of enormous change. I can think of some obvious examples:

1905-1915 for physics, 1911-1921 for the arts, 1945-1955 (for entering into the Cold War, MAD and the Korean War, not to mention the advent of computers and DNA and all the rest), 1859-1869 for Darwin, and spectroscopy and the maths, 1953-1963 for the enormous changes in the biological sciences, 1939-1949 for physics (again, this time running from the nuclear fission to QED). There are others, of course, and there will be faults with these dates, perhaps--I think that they're pretty good for a start..

I suppose that you could make the case that beginning in 1895 or so that you could say that these great periods of enormous change could begin at the beginning of nearly any year, though I do feel that there are many periods that begin at recognizable dates I think that the existence of these 10-year periods become less abundant as you move to the years before one of the earliest great 10-year periods (1859) simply because it took so long for an idea to go 'viral". Certainly there would be fewer people working in any given field, and communicating even great ideas would've taken far longer in pre-telegraph days. (An interesting question could be how long it took for an idea or thought to be spread thoroughly through a community/nation/world?) There are exceptions of course: the reaction to the invention of the telescope and Galileo''s use of that instrument, and also for the use of the microscope and the work of Robert Hooke being perhaps the most prominent examples.

I like the idea of looking at the unfolding of revolutionary events in 10-year increments. And for the 20th century there would be a solid need to be a geologist of the history of ideas to see how many different levels of change were going on for each revolutionary period.

Comments