JF Ptak Science Books Post 1100 [One in a series on the History of Blank and Missing Things]

Most everything that was once revolutionary, or new, or innovative, comes to the point of being not so to most people, where the thing of marvel and wonder just becomes the thing of interest and then the thing and then, well, sort of no-thing. The great object becomes a simple bridge to something else, whether it is to communicate massive amounts of information instantly or overcoming distance quickly or storing food for long periods of time or shaving nutmeg onto a dinner plate.

Astonishment wears quickly. For example, the long line of vanished astonishment in communications shows how thin wonder becomes over the course of time, as communication is facilitated by a postal delivery system to a ground semaphore to an electric telegraph to the telephone to wireless radio to airmail to television to DARPAnet to email to texting to twitter. The beginning of instantaneous, person-to-person communication is really only 134 years old (with Bell's 1876 invention), and now we're sitting in the middle of the possibility of the most fabulously instantaneous communication bog in the history of humanity, and its brilliant astonishment level has been worn to a dull copper tone. (I don't necessarily mean "fabulous" in a good context, because all of this also presents the greatest assault on concentrated thought that has ever been known, but that's another story.) Things just get taken for granted. (This observation isn't restricted to techno stuff--just ask any old person.)

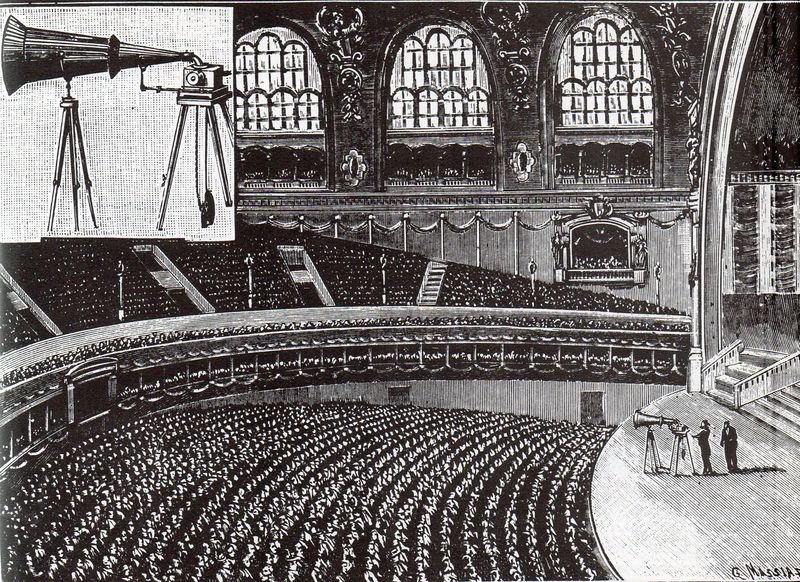

This is an excellent image to remind us of the wonder and fascination of invention--especially for the things that we take for granted, the essentials of modern life. This image from 1897 shows a very large audience gathered in the great Trocadero in Paris to listen to a demonstration of a phonograph. Now the phonograph had already been reliably around since Edison's introduction of his successful machine the year after the invention of the telephone in 1877 (though variations of the instrument had been around since the late 1850's, though that is another story), so the general public was already well-familiar with the concept of captured sound replayed--then why such a big crowd in 1897?

I think the reason for the full house was partially for the fact that it was a home-town event for a national French figure--the machine was being demonstrated by Henri Jules Lioret, an inventor who for about two decades had been tinkering with improvement to the machine. What the Trocadero crowd was listening to was the Lioretograph No. 3, a large, weight-driven phonograph with a big bellow--a machine powerful enough to be heard in a big hall, which was another point of fascination for the attraction of such a large crowd. A third possibility may have been with Lioret himself--perhaps the event was free, perhaps the inventor went out to fill the Trocadero via whatever means possible so that an engraving of the event would appear in newspapers and journals everywhere so that he could sell more machines.

The reason I mos enjoy and wish for though is that the people were simply fascinated with the bright new big machine, filling the famous musical hall with a big sound and doing it without an orchestra, or without one playing player for that matter.

It is also about the wonder of storing and replaying sound.

Loss of astonishment isn't necessarily a complacency--perhaps it is just more of a forgetting, a loss of the stuff that has come before. Maybe it is a function of time, or distance, between newness and necessity.

If you can grow to feel the astonishment felt by this Trocadero audience for the phonograph, or for the astonishment in anything fantastic-if-old, then you get to see the components of today's necessary stuff and see that it has a history and a full geology of an idea. To me, being open to astonishment like this makes you susceptible to wonder, and from wonder comes curiosity, and from curiosity comes everything else worth thinking about.

Notes 1:

Edison celebrates his phonograph in the North American Review

(May 1878) and

then lists what he saw as the readymade faits

acomplis of the invention, the first of which was

weirdly/spectacularly

worded: “1. The captivity of all manner

of sound-waves heretofore designated as fugitive, and their permanent

retention.” Do you hear a soundtrack

with that description? I did. He proceeded

with less fanfare: “2. Their

reproduction with all their original characteristics at will, without

the

presence or consent of the original source, and after the lapse of any

period

of time. 3. The transmission of such captive sounds through the ordinary

channels of

commercial intercourse and trade in material form, for purposes of

communication

or as merchantable goods. 4. Indefinite multiplication and preservation

of

such sounds, without regard to the existence or non-existence of the

original source. 5. The

captivation of sounds, with or without the knowledge or consent of the

source

of their origin.”

Notes 2:

"Clocks Which Will Talk: The Wonderful Possibilities of

Edison's Invention."

"The Phonograph and Its Future." Scientific American Supplement 124 (May 18, 1878): 1973. TAEM 25: 269.

"The Phonograph and Its Future." North American Review 126 (May-June 1878): 527-536. Reprinted widely. TAEM 25: 198-199.

"To the Editor."

"The Phonograph and Its Future." Telegraphic Journal 6 (June 15, 1878): 250. TAEM 25: 265.

"To the Editor."

Comments