JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 704 Blog Bookstore

[on vacation, Tybee Island, Georgia]

This came to mind vacationing with my family; actually, it came while building a sand castle at the lip of the advancing tide, building it up as the water tore it down. That’s the fun of it, even with my six-year old: watching things get made and watching them get unmade, as the getting-unmade part will tell you a whole heck of a lot about the successes and failures of what went into the thing’s making.

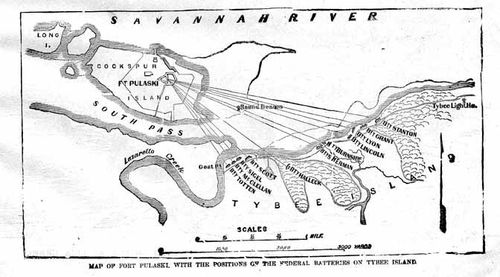

Watching the walls of the fort tumble reminded me of the real-life version of this event, something that happened about two miles away and 147 years ago. For Pulaski was built on the Savannah River to protect the approaches to Savannah and Charleston from the angry reaches of the Spanish and British; in 1862, it was in the hands of the Confederates, and was being used to protect Savannah from the very government that built it.

Even while under the direct commander of General R.E. Lee, thing did not go well for Fort Pulaski and the garrison within. At the end of 1861, the CSA was getting ready for an extended siege of the fort as the Union forces found victories north and south of it. They withdrew their forces from Tybee and threw them into the fort, leaving the Union army a free and insatiable hand to get their hand ready on the other side of the Savannah pass. That said, that’s what pretty much happened: Union forces dragged their cannons through the surf and across the sand, getting them in place around newly-built batteries. This all happened at night so that the Confederates in the fort couldn’t see what was going on, what with all of the evening’s doings camouflaged once the sun came up. (This was still possible at t he time, to keep a secret like this in almost plain view, only a mile away from where the opposing cannons were aimed. The guys in the fort were pretty much cut off from everyone and everything, with only the occasional courier being able to make it through. The garrison was, after all, equipped with enough provisions to last through a siege of 8 months or so.) What happened, finally, was that with the Union cannon in place, the assault began. And instead of a siege lasting for two seasons, it ran about two days. The difference was in the new cannons that were being used the boys in blue—the rifled cannon was brought to play against the massive walls of the fort, and the masonry didn’t stand a chance against the new technology, which as it turns out was first displayed to the world in this battle. And so the ironies: a fort that was built to protect the United States from foreign invaders was used to protect the Confederate States from the United States; and the fort fell not to a sea-based barrage but a land-based one. And after all of this, even though the Pulaski fell in April 1862, Savannah wasn’t captured by the union until December 1864.

An encyclopedia could no doubt be written on nothing but the ironies of bombing. And for another example of this I turn to the French, who can supply more than their share, per capita, pound-for-pound, and percentage of GDP, whatever. No, not the French return to Indochina in 1945 (after having done business with the occupying Japanese forces for the entire war) and their resurgent colonialism as practiced against the Vietnamese, or the heinous practices against the Algerians just prior to that country’s independence: it is their bombing practices in Damascus. Not the Syrian bombings of 1945 (which also included many other places like Aleppo, Hama and etc.) but the French civilian bombings of Damascus in 1925. For it was in that year that the League of Nations found that the French really weren’t bombing and killing civilians indiscriminately when they were doing so; they were, ironically, bombing themselves, and so their actions were not illegal. (It was problematic, identifying “civilians”, as the League didn’t necessarily grant the same sort of “humanness” to all human, finding categories for barbarians and savages. It was acceptable to bomb those later two categories, but not the first.) So the French sought to subdue a rebellion against their oppressive rule in that country, identifying the Muslim population centers in Damascus as probable hotbeds of activities for the “bandits” that were causing them their problems. October 18, 1925 is when this particular outrage occurred; the Syrians protested, and the League considered. And that was about the size of the story for the Syrians, because as it turns out, the French were just maintaining an order that for them was a simple police action; civilians populations could not be bombed in the eyes of international law, if the bombing was being done to a foreign people; since the French were there and occupying the country, they were conducting a police action, and in a sense were merely bombing themselves, loosening them from the barriers of whatever international law could be applied to their actions by the League of Nations.

So there is hardly any shortage of bombing ironies, as we can see here with the null-irony of the French bombing themselves while killing Muslim civilians. When you start looking for irony, sometimes that's all you can see.

Comments