JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 671

"Seeing by telephone or by telegraph may be within the range of the possible. I say that because nothing is impossible until it has been demonstrated so to be. Seeing by either of these instrumentalities, however, is, as I look upon it, so far removed from the field of probability that I should treat any report of this character as an absurdity." T. Edison

I wonder what it was that Thomas Edison dreamt about—I suspect that like most folks he dreamt about himself, though perhaps everyone else in his dreams were him, too. Mr. Edison was a fabulous inventor and thinker—he wasn’t the best person he could’ve been, and even though he had an enormous grasp on the whole of things and ideas about him, he also seemed to grab a little bit more, and a little too much. Which sounds like gluttony.

I’m not so sure why Edison was given to such overstatement on “television”—he just about contradicts his

own rule of thumb in doing so, as though he was going far out of his way to say

something anti-prophetic. Perhaps it was

because “seeing by wire” at this point did not belong to him, like so much

else—which is possible, because Edison

The possibility of interesting dreams swimming around Mr. Edison’s sleeping head was very high, though he may have been one of those poor unfortunates who dream about watching someone else sit in a chair and for hours on end stare at a wall—sounding more like a nightmare than a dream to me.

Good dreams, bad dreams.

History is certainly ankle-deep in literature about the dream, and the

anthropology of dream states must be wide and deep. Dreams don’t show up all that much in the

Bible, though, which seems odd to me—there are 40-odd references to dreams in

the Old Testament, and only nine in the New.

And in the NT five of the dreams come in Matthew (with four of those

referencing the birth of Christ), and another four coming in the Acts of the

Apostles, all of which relate to St.

Paul

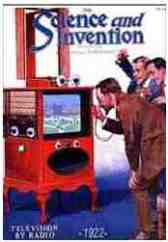

Back to the TV: the truth of the matter is that in spite of the Edisonian condemnation there was real discussions and experiments regarding mechanical (not electronic) television in the late 19th century, and they went a pretty long way towards achieving images by wire. Alexander Bell nearly brought about an image-sending device based on his successful photophone (in 1880), and in that same year George Carey built a primitive sort-of system with light-sensitive cells. Paul Nipkow came the closest of these early pioneers in 1884 with a techy rotating-disk apparatus that successfully achieved an 18-line visual image.

I’m just saying that Mr. Edison had to have been dreaming of

other things that he had more control over.

From where I sit, it seems to me that opportunities for the electrical

transmission of images were quite ripe by the 1890’s. It took another 25 years or so to bring it

all to fulfillment, with a cascade of very successful developments occurring in

1927/8/9. It is a little mysterious to

me why he had such a low opinion of the possibility of television given the electrical

environment of his day.

Here’s

an example of an early effort at the television, appearing in the Letters to Editor in Nature (volume

21, pp 589-589, 22 April 1880): Seeing by Electricity by JOHN PERRY & W. E. AYRTON

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v21/n547/abs/021589a0.html

We hear that a sealed account of an invention for seeing by telegraphy has been deposited by the inventor of the telephone. Whilst we are still quite in ignorance of the nature of this invention, it may be well to intimate that complete means for seeing by telegraphy have been known for some time by scientific men. The following plan has often been discussed by us with our friends, and, no doubt, has suggested itself to others acquainted with the physical discoveries of the last four years. It has not been carried out because of its elaborate nature, and on account of its expensive character, nor should we recommend its being carried out in this form. But if the new American invention, to which reference has been made, should turn out to be some plan of this kind, then this letter may do good in preventing monopoly in an invention which really is the joint property of Willoughby Smith, Sabine, and other scientific men, rather than of a particular man who has had sufficient money and leisure to carry out the idea. The plan, which was suggested to us some three years ago more immediately by a picture in Punch, and governed by Willoughby Smith's experiments, was this transmitter at A consisted of a large surface made up of very small separate squares of selenium. One end of each piece was connected by an insulated wire with the distant place, B, and the other end of each piece connected with the ground, in accordance with the plan commonly employed with telegraph instruments. The object whose image was to be sent by telegraph was illuminated very strongly, and, by means of a lens, a very large image thrown on the surface of the transmitter. Now it is well known that if each little piece of selenium forms part of a circuit in which there is a constant electromotive force, say of a Voltaic battery, the current passing through each piece will depend on its illumination. Hence the strength of electric current in each telegraph line would depend on the illumination of its extremity. Our receiver at the distant place, B, was, in our original plan, a collection of magnetic needles, the position of each of which (as in the ordinary needle telegraph) was controlled by the electric current passing through the particular telegraph wire with which it was connected. Each magnet, by its movement, closed or opened an aperture through which light passed to illuminate the back of a small square of frosted glass. There were, of course, as many of these illuminated squares at B as of selenium squares at A, and it is quite evident that since the illumination of each square depends on the strength of the current in its circuit, and this current depends on the illumination of the selenium at the other end of the wire, the image of a distant object would in this way be transmitted as a mosaic by electricity.”

Some other of the early efforts weren’t so clear on the future applications of sending images by electricity: in this except from Electrician and Mechanic (August, 1906, pages 54-56), Prof. John Andrew’s teletroscope would be able to see what was going on on other planets:

“Professor John E. Andrews of New York

See the man at the other end of the telephone.

Make a phonograph record of all that is said.

Enable one to see what is doing on the planets.”

Comments