JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 683 Blog Bookstore

Part of the History of Dots series

It is interesting to think of the importance of dots in the first revolutionary changes in 500 years in the history of art. Honestly, there wasn’t anything epochal that happened between the re-discovery of perspective (ca. 1330-1400) and the arrival of Impressionism (and just afterwards of non-representational art) in the 1872/3/4-1915 period.

Dots aren’t brought to bear formally in the revolutionary movement until the early 1880’s. Impressionism for all intents and purposes is formed with the Societe Anonyme in 1872 (whose members included Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Sisley, Morisot and eleven others), and perhaps more realistically in 1874 when the Societe exhibited its first salon. (The first show held at the Nadar Studio in Paris in April 1874; a tiny, one month long affair, compared to mammoth exhibitions like the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1867.)

Dots aren’t brought to bear formally in the revolutionary movement until the early 1880’s. Impressionism for all intents and purposes is formed with the Societe Anonyme in 1872 (whose members included Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Sisley, Morisot and eleven others), and perhaps more realistically in 1874 when the Societe exhibited its first salon. (The first show held at the Nadar Studio in Paris in April 1874; a tiny, one month long affair, compared to mammoth exhibitions like the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1867.)

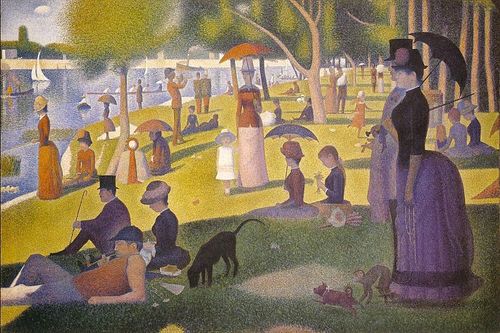

It was Georges Seurat who brought the whole world to the dot experience with his artisitc method of Pointilism, in particular with his magnificent Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte, an enormous work given its composition—dots. The dots replaced the brushstroke, and their placement in relation to their color was an absolutely brilliant innovation, establishing a perfect result for the viewer when examining the work as a whole. (It may well be that the French chemist an designer Michel Chevreul made this discovery a few decades earlier, noticing the effect and changes in color depending on placement and—in his case, with fabric—color in the dyes for his material.)

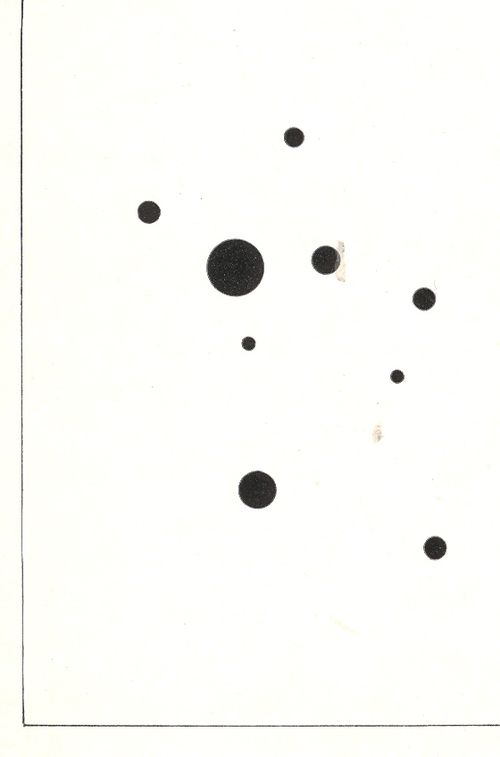

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), the discoverer of nothingness in art and the introduction of the first  non-representational paintings in art history (1913) used his fair share of dots in his exploration of the previously invisible. One good example is his 9 Points in Ascendance (1918), which is nothing but black dots, an impossible composition just two decades prior to its creation.

non-representational paintings in art history (1913) used his fair share of dots in his exploration of the previously invisible. One good example is his 9 Points in Ascendance (1918), which is nothing but black dots, an impossible composition just two decades prior to its creation.

In the middle of this appeared the half-tone illustration, the great liberator of photographic illustration in popular publication. Invented in the late 1870’s by Stephen Henry Horgan and used in the Illustrated London News for the first time in 1881, it made the publication of accurate images much feasible and economical. No longer were readers dependent on the accuracies of artists interpreting photographs or photographed scenes—the photographs themselves were now publishable at little cost and in high quality, vastly increasing the veracity of published reports dependent upon images. This was revolutionary in its own way, democratizing the sharing of images and icons.

And so in just thirty years the lowly dot availed itself of some of the most spectacular achievements in modernism. Of course we can say the same of the line, but this is, after all, a history of dots.

Comments