JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 631 Blog Bookstore

The History of Blank, Empty & Missing Things #44

In America

and Europe for much of the 19th century

books with illustrations received their color by the labor of small-handed

women and older children. For popular,

inexpensive and widely distributed books engravings and woodcuts were often

given their color by an assembly line process:

one person applying the red, another the blue, the third the green, and

so on, until image was completed. This

was a fairly quick process—more than five colors was rare—and once done the

sheets were left to dry before being sent off to be cut, folded, sewn, trimmed

and bound. The colorists wouldn’t really

survive past the 1880’s or so, being replaced by machines and different sorts

of coloring processes—the last book to be published for the mass market being

the 1896 edition of Johnson’s Cyclopedia.

In America

and Europe for much of the 19th century

books with illustrations received their color by the labor of small-handed

women and older children. For popular,

inexpensive and widely distributed books engravings and woodcuts were often

given their color by an assembly line process:

one person applying the red, another the blue, the third the green, and

so on, until image was completed. This

was a fairly quick process—more than five colors was rare—and once done the

sheets were left to dry before being sent off to be cut, folded, sewn, trimmed

and bound. The colorists wouldn’t really

survive past the 1880’s or so, being replaced by machines and different sorts

of coloring processes—the last book to be published for the mass market being

the 1896 edition of Johnson’s Cyclopedia.

This sort of distribution of artistic labor was not new to

the 19th century by any means.

Guilds dictating the strict observance of a painting’s preparation—making

the canvas or preparing the wood, gathering the ingredients for making colors, making

the colors, and so on—stretches back at least 600 years.

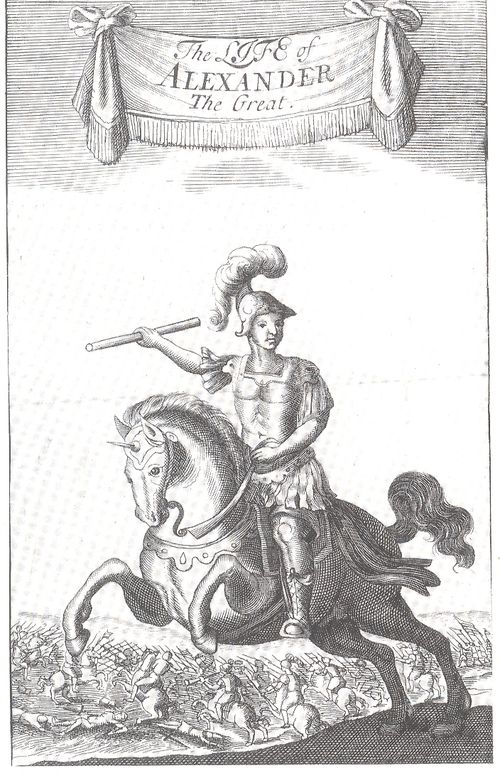

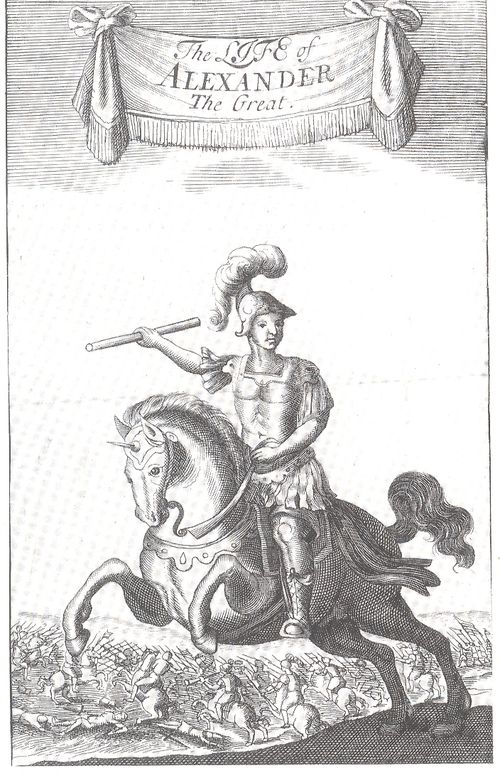

I’m wondering about this because of an illustration that I

found of extremely uneven accomplishment.

It occurs in Quintus Curtius Rufus

The Life of Alexander the Great (“translated by several Gentlemen in the University of Cambridge”) and printed for Gilbert

Cownly in 1687. (I can never let it pass that this is the year that modern

science really began, with the publication of Newton’s Principia…

.) The engraving is the book’s

frontispiece, and shows Alexander on horseback.

Of course there’s no real portrait of Alexander, though his “likeness”

appears on coins from that period. But

the face in the engraving just doesn’t match up to the quality of the rest of

the image. The horse is a little nicer

than standard for the period, and there’s a fair amount of detail in the

background.

The face of the great

Alexander though is pretty bad, drawn in almost as an afterthought even though

he is the subject of the book. Maybe the

engraving’s elements were divided and distributed in the workshop to, say

someone good at horses doing the horse, another good at executing armor doing

that, and so on, until someone realized that no one was there to engrave the

face. And so perhaps it came to pass that Alex received this cheeky/jowly face with a single-muscled skinny neck. (I notice that none of the riders in the background have faces.) Maybe there was only one artist, and they just got tired or figured this face was good enough, and moved on to the next project; perhaps there was just one engraver who was late for dinner and did a too-fast job on the face. And maybe the face was just good enough, no matter who did or or how many people worked on it. I've seen this sort of uneven effort, this missing detail in a detailed work, many times over the years, and I've always wondered what the story was. And I guess I always will.

In America

and Europe

In America

and Europe

Comments