JF Ptak Science Books Post 527

Earlier in this blog I’ve touched on the history of the thought and/or speech balloon (The X-Ray of the Imagination 2: Phrenology, Chinese Hell Scrolls, and the Beauty of the Thought Balloon--Internal Dialog, Demons, Humors, and Picturing the Stuff of Thought...) and I thought for sure that I had included some Renaissance examples of this very expressive additive to the medium, though it seems that I didn’t. Everyone seems to be familiar with the idea, though perhaps it is a minority who know how old the idea is: and it is old, the idea stretching back at least into Medieval times. I know of at least one example from the 12th century: an Evangeilstary from Lower Saxony, executed ca. 1190 (though the influences are Byzantine), where the Gospel texts are introduced with an illuminated page, at least two of which are further illuminated with speech banners. (This was on display in the monumental exhibit called “1200”, shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC in 1970 and pictured in the exhibition catalog.)

The idea must’ve been groundbreaking, though I wonder—as in the case of simultaneous sound-on-film talkies almost instantly replacing the silent film—if there were detractors who raised the issue of the device being a “cheat”, claiming that the art itself should be enough to convey the very thoughts or speech of it subject, which was now displayed in words right on the canvas. (Perhaps there was an implied threat to art itself?) Is this the case with all new or different or revolutionary breakthroughs? Were the minstrels threatened by the new professional theater? Was the production of manuscripts put in jeopardy by movable type presses? Was the Parisian water carrier, the purveyor of the coolest and freshest water threatened by municipal water systems? Radio by television; family cohesion by television; private thought by constant communication devices; symphony by recordings; telegraph by telephone; considered correspondence by email, and so on? (I don’t think there was a “no” response to the above.) It seems as though the response is a time-compressed myoptically-evolutionary response.

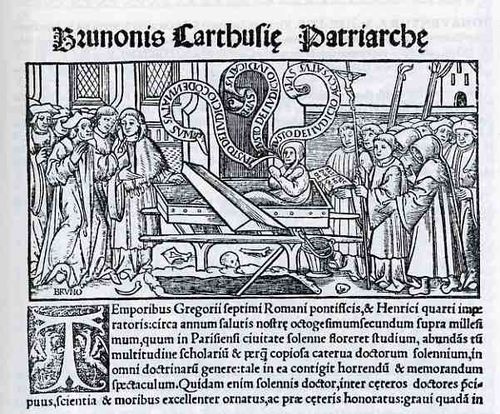

This example, printed in Paris in 1523, is an illustration for the work of Bruno Carthisienni. St. Bruno (who lived ca. 1030 to 1101) born in Cologne and educated in Rheims, was an influential academic with a wide accumulation of knowledge and a wandering spirit he used to establish monasteries. This woodcut is one of the earliest examples of word balloons in a printed book, while the book itself is a monument to typography and illustration. The word balloons in this case are really quite lovely, and seem to almost life their speaker from his casket.

The breadth of your erudition is astounding!

Posted by: Joy | 27 February 2009 at 09:33 PM

Thank you, Joy!

I'm making it all up!

Actually, it would be harder to make it all up, sorta, than to just report on it. On the other hand if it was all made up you couldn't get anything wrong, which would be a relief.

Posted by: John Ptak | 04 March 2009 at 10:35 PM