JF Ptak Science Books LLC Post 332

I've long enjoyed paying attention to stray bits of paper, and books, and directions. (My very first introduction to lovely lovely Ludwig (Wittgenstein) was by picking up his Tractatus from the floor of the library--I had never heard of him before that chance encounter.) And so I've followed these threads for many years, pulling away at whatever was at their end--allot of times the only thing at the end of thread was the end of the thread. On the other hand it has been a good practice and has led me far and wide. This pursuit takes many other forms, but the finding-it-by-chance part can sometimes be exciting and extremely rewarding.

Sometimes it is just satisfying to come to an end. This is the case with this beautiful piece of paper which has come from god-knows-where. Suddenly it was at the bottom of a box, and it didn't even tug at a imitation of a lost memory as to how it got into that box in the first place.

Sometimes it is just satisfying to come to an end. This is the case with this beautiful piece of paper which has come from god-knows-where. Suddenly it was at the bottom of a box, and it didn't even tug at a imitation of a lost memory as to how it got into that box in the first place.

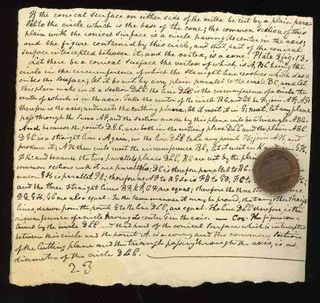

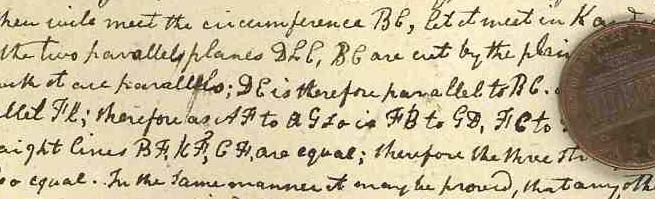

It is very finely written in a strong hand. 30 lines, about 500 words, all on a 4x4.5 inch piece of paper, from about 1775 I reckon. There are plenty of hints about the origins of the text, which I suspected to be a quote; I didn't think it was Euclid, though perhaps an early book on conic sections? Then I looked at the "23" at the bottom and searched in google under "Proposition 23" and Euclid, and then, on only my second try, I had my answer, all in under a minute: Apollonius, the massively important 2nd century BCE geometer and astronomer and namer of the parabola and ellipse and parabola, and whose significance reaches forward 20 centuries. Now having the answer and doing something with it are two different things, and in this case there was no where else for me to go. Sometimes just finding out what something *is* is enough.

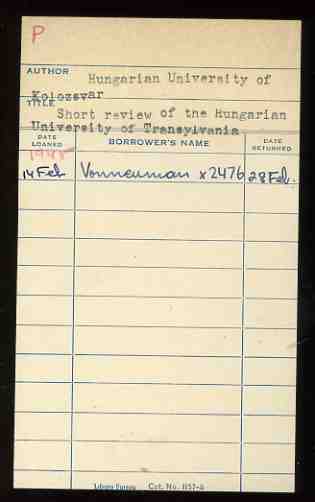

Earlier this week I breezed through a pamphlet called A Short History of the Hungarian University of Transylvania (1943), published by the Hungarian University of Koloszvar, a thin, elegant and erudite work. It had been in the library of some offices of the old OSS (Office of Strategic Services), the forerunner to the CIA). In the back was the borrower's card, with a borrower's name on it. Generally when I find this stuff the card is almost always blank--but in this case, the little slip bore an important name: "vonNeuman" it said. The pamphlet was borrowed 14 Feb and returned 28 Feb, 1945. It had von Neuman's phone number on it too. My initial reaction was fantastic--this was Johnny von Neumann's name. He defined "secret" work for the government during the war; he was Hungarian; I think he was with the OSS. Von Neumann was probably the most fantastic mind of the century. And here he was, in the back of this little pamphlet.

And then it struck me.

This was von Neuman, not von Neumann.

I was missing an "n". I wanted so badly for it to be there, but it just wasn't going to happen. In the small world category, I believe that this is Hans J. Neuman, who worked at the OSS during the war and who went on to a distinguished career in computer science (and who made significant contributions to the creation of the first computer at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania). Some 20 years ago I appraised the library part of his estate.

Comments